In the history of elementary particle physics, 1964 was truly an annus mirabilis. Not only did the quark hypothesis emerge – independently from two theorists half a world apart – but a multiplicity of theorists came up with the idea of spontaneous symmetry breaking as an attractive method to generate elementary particle masses. And two pivotal experiments that year began to alter the way astronomers, cosmologists and physicists think about the universe.

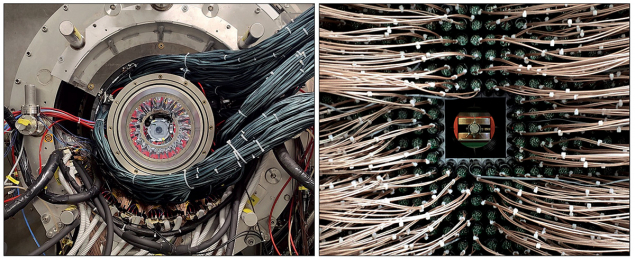

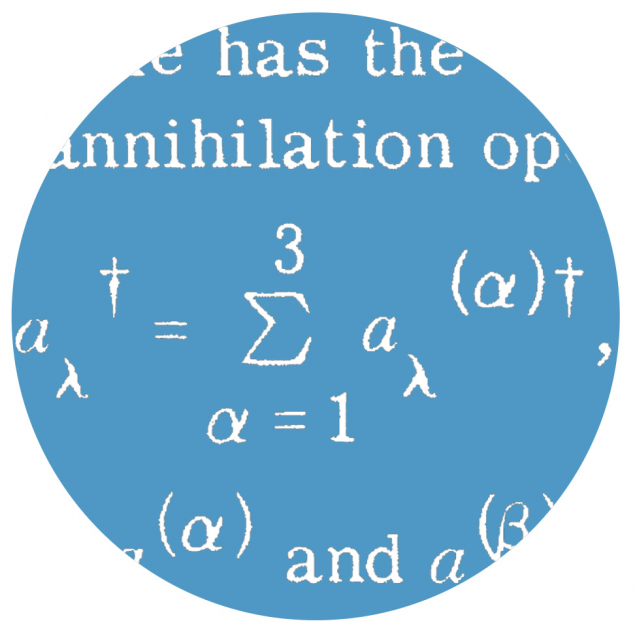

Shown on the left is a timeline of the key 1964 milestones; discoveries that laid the groundwork for the Standard Model of particle physics and continue to be actively studied and refined today (images: N Eskandari, A Epshtein).

Some of the insights published in 1964 were first conceived in 1963. Caltech theorist Murray Gell-Mann had been ruminating about quarks ever since a March 1963 luncheon discussion with Robert Serber at Columbia University. Serber was exploring the possibility of a triplet of fundamental particles that in various combinations could account for mesons and baryons in Gell-Mann’s SU(3) symmetry scheme, dubbed “the Eightfold Way”. But Gell-Mann summarily dismissed his suggestion, showing him on a napkin how any such fundaments would have to have fractional charges of –2/3 or 1/3 the charge on an electron, which seemed absurd.

From the ridiculous to the sublime

Still, he realised, such ridiculous entities might be allowable if they somehow never materialised outside of the hadrons. For much of the year, Gell-Mann toyed with the idea in his musings, calling such hypothetical entities by the nonsense word “quorks”, until he encountered the famous line in Finnegans Wake by James Joyce, “Three quarks for Muster Mark.” He even discussed it with his old MIT thesis adviser, then CERN Director-General Victor Weisskopf, who chided him not to waste their time talking about such nonsense on an international phone call.

In late 1963, Gell-Mann finally wrote the quark idea up for publication and sent his paper to the newer European journal Physics Letters rather than the (then) more prestigious Physical Review Letters, in part because he thought it would be rejected there. “A schematic model of baryons and mesons”, published on 1 February 1964, is brief and to the point. After a few preliminary remarks, he noted that “a simpler, more elegant scheme can be constructed if we allow non-integral values for the charges … We then refer to the members u(2/3), d(–1/3) and s(–1/3) of the triplet as ‘quarks’.” But toward the end, he hedged his bets, warning readers not to take the existence of these quarks too seriously: “A search for stable quarks of charge +2/3 or –1/3 … at the highest-energy accelerators would help to reassure us of the non-existence of real quarks.”

