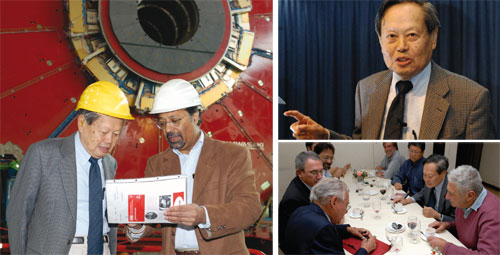

Chen Ning Yang first came to CERN in 1957, the year he shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Tsung-Dao Lee for their proposal that the weak interaction violates parity symmetry – at a fundamental level, the mirror symmetry between left and right is broken. Almost 50 years later, Yang was again at CERN speaking to a packed auditorium about his thoughts on the important themes in physics over the second half of the 20th century. He can do so with authority: he not only knew great physicists such as Wolfgang Pauli and Paul Dirac, but he has also made many fundamental contributions to physics from the 1950s onwards.

When Yang arrived at CERN in 1957 the theory group was housed in a hut at Cointrin by the villa visible still behind fences surrounding the airport, and he recalls meeting people such as Jack Steinberger, Oreste Piccioni and Bruno Ferretti. But the visit also had a personal significance for Yang, who had lived in the US for 12 years, having left his native China in 1945. In the US he had gained his PhD, working under Edward Teller at Chicago University, and by 1957 he was married with a six-year-old son. It was a time of difficult relations between China and the US, with no possibility for Yang and his new family to meet with his parents in either country. However, the trip to Geneva offered Yang the opportunity to arrange for his father to come from China for a six-week visit and meet his wife and son. This happy experience was repeated on further visits to CERN in 1960 and 1962.

Throughout his long career Yang made many contributions to physics, achieving two of his best-known contributions to particle physics – Yang–Mills theory and parity violation – by the time he was 34. Yang says that he was fortunate to come into physics when the concept of symmetry was beginning to be appreciated.

In the 1920s people did not like the concept of symmetry, as they were sceptical of its new mathematics of groups – there were those who even talked of “the group pest”. But in the 1930s physicists began to realize that symmetry was necessary to describe atomic physics; in particular, symmetry groups explained the structure of the Periodic Table. By the 1940s its application had extended to nuclear and particle physics.

Yang worked on group theory for his PhD thesis under Teller, and this firmly anchored his interest in groups and the emerging field of symmetry in particle physics. He now reflects: “When young, the best thing that you can do is to launch yourself into a field that is just beginning.” This is exactly what Yang did.

Yang–Mills theory

By 1954 he had written with Robert Mills what he still regards as his most important paper, laying out the basic principles of what has become known as Yang–Mills theory. The theory is now a cornerstone of the Standard Model of particle physics, but at the time it did not agree with experiment. “We couldn’t escape the question of the mass of the spin-1 particles that come out of it,” recalls Yang, “although we did discuss it at the end of the paper and implied that there may be other reasons for the mass not being zero.” So why did they write the paper? Yang says that he appreciated the beauty of the structure and believed that it should be published. Samuel Goudsmit, who together with George Uhlenbeck had discovered the electron’s spin, was the editor and speedily published the paper.

On the subject of his Nobel prize-winning work with Lee, Yang says he was very proud of the paper on parity violation. “It caused a great sensation because of its ‘across the board’ character,” he recalls. “It was relevant to nuclear physics as well as high-energy physics. There were hundreds of experiments in the following two years.” The paper was published on 1 October 1956, and on 27 December C S Wu and her colleagues had the results that demonstrated that the parity is violated in weak decays. Yang says that Wu contributed more than just her technical expertise: “She did not believe the experiment would be so exciting, but believed that if an important principle had not been tested, it should be. No-one else wanted to do it!”

Since 1957 Yang has visited CERN many times and has seen the latest accelerator installations, each larger and more complex than the previous generation. This time he was taken to see preparations for ATLAS and CMS, the huge general-purpose detectors being built for the LHC. Yang says that seeing these installations is “very educational for a theorist who doesn’t tangle with these complex detectors and the engineers who are putting it all together”. He was “more than impressed” he says: “It is quite unbelievable. My only regret is that I may not be around to see the results.”

The changing face of particle physics

As the detectors become larger and more complex they are also being built and run by physicists and engineers who are collaborating on a very large scale. How particle physics is done has changed a great deal in the 50 years since Yang’s first visit to CERN. “Now group members are named by countries,” Yang says. “We have progressed from teams of colleagues in an institute, to several institutes, to several countries.” At CMS in particular he was impressed by all the young people from different countries who were participating in data-taking tests during his visit.

Looking to the future, Yang believes that astronomy is going to be an exciting field because so many peculiar aspects not yet understood will provide many opportunities for exploration. More fundamentally, he thinks that while the nature of physics has changed in the 21st century it will continue to thrive, resulting in important contributions to science.

So what of high-energy physics? Is it coming to an end? Yang believes that the type of particle physics studied over the past 50 years is not likely to continue for two reasons: one external and one internal. He points out that his generation was fortunate in that they launched into the unknown where there was a great deal to be discovered. Now, he says, we have reached marvellous collaboration efforts with the LHC, but there are limits to what governments will support. This is the external factor: funding will limit expansion unless there is some bright new idea. “We need to reduce the budget by a factor of 10,” he says.

As for the internal factor, he sees that the subject faces more difficult mathematical structures. He notes that field theory today has become highly nonlinear and is very difficult compared with what was thought to be difficult in the 1940s.

In the meantime, what does he think will be the most important discovery at the LHC? “Everybody is focusing on the Higgs and most feel it will be discovered,” he observes. “But,” he adds, “it may be more exciting eventually if it is not discovered.”