The US Department of Energy’s (DOE) Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility in Newport News, Virginia, has awarded four contracts as it begins a six-year construction project to upgrade the research capabilities of its 6 GeV, superconducting radio-frequency (SRF) Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF).

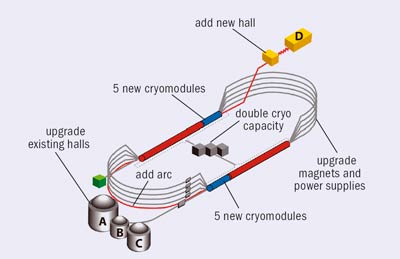

The resulting 12 GeV facility – with upgraded experimental halls A, B and C and a new Hall D – will provide new experimental opportunities for Jefferson Lab’s 1200-member international nuclear-physics user community.

The contracts are the first to be awarded following DOE’s recent approval of the start of construction. The DOE Office of Nuclear Physics within the Office of Science is the principal sponsor and funding source for the $310 million upgrade, with support from the user community and the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Under a $14.1 million contract, S B Ballard Construction, of nearby Virginia Beach, will build Hall D and the accelerator tunnel extension used to reach it as well as new roads and utilities to support it. Hall D civil construction is expected to last from spring 2009 until late summer 2011.

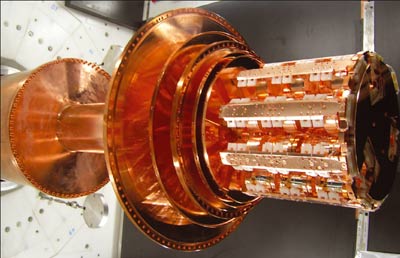

Two further contracts are for materials for Hall D’s particle detectors and related electronics. Under a $3.3 million contract, Kuraray of Japan will produce nearly 3200 km of plastic scintillation fibres for the new hall’s largest detector – a barrel calorimeter approximately 4 m long and nearly 2 m in outer diameter.

This calorimeter will detect and measure the positions and energies of photons produced in experiments. Its precision will allow the reconstruction of the details of particle properties, motion and decay. Under a $200,000 contract, Acam- Messelectronic GmbH of Germany will provide some 1440 ultraprecise, integrated time- to-digital converter chips for reading out signals from particles in experiments.

Last, a $1.5 million contract has gone to Ritchie-Curbow Construction of Newport News for a building addition needed for doubling the refrigeration capacity of CEBAF’s central helium liquefier, which enables superconducting accelerator operation at 2 K.

CEBAF already offers unique capabilities for investigating the quark–gluon structure of hadrons. Since operations began in the mid-1990s, more than 140 experiments have been completed.

The experiments have already led to a better understanding of a variety of aspects of the structure of nucleons and nuclei, as well as the nature of the strong force. These include the distributions of charge and magnetization in the proton and neutron; the distance scale where the underlying quark and gluon structure of strongly interacting matter emerges; the evolution of the spin-structure of the nucleon with distance; the transition between strong and perturbative QCD; and the size of the constituent quarks.

The beautiful programme of parity violation in electron scattering has permitted the precise determination of the strange quark’s contribution to the proton’s electric and magnetic form factors, with results that are in excellent agreement with the latest results from lattice QCD. This programme has placed new constraints on possible physics beyond the Standard Model.

New opportunities

Careful study in recent years by users and by the US Nuclear Science Advisory Committee has shown that a straightforward and comparatively inexpensive upgrade that builds on CEBAF’s existing assets would yield tantalizing new scientific opportunities.

The DOE study Facilities for the Future of Science: A Twenty-Year Outlook recommended the 12 GeV upgrade as a near-term priority. This 20-year plan used plain language to explain why. Speaking of quarks, it read: “As yet, scientists are unable to explain the properties of these entities – why, for example, we do not seem to be able to see individual quarks in isolation (they change their natures when separated from each other) or understand the full range of possibilities of how quarks can combine together to make up matter.”

