Chris Llewellyn Smith is no stranger to CERN. He served five years as director-general, from 1994 to 1998. During his mandate, LEP was successfully upgraded and the LHC project was approved. On his most recent visit to CERN, however, Llewellyn Smith did not address the audience gathered in the main auditorium on particle physics or high-energy accelerators. Instead, he talked about the shortage of energy sources in the world, a popular topic these days.

With the price of oil fluctuating, subjects such as “hydrogen-driven” cars, “solar-fed” devices and “biomasses” appear increasingly in newspapers and magazines, with various experts constantly presenting new scenarios. According to the International Energy Agency, a huge increase in energy use is expected in the coming decades. Most of it is needed to lift billions of people out of poverty, including more than 25% of the world’s population who still lack electricity.

Llewellyn Smith: from CERN to nuclear fusion.

Llewellyn Smith: from CERN to nuclear fusion.

Image credit: UKAEA.

According to Llewellyn Smith: “Fossil fuels supply 80% of the world’s primary energy. When they are exhausted, it currently looks as if much of their role will have to be taken over by nuclear fission (conventional nuclear reactors at first, then fast breeders when the cheaper uranium is exhausted), and possibly solar power, but this will need technological advances to decrease the cost, and in storage and transmission. And then, of course, we should use any alternative energy that works such as wind, biomasses and hydro. We also must become much more economical. For large-scale production power plants, we hope that a major role will be played by fusion.”

The idea of producing energy using nuclear fusion dates back to the early 1950s. About 20 years after its discovery, at the first Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy held in Geneva in 1955, Homi Bhabha said: “I venture to predict that a method will be found for liberating fusion energy in a controlled manner within the next two decades.” (Vandenplas and Wolf 2008). Unfortunately, after the first enthusiastic moments, major technological hurdles prevented fusion from becoming the easy option for energy supply that was originally expected.

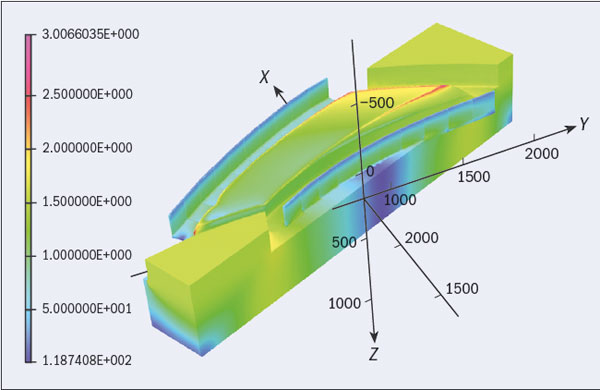

Now the future of fusion is ITER, the joint international research and development project that aims to demonstrate the scientific and technical feasibility of fusion power. “The biggest fusion device in the world at the moment is the Joint European Torus, JET, at Culham in the UK,” explains Llewellyn Smith. “In order to show that fusion can really work, we need to build something that is twice as big in every dimension and that will be ITER. There are other devices currently being built in the world but they are all smaller, so there is no competition for ITER.” Europe, Japan, Russia, US, China, South Korea and India are all involved in the ITER project. “Between them,” continues Llewellyn Smith, “these countries are home to more than half the population of the world. So, this is really a global response to a global problem.”

CERN is directly contributing to support ITER through some recently signed agreements (CERN Courier May 2008 p26). “ITER is starting from nothing,” says Llewellyn Smith, who is currently chairman of the ITER Council. “They need experts in a large number of areas and CERN can help by making expertise available. Some of these areas, such as superconductivity, have been used in fusion but not on the scale that has been used at CERN. The expertise of CERN people will certainly help to build up the project and make it work quickly.”

Strong links between CERN and the fusion facilities also exist at a more managerial level. Llewellyn Smith was called to lead the UK nuclear fusion programme after his mandate at CERN and then obtained the chair of the ITER Council, whereas CERN’s current director-general, Robert Aymar, did quite the opposite and came to CERN after having led the ITER project. “The first example of exchange between CERN and fusion dates back to John Adams in the 1960s,” confirms Llewellyn Smith. “He was an engineer who went from building the PS to founding the Culham fusion laboratory, which I now direct, and then went back to CERN to build the SPS.”

