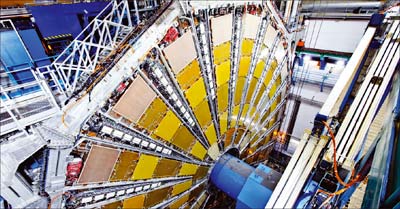

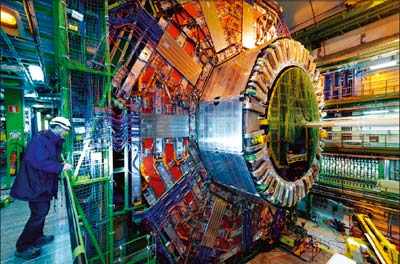

The LHC at CERN is about to start the direct exploration of physics at the tera-electron-volt energy scale. Early ground-breaking discoveries may be possible, with profound implications for our understanding of the fundamental forces and constituents of the universe, and for the future of the field of particle physics as a whole. These first results at the LHC will set the agenda for further possible colliders, which will be needed to study physics at the tera-electron-volt scale in closer detail.

Once the first inverse femtobarns of experimental data from the LHC have been analysed, the worldwide particle-physics community will need to converge on a strategy for shaping the field over the years to come. Given that the size and complexity of possible accelerator experiments will require a long construction time, the decision of when and how to go ahead with a future major facility needs to be undertaken in a timely fashion. Several projects for future colliders are currently being developed and soon it may be necessary to set priorities between these options, informed by whatever the LHC reveals at the tera-electron-volt scale

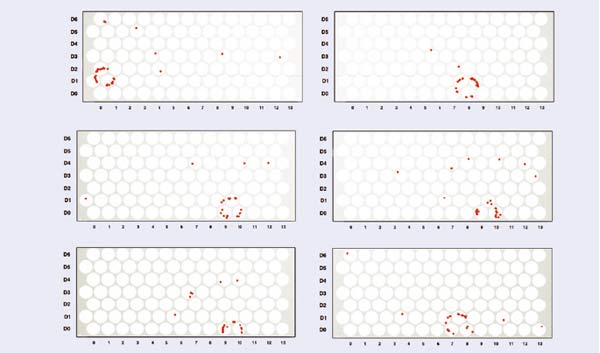

The CERN Theory Institute “From the LHC to a Future Collider” reviewed the physics goals, capabilities and possible results coming from the LHC and studied how these relate to possible future collider programmes. Participants discussed recent physics developments and the near-term capabilities of the Tevatron, the LHC and other experiments, as well as the most effective ways to prepare for providing scientific input to plans for the future direction of the field. To achieve these goals, the programme of the institute centred on a number of questions. What have we learnt from data collected up to this point? What may we expect to know about the emerging new physics during the initial phase of LHC operation? What do we need to know from the LHC to plan future accelerators? What scientific strategies will be needed to advance from the planned LHC running to a future collider facility? To answer the last two questions, the participants looked at what to expect from the LHC with a specific early luminosity, namely 10 fb–1, for different scenarios for physics at the tera-electron-volt scale and investigated which strategy for future colliders would be appropriate in each of these scenarios. Figure 1 looks further ahead and indicates a possible luminosity profile for the LHC and its sensitivity to new physics scenarios to come.

Present and future

The institute’s efforts were organized into four broad working groups on signatures that might appear in the early LHC data. Their key considerations were the scientific benefits of various upgrades of the LHC compared with the feasibility and timing of other possible future colliders. Hence, the programme also included a series of presentations on present and future projects, one on each possible accelerator followed by a talk on the strong physics points. These included the Tevatron at Fermilab, the (s)LHC, the International Linear Collider (ILC), the LHeC, the Compact Linear Collider (CLIC) concept and a muon collider.

Working Group 1, which was charged with studying scenarios for the production of a Higgs boson, assessed the implications of the detection of a state with properties that are compatible with a Higgs boson, whether Standard Model (SM)-like or not. If nature has chosen an SM-like Higgs, then ATLAS and CMS are well placed to discover it with 10 fb–1 (assuming √s = 14 TeV, otherwise more luminosity may be needed) and measure its mass. However, measuring other characteristics (such as decay width, spin, CP properties, branching ratios, couplings) with an accuracy better than 20–30% would require another facility.

The ILC would provide e+e– collisions with an energy of √s = 500 GeV (with an upgrade path to √s = 1 TeV). It would allow precise measurements of all of the quantum numbers and many couplings of the Higgs boson, in addition to precise determinations of its mass and width – thereby giving an almost complete profile of the particle. CLIC would allow e+e– collisions at higher energies, with √s = 1–3 TeV, and if the Higgs boson is relatively light it could give access to more of the rare decay modes. CLIC could also measure the Higgs self-couplings over a large range of the Higgs mass and study directly any resonance up to 2.5 TeV in mass in WW scattering.

