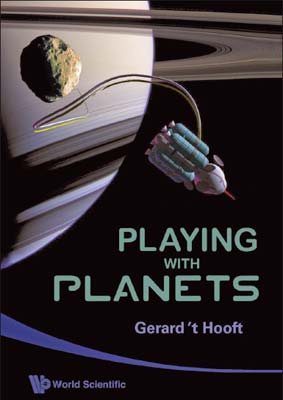

by Gerard ‘t Hooft, World Scientific. Hardback ISBN 9789812793072, £25 ($48). Paperback ISBN 9789812790200, £14 ($23).

At the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam they currently offer an audio tour by the artist Jeroen Krabbé. In a lovely, soft-accented English he recounts his personal experiences with the various exhibits over the many years that he has been visiting the museum – from the view as a child, a painter and actor, a parent and as a grand parent. His insights are both moving as well as fascinating and deep.

While reading Playing with Planets, I heard a similar voice in my head. Starting with personal experiences, Gerard ‘t Hooft lets his mind wander over the various aspects of life, speculating on the affects of new scientific developments on our lives in the future. The topics that he covers include flying kites (What is the highest you can possibly let a kite fly?), rising sea levels from global warming, modern dike construction and building floating cities on the ocean or in the sky. The topic that really grips his mind, however, seems to be space travel and colonization (mainly by robots), as well as ultimately moving around asteroids or even planets. (The latter is the origin of the title of the book.)

It is clearly important to ‘t Hooft that each of these speculations is firmly based on current scientific knowledge. They can thus be a motivation or even inspiration for actual scientific progress or technical developments. On this point he seems to take issue with the unfounded, wild speculations that he perceives to feature in most, if not all of, science-fiction writing. I am not much of a sci-fi buff myself, but to me such novels were always more of an enquiry into human nature – by placing people in unusual circumstances – rather than a real attempt at predicting or driving scientific progress. All the same, the author is well aware that he is stretching the limits of the possible when considering astro-mechanics.

My only criticism of his space-related speculations is that I believe they are severely constrained by the limited resources on Earth. When we realize that we have hit Peak Oil (or the equivalent for other materials), any interest in space travel and colonization will be put on the back burner. Nevertheless, I much enjoyed wandering the world, following this enquiring and original mind.