All the exotic hadrons that have been observed so far decay rapidly via the strong interaction. The ccūd̄ tetraquark (Tcc+ ) just discovered by the LHCb collaboration is no exception. However, it is the longest-lived state yet, and reinforces expectations that its beautiful cousin, bbūd , will be stable with respect to the strong interaction when its peak emerges in future data.

“We have discovered a ccūd tetraquark with a mass just below the D*+D0 threshold which, according to most models, indicates that it is a bound state,” says LHCb analyst Ivan Polyakov (Syracuse University). “It still decays to D mesons via the strong interaction, but much less intensively than other exotic hadrons.”

Most of the exotic hadronic states discovered in the past 20 years or so are cc̄qq̄ tetraquarks or cc̄qqq pentaquarks, where q represents an up, down or strange quark. A year ago LHCb also discovered a hidden-double-charm cc̄cc̄ tetraquark, X(6900), and two open-charm csūd tetraquarks, X0(2900) and X1(2900). The new ccūd state, presented today at the European Physical Society conference on high-energy physics to have been observed with a significance substantially in excess of five standard deviations, is the first exotic hadronic state with so-called double open heavy flavour — in this case, two charm quarks unaccompanied by antiparticles of the same flavour.

Astoundingly, its observation by LHCb reveals that it is a mere 270 keV below the threshold

Prime Candidate

Tetraquark states with two heavy quarks and two light antiquarks have been the prime candidates for stable exotic hadronic states since the 1980s. LHCb’s discovery, four years ago, of the Ξcc++ (ccu) baryon allowed QCD phenomenologists to firmly predict the existence of a stable bbūd tetraquark, however the stability of a potential ccūd state remained unclear. Predictions of the mass of the ccūd state varied substantially, from 250 MeV below to 200 MeV above the D*+D0 mass threshold, say the team. Astoundingly, its observation by LHCb reveals that it is a mere 273 ± 61 keV below the threshold — a bound state, then, but with the threshold for strong decays to D*+D0 lying within the observed resonance’s narrow width of 410 ± 165 keV, prescribed by the uncertainty principle. The Tcc+ tetraquark can therefore decay via the strong interaction, but strikingly slowly. By contrast, most exotic hadronic states have widths from tens to several hundreds of MeV.

“Such closeness to the threshold is not very common in heavy-hadron spectroscopy,” says analyst Vanya Belyaev (Kurchatov Institute/ITEP). “Until now, the only similar closeness was observed for the enigmatic χc1(3872) state, whose mass coincides with the D*0D0 threshold with a precision of about 120 keV.” As it is wider, however, it is not yet known whether the χc1(3872) is below or above threshold.

I am fascinated by the idea that a strong coupling to a decay channel might attract the bare mass of the hadron

Mikhail Mikhasenko

“The surprising proximity of Tcc+ and χc1(3872) to the D*D thresholds must have deep reasoning,” adds analyst Mikhail Mikhasenko (ORIGINS, Munich). “I am fascinated by the idea that, roughly speaking, a strong coupling to a decay channel might attract the bare mass of the hadron. Tremendous progress in lattice QCD over the past 10 years gives us hope that we will discover the answer soon.”

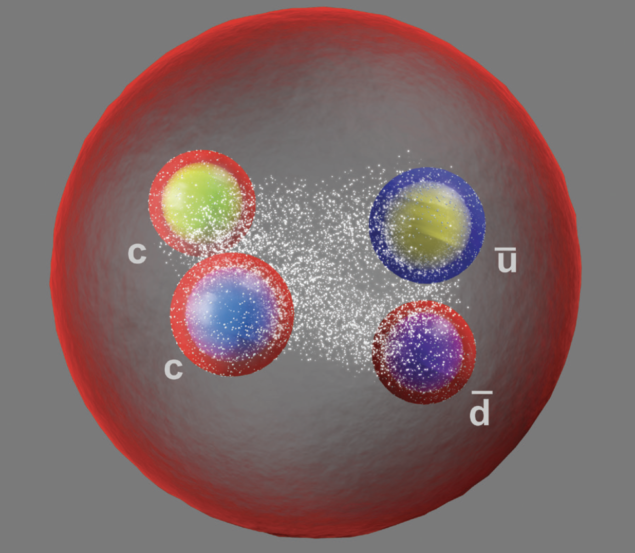

The cause of this attraction, says Mikhasenko, could be linked to a “quantum admixture” of two models that vie to explain the structure of the new tetraquark: it could be a D*+ and a D0 meson, bound by the exchange of colourneutral objects such as light mesons, or a colour-charged cc “diquark” tightly bound via gluon exchange to up and down antiquarks (see “Jumbled together” figure). Diquarks are a frequently employed mathematical construct in low-energy quantum chromodynamics (QCD): if two heavy quarks are sufficiently close together, QCD becomes perturbative, and they may be shown to attract each other and exhibit effective anticolour charge. For example, a red-green cc diquark would have a wavefunction similar to an anti-blue anti-quark, and could pair up with a blue quark to form a baryon — or, hypothetically, a blue anti-diquark, to form a colour-neutral tetraquark.

“The question is if the D and D* are more or less separated, jumbled together to such a degree that all quarks are intertwined in a compact object, or something in between,” says Polyakov. “The first scenario resembles a relatively large ~4 fm deuteron, whereas the second can be compared to a relatively compact ~2 fm alpha particle.”

The new Tcc+ tetraquark is an enticing target for further study. Its narrow decay into a D0D0π+ final state — the virtual D*+ decays promptly into D0π+ — includes no particles that are difficult to detect, leading to a better precision on its mass than for existing measurements of charmed baryons. This, in turn, can provide a stringent test for existing theoretical models and could potentially probe previously unreachable QCD effects, says the team. And, if detected, its beautiful cousin would be an even bigger boon. “Observing a tightly bound exotic hadron that would be stable with respect to the strong interaction would be a cornerstone in understanding QCD at the scale of hadrons,” says Polyakov. “The bbūd , which is believed to satisfy this requirement, is produced rarely and is out of reach of the current luminosity of the LHC. However, it may become accessible in LHC Run 3 or at the High-Luminosity LHC.” In the meantime, there is no shortage of work in hadron spectroscopy, jokes Belyaev. “We definitely have more peaks than researchers!”