As often happens in the history of science, the idea of quarks had another, independent genesis – at CERN in 1964. George Zweig, a CERN postdoc who had recently been a Caltech graduate student with Richard Feynman and Gell-Mann, was wondering why the φ meson lived so long before decaying into a pair of K mesons. A subtle conservation law must be at work, he figured, which led him to consider a constituent model of the hadrons. If the φ were somehow composed of two more fundamental entities, one with strangeness +1 and the other with –1, then its great preference for kaon decays over other, energetically more favourable possibilities, could be explained. These two strange constituents would find it difficult to “eat one another,” as he later put it, so two individual, strange kaons would be required to carry each of them away.

Late in the fall of 1963, Zweig discovered that he could reproduce the meson and baryon octets of the Eightfold Way from such constituents if they carried fractional charges of 2/3 and –1/3. Although he at first thought this possibility artificial, it solved a lot of other problems, and he began working feverishly on the idea, day and night. He wrote up his theory for publication, calling his fractionally charged particles “aces” – in part because he figured there would be four of them. Mesons, built from pairs of these aces, formed the “deuces” and baryons the “treys” in his deck of cards. His theory first appeared as a long CERN report in mid-January 1964, just as Gell-Mann’s quark paper was awaiting publication at Physics Letters.

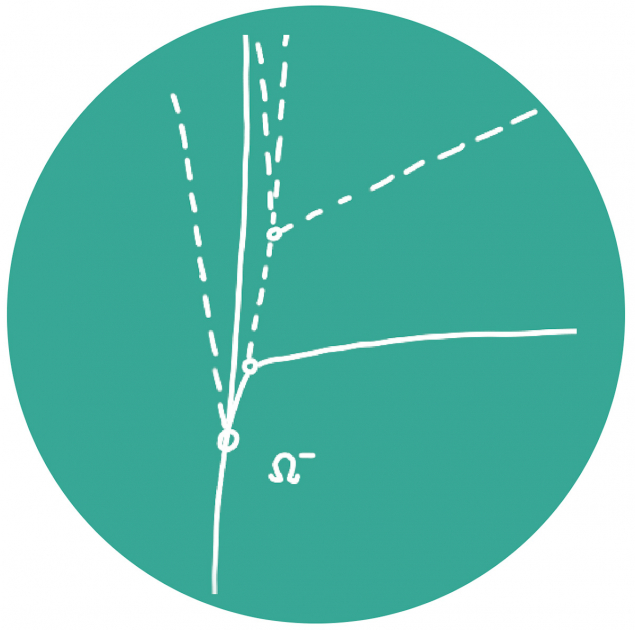

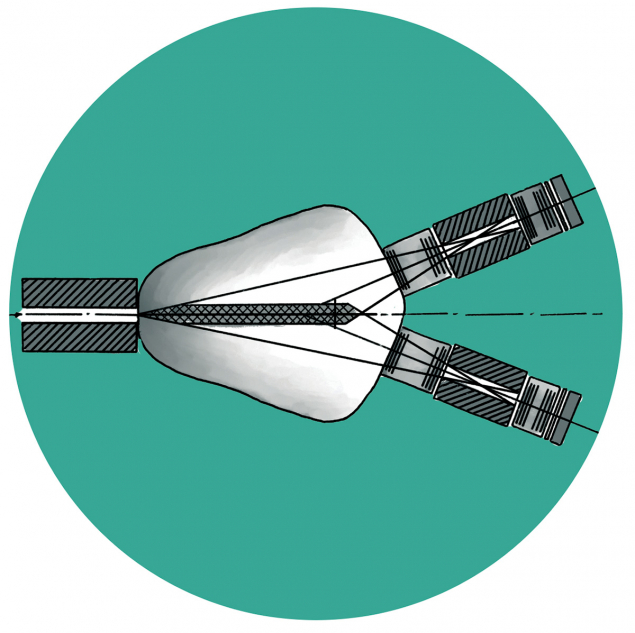

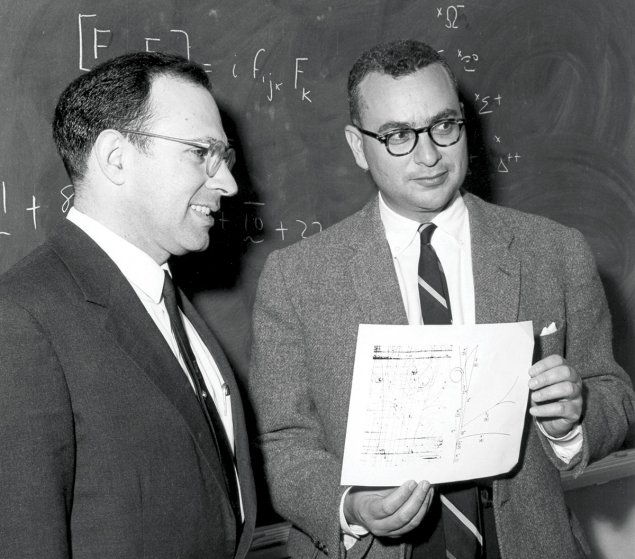

As chance would have it, there was an intensive activity going on in parallel that January – an experimental search for the Ω– baryon that Gell-Mann had predicted just six months earlier at a Geneva particle-physics conference. With negative charge and a mass almost twice that of the proton, it had to have strangeness –3 and would sit atop a 10-fold decuplet of heavy baryons predicted in his Eightfold Way. Brookhaven experimenter Nick Samios was eagerly seeking evidence of this very strange particle in the initial run of the 80 inch bubble chamber that he and colleagues had spent years planning and building. On 31 January 1964, he finally found a bubble-chamber photograph with just the right signatures. It might be the “gold-plated event” that could prove the existence of the Ω– baryon.

