With a handover ceremony at the end of June, an exciting year of hard work on DESY’s new synchrotron radiation source, PETRA III, came to a successful conclusion for the construction team of general contractor Ed. ZÜBLIN and the DESY project team. They had completed the experimental hall within a year, exactly on schedule. As early as 7 April, DESY was able to take responsibility for the concrete slab on which the new part of the storage ring tunnel and the experiments are being set up. This latest project is the third reincarnation for the PETRA storage ring, which began life as a leading electron–positron collider in the 1980s and later became a pre-accelerator for HERA, the proton–electron collider. It will provide researchers at DESY with one of the most brilliant X-ray sources in the world.

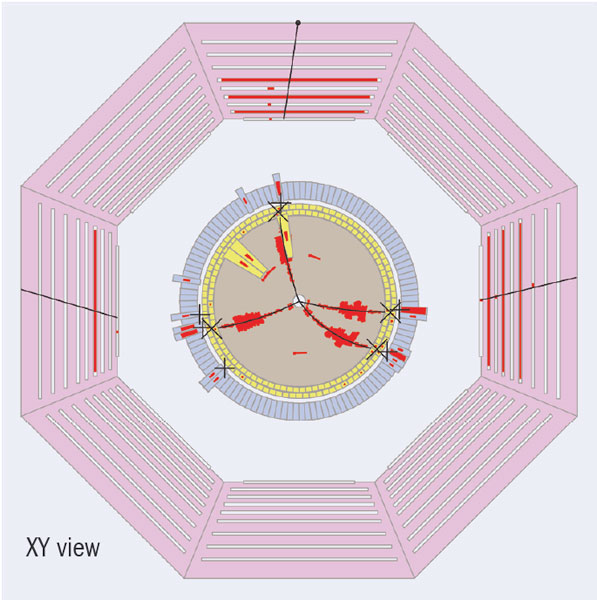

Image credit: DESY.

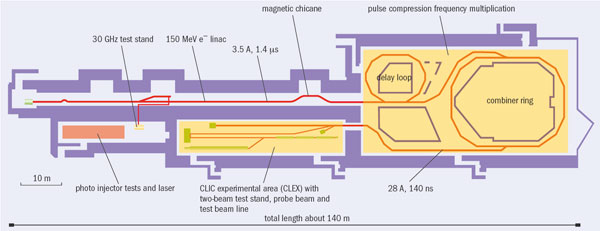

The PETRA III project comprises the reconstruction of the PETRA accelerator to form a dedicated third-generation synchrotron radiation source together with 14 independent beamlines serving up to 30 experimental stations. An eighth of the ring (288 m long) has been completely remodelled within a new hall that also houses the experiments, and the remainder of the ring (some 2 km) has been completely refurbished. The overall budget of the project was €225 million, shared between the German Federal Government (90%) and the City of Hamburg (10%).

High brilliance guaranteed

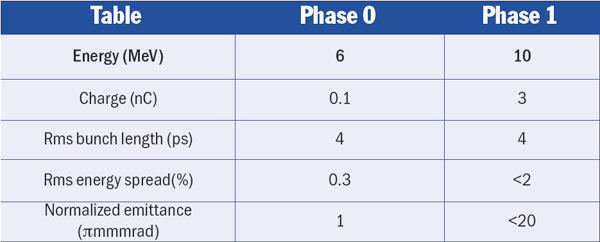

PETRA III will have the lowest emittance – 1 nm rad – of all the high-energy (6 GeV) storage rings in the world. This will be achieved by installing 80 m of damping wigglers in two of the long straight parts of the ring. The high brilliance will be assured by undulators, where periodic magnetic fields force the beam to oscillate and emit intense radiation in a narrow energy band. To free space for the undulators in the new arc, the classic FODO lattice (the basic combination of quadrupole and dipole magnets) has been replaced by a Chasman-Green lattice, which is better optimized for light sources. There the magnets are mounted on girders carrying either two quadrupoles and one dipole, or three quadrupoles.

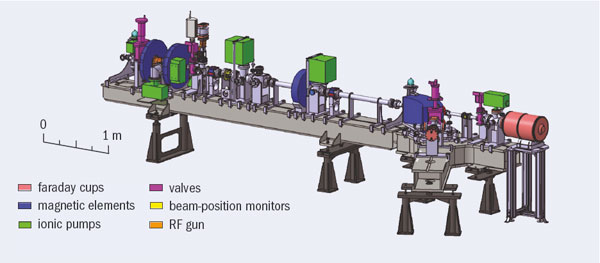

The project officially started in 2004 with the publication of the Technical Design Report (TDR). In the following years an increasing number of DESY staff worked on the detailed planning and preconstruction of accelerator and beamline components, and preparations for the construction activities on the DESY campus finally started in May 2007. However, disassembly of the old accelerator and preparation of the construction site could not start until 2 July 2007, after the last electrons and protons had been delivered to HERA. All the accelerator components had to be removed from the tunnel, an operation that was achieved in only three months. The magnets were refurbished, most of them receiving new coils, and magnetically characterized. They were then mounted again together with the new vacuum system, and in May 2008 the last dipole was installed in its old position. As the plan is for PETRA III to operate in top-up mode, where the storage ring current is kept almost constant with frequent injections of beam, the pre-accelerators and part of the general infrastructure also had to be refurbished.