Particle physics and fusion use similar techniques, such as superconducting magnets, high-vacuum systems, RF systems, and detectors that have to work with high levels of radiation. However, it is not only the development of new technologies that Llewellyn Smith brought from CERN to the fusion projects; it is also the experience of big international scientific projects. “I joined fusion at a time when Europe was trying to reach agreement to build ITER with the other members,” he continues. “The experience that I had negotiating to get the Americans, Japanese, Russians, Indians, Canadians etc involved at CERN, was valuable; I had dealt with many of the governments in ITER before, and even many of the same people.”

Big projects have high potential but they also bring a great deal of uncertainty concerning their feasibility, the huge amount of money they cost and their actual duration. ITER is not even a real fusion reactor yet, it is an experimental device. It will take at least 10 years to build it and another decade to understand its results, and only then might people start building an actual prototype power station. “The time-scale is slow,” confirms Llewellyn Smith. “It is slow because we are dealing with very difficult, large-scale, first-of-a-kind projects. In fact, it will take considerably more than 30 years before fusion can be rolled out on a large scale. A very good question is if it will still be needed. The answer is ‘yes’, because the energy need is going to increase and – even forgetting about CO2 and climate change – at a certain point there will be no oil, no coal, and no gas, and we will really need additional options. So we have to go on with fusion as fast as we can.” As it seems inevitable that the world’s remaining fossil fuels will be used, “developing the technology to capture and store the CO2, and then deploying it on a large scale, must be a priority” according to Llewellyn Smith.

A particular attraction of fusion is that it is environmentally responsible. “Fusion doesn’t produce CO2, and it’s not possible to have some sort of runaway reaction or explosion,” explains Llewellyn Smith. “Fusion reactors can have all sorts of problems but it is very difficult to imagine accidents that will harm people. Fusion uses tritium, which is of course radioactive, but the active amount in a fusion power station will be less than a gram. The walls of the reactor become radioactive, but by choosing the materials correctly, we can make sure that the radioactivity has a half-life of around 10 years. So, a fusion reactor will become radioactive but 100 years later you could recycle the material. Unless you burn it, the waste from a conventional nuclear reactor is radioactive for many thousands of years.”

Changes in energy sources in the long-term future will alter the political balance of the world. Wealthy countries whose internal economy depends on the oil trade may become less wealthy, and western economies based on the use and transformation of oil derivatives may suffer from the change in the global energy scene. “The problem we face today is that the very poor countries generally have very limited energy resources,” says Llewellyn Smith. “One quarter of the world’s population has no electricity at the moment. They need more energy to enjoy anything like what we would regard as an acceptable standard of living. We need some sort of solidarity, and equity.” He adds: “At the moment 80% of our energy comes from oil, coal and gas, which are going to end in the next decades. So the world is going to be different. I can’t predict what it will be like but the concern is to make sure that it is viable for everybody. It is unlikely that very high-tech solutions like fusion will become widely available in less wealthy countries. So maybe we in the developing world should be adopting such high-tech solutions and they should be using fossil fuels as long as they last. That is a political problem.”

Politics and the role of science: this is an interesting point. How much are scientists driven by politicians and vice-versa? “In the end politicians must make the decisions,” says Llewellyn Smith. “The responsibility for scientists is to make sure that decisions are made on the basis of true facts. Long-term projects are very difficult to deal with because politicians only tend to look until the next election. They are beginning to say the right things about climate change, but words are not enough. We cannot stop the consequences of the things we are already doing, which will happen (e.g. rising temperatures) during the next 20 to 30 years. As scientists, it is our duty to make sure that governments understand what the potential solutions are and what alternative solutions should be developed. Our responsibility is providing information in an easy and understandable form.”

The primary concern of scientists is to understand the world, not change it, but as Llewellyn Smith concedes: “As a by-product they can help to change and shape it; in fusion we are trying to help shape the world by providing another major energy option.”