After more detailed tests to make sure of this conclusion, the Brookhaven team delivered a paper with the unassuming title “Observation of a hyperon with strangeness minus three” to Physical Review Letters. With 33 authors, it reported only one event. But with that singular event, any remaining doubt about SU(3) symmetry and Gell-Mann’s Eightfold Way evaporated.

A fourth quark for Muster Mark?

Later in spring 1964, James Bjorken and Sheldon Glashow crossed paths in Copenhagen, on leave from Harvard and Stanford, working at Niels Bohr’s Institute for Theoretical Physics. Seeking to establish lepton–hadron symmetry, they needed a fourth quark because a fourth lepton – the muon neutrino – had been discovered in 1962 at Brookhaven. Bjorken and Glashow were early adherents of the idea that hadrons were made of quarks, but based their arguments on SU(4) symmetry rather than SU(3). “We called the new quark flavour ‘charm,’ completing two weak doublets of quarks to match two weak doublets of leptons, and establishing lepton–quark symmetry, which holds to this day,” recalled Glashow (CERN Courier January/February 2025 p35). Their Physics Letters article appeared that summer, but it took another decade before solid evidence for charm turned up in the famous J/ψ discovery at Brookhaven and SLAC. The charm quark they had predicted in 1964 was the central player in the so-called November Revolution a decade later that led to widespread acceptance of the Standard Model of particle physics.

In the same year, Oscar Greenberg at the University of Maryland was wrestling with the difficult problem of how to confine three supposedly identical quarks within a volume hardly larger than a proton. According to the sacrosanct Pauli exclusion principle, identical spin–1/2 fermions could never occupy the exact same quantum state. So how, for example, could one ever cram three strange quarks inside an Ω– baryon?

One possible solution, Greenberg realised, was that quarks carry a new physical property that distinguished them from one another so they were not in fact identical. Instead of a single quark triplet, that is, there could be three distinct triplets of what he dubbed “paraquarks”, publishing his ideas in November 1964, and capping an extraordinary year of insights into hadrons. We now recognise his insight as anticipating the existence of “coloured” quarks, where colour is the source of the relentless QCD force binding them within mesons and baryons.

