This time last year, it became clear at the Neutrino 2004 conference that results from experiments on solar and atmospheric neutrinos are converging with those from accelerators (in particular, KEK to Kamioka, or K2K, in Japan) and reactors (as in KamLAND, also in Japan) in pointing to a definite neutrino deficit due to an oscillation mechanism. However, further understanding will require new experiments, aimed at making precision measurements of all the parameters of the Pontecorvo-Maki-Nakagawa-Sakata (PMNS or MNSP) leptonic mixing matrix that describes the oscillation mechanism.

The major challenge will be to detect a potential violation of charge-parity (CP) invariance in the leptonic sector, which might in turn make a crucial contribution to explaining the matter-antimatter asymmetry in our universe. Such experiments will require the use of huge “mega-detectors”.

The first generation of large-volume detectors was initially designed to measure proton decay. By pushing up the limits on the lifetime of the proton by two orders of magnitude, these experiments made it possible to exclude a minimal SU5 theory as the theory for grand unification. A new, second generation of experiments would make it possible to increase the sensitivity to the proton lifetime by two further orders of magnitude, and check the validity of a significant number of supersymmetry theories. The kind of detector required would also be well suited to the study of those major events in the history of the universe that we know as supernovae.

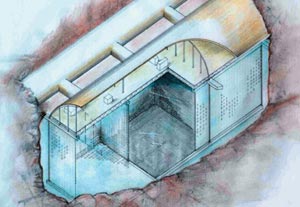

It is therefore quite appropriate for the same conference to address the detection of neutrinos, the measurement of the proton lifetime and issues relating to cosmology, as in this year’s meeting on the Next Generation of Nucleon Decay and Neutrino Detectors (NNN), held near the Laboratoire Souterrain de Modane (LSM). Originally the site of a detector to study proton instability, the LSM is now a potential site for hosting a mega-detector, capable of receiving a low-energy neutrino beam from CERN, 130 km away. Thus, on 7-9 April 2005, around 100 participants, mainly from Europe, Japan and the US, came together for a conference at the CNRS’s Paul Langevin Centre at nearby Aussois organized by IN2P3 (CNRS) and Dapnia (DSM/CEA), with financial support from photomultiplier manufacturers Hamamatsu, Photonis and Electron Tubes Ltd (ETL).

The first day of the meeting was dedicated to theory, physics motivations and future experimental projects to be pursued at underground sites. John Ellis from CERN opened the conference with a striking plea in favour of this type of physics; he insisted that it complemented collider physics, and emphasized the potential discoveries to be made with a mega-detector.

Specialists in the field explained that proton decay, which has not yet been discovered, is still the key to grand unified theories. Recalling that the detectors built to measure the proton lifetime had made it possible to detect neutrinos from supernovae for the first time, subsequent presentations addressed potential approaches to supernova physics, about which little is known, through the high-statistics detection of the neutrinos from these stellar explosions. As Gianluigi Fogli of Bari and Sin’ichiro Ando of Tokyo explained, such a detector would make it possible to extend to neighbouring galaxies the study of these major events in the evolution of the universe, be they in the future or in the distant past.

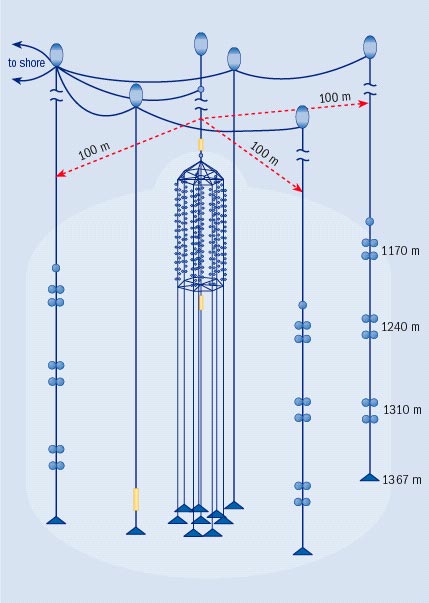

The afternoon sessions moved on to consider future detectors that could be sited at locations where the detection of neutrino beams, at some distance from an accelerator, could be combined with the observation of proton decay and astrophysical neutrinos. These presentations took stock of the progress of large-scale detector projects in the US, Asia and Europe.

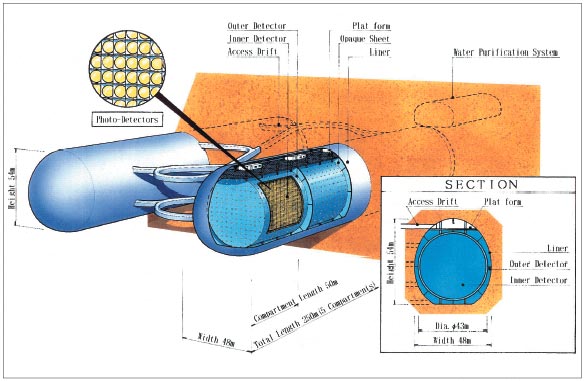

On the face of it, the most accessible technology (the best known and simplest to implement) uses the Cherenkov effect in water, as proposed for the Hyper-Kamiokande project in Japan and the Underground Nucleon Decay and Neutrino Observatory (UNO) project in the US. The most ambitious technology is without doubt that for a large liquid-argon time-projection chamber (100 kt), a bold derivative of the ICARUS detector currently under preparation in the Gran Sasso Laboratory. Further promising alternatives look to organic scintillating liquids, as in the Low Energy Neutrino Astronomy project (LENA), and even a magnetized iron calorimeter as in the India-based Neutrino Observatory (INO).