Working Group 2 considered scenarios in which the first 10 fb–1 of LHC data fail to reveal a state with properties that are compatible with a Higgs boson. It reviewed complementary physics scenarios such as gauge boson self-couplings, longitudinal vector-boson scattering, exotic Higgs scenarios and scenarios with invisible Higgs decays. Two generic scenarios need to be considered in this context: those in which a Higgs exists but is difficult to see and those in which no Higgs exists at all. With higher LHC luminosity – for instance with the sLHC, an upgrade that gives 10 times more luminosity – it should be possible in many scenarios to determine whether or not a Higgs boson exists by improving the sensitivity to the production and decays of Higgs-like particles or vector resonances, for example, or by measuring WW scattering. The ILC would enable precision measurements of even the most difficult-to-see Higgs bosons, as would CLIC. The latter would be also good for producing heavy resonances.

Working Group 3 reviewed missing-energy signatures at the LHC, using supersymmetry as a representative model. The signals studied included events with leptons and jets, with the view of measuring the masses, spins and quantum numbers of any new particles produced. Studies of the LHC capabilities at √s = 14 TeV show that with 1 fb–1 of LHC luminosity, signals of missing energy with one or more additional leptons would give sensitivity to a large range of supersymmetric mass scales. In all of the missing-energy scenarios studied, early LHC data would provide important input for the technical and theoretical requirements for future linear-collider physics. These include the detector capabilities where, for example, the resolution of mass degeneracies could require exceptionally good energy resolution for jets, running scenarios, required threshold scans and upgrade options – for a γγ collider, for instance, and/or an e+e– collider operating in “GigaZ” mode at the Z mass. The link with dark matter was also explored in this group.

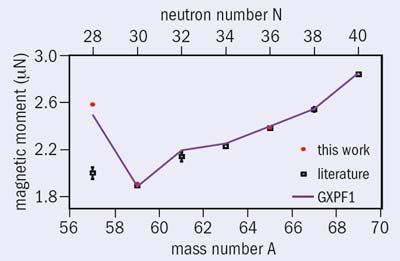

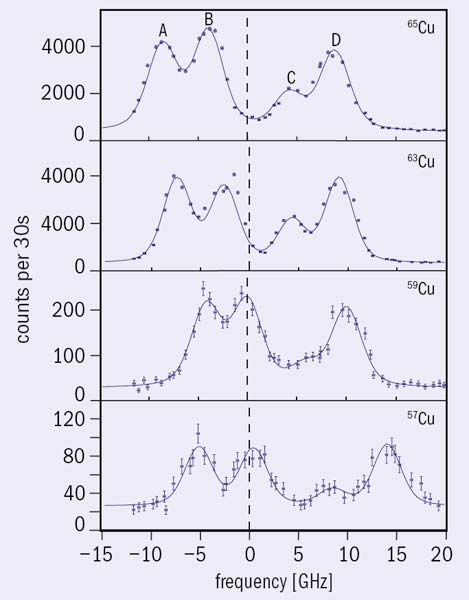

Image credit: Sven Heinemeyer.

Working Group 4 studied examples of phenomena that do not involve a missing-energy signature, such as the production of a new Z’ boson, other leptonic resonances, the impact of new physics on observables in the flavour sector, gravity signatures at the tera-electron-volt scale and other exotic signatures of new physics. The sLHC luminosity upgrade has the capability to provide additional crucial information on new physics discovered during early LHC running, as well as to increase the search sensitivity. On the other hand, a future linear collider – with its clean environment, known initial state and polarized beams – is unparalleled in terms of its abilities to conduct ultraprecise measurements of new and SM phenomena, provided that the new-physics scale is within reach of the machine. For example, in the case of a Z’, high-precision measurements at a future linear collider would provide a mass reach that is more than 10 times higher than the centre-of-mass energy of the linear collider itself. Attention was also given to the possibility of injecting a high-energy electron beam onto the LHC proton beam to provide an electron–proton collider, the LHeC. Certain phenomena such as the properties of leptoquarks could be studied particularly well with such a collider; for other scenarios, such as new heavy gauge-boson scattering, the LHeC can contribute crucial information on the couplings, which are not accessible with the LHC alone.

The physics capabilities of the sLHC, the ILC and CLIC are relatively well understood but will need refinement in the light of initial LHC running. In cases where the exploration of new physics might be challenging at the early LHC, synergy with a linear collider could be beneficial. In particular, a staged approach to linear-collider energies could prove promising.

The purpose of this CERN Theory Institute was to provide the particle-physics community with some tools for setting priorities among the future options at the appropriate time. Novel results from the early LHC data will open exciting prospects for particle physics, to be continued by a new major facility. In order to seize this opportunity, the particle-physics community will need to unite behind convincing and scientifically solid motivations for such a facility. The institute provided a framework for discussions now, before the actual LHC results start to come in, on how this could be achieved. In this context, the workshop report was also mentioned and made available to the European Strategy Session of the CERN Council meetings in September 2009. We now look forward to the first multi-tera-electron-volt collisions in the LHC, as well as to the harvest of new physics that these results will provide.

• For more about the institute, see http://indico.cern.ch/conferenceDisplay.py?confId=40437. The institute summary is available at http://arxiv.org/abs/0909.3240.