The origin of mass

Although it took more than a decade for experiments to verify them, these insights unravelled the nature of hadrons, revealing a new family of fermions and hinting at the nature of the strong force. Yet they were not necessarily the most important ideas developed in particle physics in 1964. During that summer, three theorists – Robert Brout, François Englert and Peter Higgs – formulated an innovative technique to generate particle masses using spontaneous symmetry breaking of non-Abelian Yang–Mills gauge theories – a class of field theories that would later describe the electroweak and strong forces in the Standard Model.

Inspired by successful theories of superconductivity, symmetry-breaking ideas had been percolating among those few still working on quantum field theory, then in deep decline in particle physics, but they foundered whenever masses were introduced “by hand” into the theories. Or, as Yoichiro Nambu and Peter Goldstone realised in the early 1960s, massless bosons appeared in the theories that did not correspond to anything observed in experiments.

If they existed, the W (and later, Z) bosons carrying the short-range weak force had to be extremely massive (as is now well known). Brout and Englert – and independently Higgs – found they could generate the masses of such vector bosons if the gauge symmetry governing their behaviour was instead spontaneously broken, preserving the underlying symmetry while allowing for distinctive, asymmetric particle states. In solid-state physics, for example, magnetic domains will spontaneously align along a single direction, breaking the underlying symmetry of the electromagnetic field. Brout and Englert published their solution in June 1964, while Higgs followed suit a month later (after his paper was rejected by Physics Letters). Higgs subsequently showed that this symmetry breaking required a scalar boson to exist that was soon named after him. Dubbed the “Higgs mechanism,” this mass-generating process became a crucial feature of the unification of the weak and electromagnetic forces a few years later by Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam. And after their electroweak theory was shown in 1971 to be renormalisable, and hence calculable, the theoretical floodgates opened wide, leading to today’s dominant Standard Model paradigm.

Surprise, surprise!

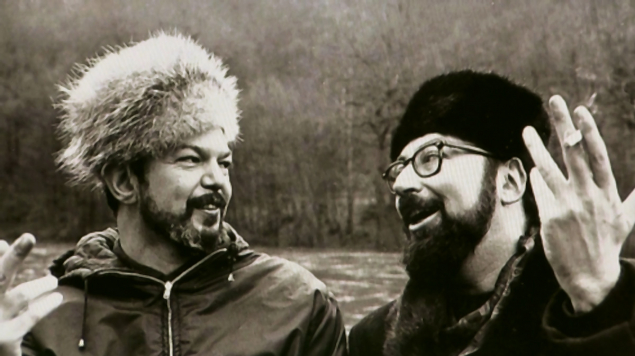

Besides the quark model and the Higgs mechanism, 1964 witnessed two surprising discoveries that would light up almost any other year in the history of science. That summer saw the publication of an epochal experiment leading to the discovery of CP violation in the decays of long-lived neutral mesons. Led by Princeton physicists Jim Cronin and Val Fitch, their Brookhaven experiment had discerned a small but non-negligible fraction – 0.2% – of two-body decays into a pair of pions, instead of into the dominant CP-conserving three-body decays. For months, the group wrestled with trying to understand this surprising result before publishing it that July in Physical Review Letters.

It took almost another decade before Japanese theorists Makoto Kobayashi and Toshihide Maskawa proved that such a small amount of CP violation was the natural result of the Standard Model if there were three quark-lepton families instead of the two then known to exist. Whether this phenomenon has any causal relation to the dominance of matter in the universe is still up for grabs decades later. “Indeed, it is almost certain that the CP violation observed in the K-meson system is not directly responsible for the matter dominance of the universe,” wrote Cronin in the early 1990s, “but one would wish that it is related to whatever the mechanism was that created [this] matter dominance.”