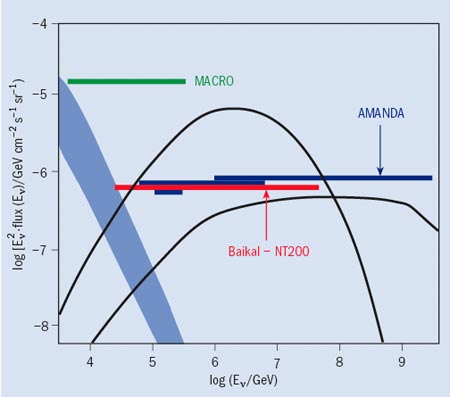

Precision measurements of the θ13 mixing angle in the PMNS matrix, with a value that conditions the possibility of obtaining a measurement of CP violation, require high-intensity neutrino beams. The following day, the conference heard presentations on the worldwide status of experiments using a beam to verify the results obtained with solar or atmospheric neutrinos. For Japan – in addition to the K2K experiment, which has already successfully launched such a programme – the opportunities offered by a successor, Tokai to Kamioka (T2K), at the new Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex (J-PARC) were reviewed. For the US, following the report of the first results after the successful launch of the Main Injector Neutrino Oscillation Search (MINOS), presentations highlighted the opportunities for measuring θ13 at Fermilab with experiments using off-axis beams to the Soudan mine, as well as the very-long-distance projects from Brookhaven towards several prospective sites.

Moving on to CERN, and Europe more generally, the opportunities for beams to the Gran Sasso Laboratory, which hosts the OPERA and ICARUS experiments, were defined. A series of contributions also demonstrated the validity and physics potential of longer-term projects that are likely to be of direct interest to the CERN community. These are based on the superbeams and neutrino beta-beams produced by the beta-decays of certain light nuclei, such as helium or neon, and even by the decay of dysprosium, which has been met with enthusiasm since the recent discovery of this possibility.

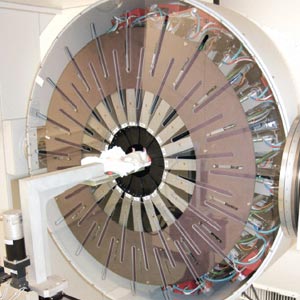

The afternoon session of the second day was mainly devoted to the complex but encouraging R&D efforts in fields as varied as the study of the different physics and instrumental backgrounds, and photo detection. In particular, the presence and support from principal actors in the field of photomultiplier manufacture led to a series of promising technical presentations, in addition to those by physicists on the efforts underway in laboratories in the field of photo detection. The clear objective is to build photomultipliers able to cover large surface areas. The synergies with other fields of research, such as geophysics and rock mechanics, were also underlined.

On one hand, the conference sought to follow in the footsteps of its predecessors; on the other it aimed to ensure that such meetings were held on a more regular basis, and to rationalize their agendas. With this in mind, the day concluded with a round-table discussion, where the participants included Alain Blondel (Geneva), Jacques Bouchez (Saclay), Gianluigi Fogli (Bari), Chang Kee Jung (Stony Brook), Kenzo Nakamura (Tsukuba), André Rubbia (Zurich) and Bernard Sadoulet (Berkeley). It was moderated by Michel Spiro (IN2P3), who proposed making the NNN an annual event and improving coordination of the community’s R&D efforts. This would be done by setting up an inter-regional committee, consisting of several members for each region (Europe, North America, Japan and so on), with a view to validating the construction of a very large detector in around 2010. The committee would also maintain contacts with the steering group for ECFA Studies of a European Neutrino Factory and Future Neutrino Beams, which is chaired by Blondel.

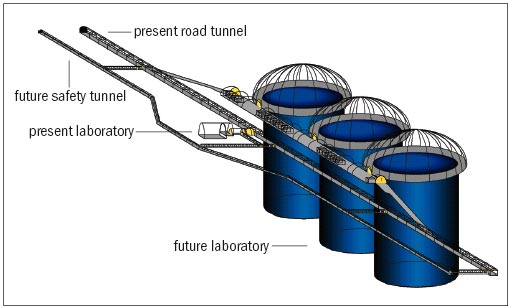

On the last day, before the organized visit to the LSM, an entire session was devoted to a series of presentations from Japan, the US and France. Taking an engineering point of view, this session examined the potential caverns for housing a megatonne detector. Several possible sites are being considered in the US, and the Japanese are presenting the results of their studies for the Kamioka sites. In Europe, the Fréjus site on the Franco-Italian border could host a megatonne detector, so long as the preliminary studies, which have already begun, yield positive results.

The various presentations given throughout the NNN05 conference clearly highlighted the possible areas for exchanges between the different regions and communities, which until now have tended to pursue distinct paths. The next NNN conference will be held in the US in 2006, and the following meeting has already been scheduled to take place on 2 October 2007 at Hamamatsu in Japan, the Japanese “shrine” for photomultipliers.