The old PETRA tunnel had to be completely removed in the arc where the new experimental hall was being built. In designing the new hall, extreme care was taken to ensure optimum stability, both for the storage ring and the future X-ray beamlines. The hall floor is cast as a monolithic 1 m thick concrete slab that will support all the components. This slab is mechanically isolated from its surroundings by soft vibration-damping material, and the framework of the hall is built on sleeved piles to minimize the influence it could exert through the ground on the floor of the hall.

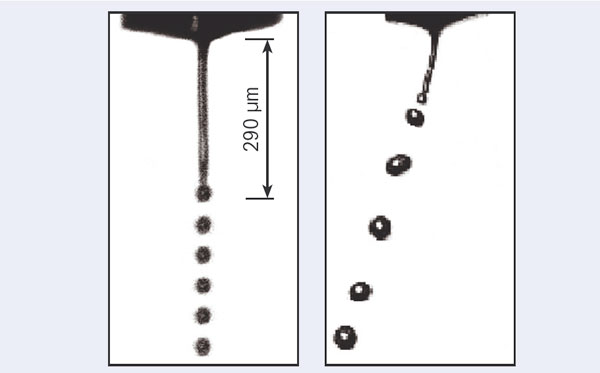

The optimum design of the sleeved piles had to be tested by producing four prototype piles – in effect, the first experiment at PETRA III. Using bubble-wrap foil to sleeve the piles proved to be the most economic and efficient solution. Then for two months, a long procession of trucks removed the sand covering the old tunnel in the section where the new experimental hall was to be built before the remaining 95 piles could be lowered 20 m deep into the ground. At the same time, the 1 m-thick layer of recycled concrete material was brought into place and carefully densified (i.e. hardened). The layer forms the subsoil for the concrete slab. This period of construction ended with the foundation-stone ceremony on 14 September 2007.

It took only two months to erect the hall. By November 2007 the roof was closed and the teams celebrated with a topping-out ceremony attended by German research minister, Annette Schavan. The most exciting task followed in mid-December: the casting of the 1 m-thick base slab. Within 60 hours, 38 trucks brought 860 loads of concrete (some 6700 m3) to the DESY campus where it was pumped into the hall. Half of the concrete (i.e. the upper half of the plate) is reinforced by steel fibres to minimize the number of cracks. The crucial part was the setting of what is possibly the longest single piece of concrete ever cast. During cool-down it performed exactly as predicted, shrinking by 8.2 cm and forming only one crack, which was cured by injecting epoxy resin. Preliminary measurements of the vibration and deformation properties gave promising results. In quiet periods the rms value of the vibrational amplitude at frequencies of above 1 Hz is as low as 20 nm. Finally, by 30 June 2008 work on the façade and the interior of the laboratories and evaluation rooms had finished on schedule.

Meanwhile, the first DESY groups have begun work inside the hall. All the points for the determination of the eventual beam position have been marked along the particle and X-ray beamlines. The laying of the cooling water pipes has started, and shielding stones for the tunnel have been set up inside the hall. Installation of the optics enclosures for the beamlines began in mid-July, and the erection of lead hutches to accommodate the experiments started at the beginning of August.

Experiments, which are organized in nine sectors, have been selected by an international advisory board based on the proposals collected in the TDR. All make use of the high brilliance of the PETRA III beam. Sector 1 will be dedicated to inelastic scattering of a few milli-electron-volts and nuclear resonant scattering with an energy resolution of nano-electron-volts, offering simultaneously a spatial resolution in the few or even submicron range. Sector 2 will be shared by a hard X-ray beamline, with one fixed energy end-station for powder diffraction and one for extreme conditions experiments, and one beamline for micro- and nano-small angle X-ray scattering applications. Sector 3 will house a variable polarization soft X-ray beamline equipped with an Apple-II type undulator and a selection of dedicated end-stations. Sector 4 is the imaging sector with one beamline for tomography (operated by the GKSS Research Centre, Geesthacht) and a hard X-ray nanoprobe beamline dedicated to spatially resolved absorption spectroscopy and fluorescence analysis.

In sector 5 GKSS and DESY will jointly operate a beamline for very hard X-rays (above 50 keV), dedicated mainly to applications in materials science. Sector 6 focuses on diffraction experiments with a very-high-resolution diffraction and a resonant scattering end-station. In addition, a station for electron spectroscopy will be included. Sector 7 makes special use of the high brilliance of PETRA III to perform experiments using the coherent flux. Both X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy and coherent imaging experiments are foreseen. The last two sectors, 8 and 9, are dedicated to applications in life science, with four beamlines operated together with the Max Planck society, the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research and, with the largest part of three experiments, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory. These beamlines will offer small angle scattering, macro-molecular crystallography and bio-imaging end-stations.

The schedule dictates that the technical commissioning of the machine will start in October, with the first beam expected at the beginning of 2009. During the commissioning of the beamlines, scheduled for spring and summer 2009, DESY will invite already “friendly” users to participate in the characterization of the experiments at this exciting new facility.