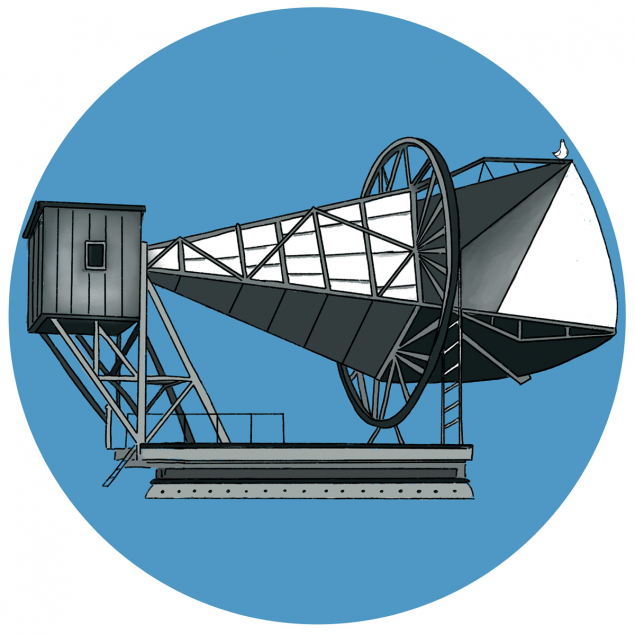

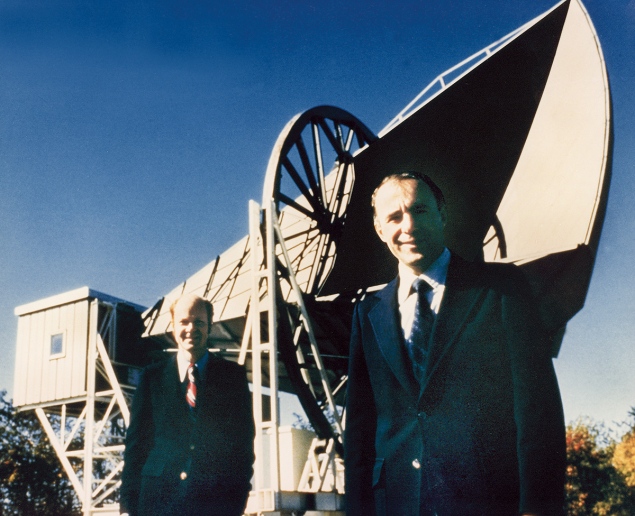

Another epochal 1964 observation was not published until 1965, but it deserves mention here because of its tremendous significance for the subsequent marriage of particle physics and cosmology. That summer, Arno Penzias and Robert W Wilson of Bell Telephone Labs were in the process of converting a large microwave antenna in Holmdel, NJ, for use in radio astronomy. Shaped like a giant alpenhorn lying on its side, the device had been developed for early satellite communications. But the microwave signals that it was receiving included a faint, persistent “hiss” no matter the direction in which the horn was pointed; they at first interpreted the hiss as background noise – possibly due to some smelly pigeon droppings that had accumulated inside, which they removed. Still it persisted. Penzias and Wilson were at a complete loss to explain it.

Cosmological consequences

It so happened that a Princeton group led by Robert Dicke and James Peebles was just then building a radiometer to search for the uniform microwave radiation that should suffuse the universe had it begun in a colossal fireball, as a few cosmologists had been arguing for decades. In the spring of 1965, Penzias read a preprint of a paper by Peebles on the subject and called Dicke to suggest he come to Holmdel to view their results. After arriving and realising they had been scooped, the Princeton physicists soon confirmed the Bell Labs results using their own rooftop radiometer.

Besides the quark model and the Higgs mechanism, 1964 witnessed two surprising discoveries that would light up almost any other year in the history

of science

The results were published as back-to-back letters in the Astrophysical Journal on 7 May 1965. The Princeton group wrote extensively about the cosmological consequences of the discovery, while Penzias and Wilson submitted just a brief, dry description of their work, “A measurement of excess antenna temperature at 4080 Mc/s” – ruling out other possible interpretations of the uniform signal corresponding to the radiation expected from a 3.5 K blackbody.

Subsequent measurements at many other frequencies have established that this is indeed the cosmic background radiation expected from the Big Bang birth of the universe, confirming that it had in fact occurred. That was an incredibly brief, hot, dense phase of its existence, which has prodded many particle physicists to take up the study of its evolution and remnants. This discovery of the cosmic background radiation therefore serves as a fitting capstone on what was truly a pivotal year for particle physics.