The 12 GeV upgrade will enable important new thrusts in Jefferson Lab’s research programme, which generally involve the extension of measurements to higher values of momentum-transfer, probing correspondingly smaller distance scales. Moreover, many experiments that can run at a currently accessible momentum-transfer will run more efficiently at higher energy, consuming less beam time.

The generalized parton distributions will allow researchers to engage in nuclear tomography for the first time

For the first time nuclear physicists will probe the quark and gluon structure of strongly interacting systems to determine whether QCD gives a full and complete description of hadronic systems. The 12 GeV research programme will offer new scientific opportunities in five main areas. First, in searching for exotic mesons, in which gluons are an unavoidable part of the structure, researchers will explore the complex vacuum structure of QCD and the nature of confinement. Second, extremely high-precision studies of parity violation, developed to study the role of hidden flavours in the nucleon, will enable exploration of particular kinds of physics beyond the Standard Model on an energy scale that cannot be explored even with the proposed International Linear Collider.

The combination of luminosity, duty factor and kinematic reach of the upgraded CEBAF will surpass by far anything available through this kind of research. This will open up a third opportunity: by yielding a previously unattainable view of the spin and flavour dependence of the distributions of valence partons – the heart of the proton, where its quantum numbers are determined. The upgrade will also allow a similarly unprecedented look into the structure of nuclei, exploring how the valence-quark structure is modified in a dense nuclear medium. These studies will yield a far deeper understanding, with far-reaching implications for all of nuclear physics and nuclear astrophysics.

Lastly, the generalized parton distributions (GPDs) will allow researchers to engage in nuclear tomography for the first time – discovering the true 3D structure of the nucleon. The GPDs also offer a way to map the orbital angular momentum carried by the various flavours of quark in the proton.

New equipment

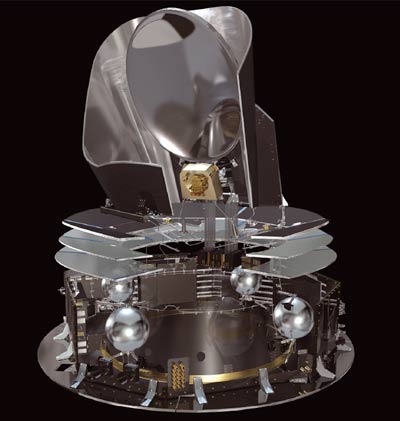

The CEBAF accelerator consists of two antiparallel 0.6 GV SRF linacs linked by recirculation arcs. With up to five acceleration passes, it serves three experimental halls with simultaneous, continuous-wave beams – originally with a final energy of up to 4 GeV, but now up to 6 GeV, thanks to incremental technology improvements. Independent beams are directed to the three existing experimental halls, each beam with fully independent current, a dynamic range of 105, high polarization and “parity quality” constraints on energy and position.

The maximum energy for five passes will rise to 11 GeV for the three original halls

The new Hall D will be built at the end of the accelerator, opposite the present halls. Experimenters in Hall D will use collimated beams of linearly polarized photons at 9 GeV produced by coherent bremsstrahlung from 12 GeV electrons passed through a crystal radiator. To send a beam of that energy to that location requires a sixth acceleration pass through one of the two linacs. This means adding arecirculation beamline to one of the arcs. It also requires augmenting the accelerator’s present 20 cryomodules per linac with five higher-performing ones per linac. Each 25-cryomodule linac will then represent 1.1 GV of accelerating capacity. The maximum energy for five passes will rise to 11 GeV for the three original halls, with experimental equipment upgraded in each.

As of early 2009, not only have the first contracts been awarded, but solicitations have been issued for about 40% of the total construction cost. CEBAF’s upgrade is the highest-priority recommendation of the Nuclear Science Advisory Committee’s December 2007 report The Frontiers of Nuclear Science: A Long Range Plan. “Doubling the energy of the JLab accelerator,” the report states, “will enable three-dimensional imaging of the nucleon, revealing hidden aspects of its internal dynamics. It will test definitively the existence of exotic hadrons, long-predicted by QCD as arising from quark confinement.” Efforts to realize this new scientific capability are now well underway.