On 30 March, just one month after CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) had restarted for 2010, control rooms around the 27 km ring echoed with cheers as the machine produced the first collisions at a record energy of 7 TeV in the centre of mass. Over the following days, the LHC experiments started to amass millions of events during long periods of running with stable beams, thus beginning an extended journey of exploration at a new energy frontier.

Golden orbit

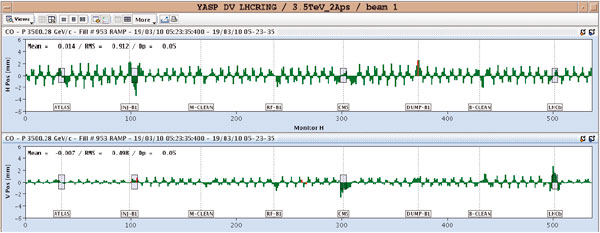

The first taste of beam for 2010, on 28 February, was at 450 GeV, the injection energy from the SPS (CERN Courier April 2010 p6). Operating the LHC at this energy soon became routine, allowing the teams to perform the tests necessary to optimize the beam orbit and the collimation, as well as the injection and extraction procedures. This work resulted in the definition of the parameters for collimation and machine protection devices for a “golden” reference orbit, with excellent reproducibility. It showed that the collimation system works as designed, with beam “cleaning” and other losses exactly where expected at the primary collimators. The tests also involved systematic and thorough testing of the beam dumping system, which proved to work well. One mystery about the beam still remains: the “hump”, a broad frequency-driven beam excitation that leads to an increase in the vertical beam size. Nevertheless, the teams measured good beam lifetimes, and in just under two weeks, on 12 March, the operators were able to ramp the beams up to 1.18 TeV, the highest energy achieved in 2009 (CERN Courier January/February p24).

A short technical stop followed, during which the magnet and magnet protection experts continued their campaign to commission the machine to 6 kA – the current needed in the main magnets to operate at 3.5 TeV per beam. A key feature is the quench protection system (QPS): on detecting the first indication that part of a superconducting magnet coil is turning normally conducting – quenching – it forces the whole coil to become normally conducting, thereby distributing the energy of the magnet current over its whole length. In the induced quench, the huge amount of energy stored in the coil is safely extracted and “dumped” into specially designed resistors. At the same time the QPS triggers a mechanism to dump beam within three turns.

In 2009, the system was fully commissioned to 2 kA, the current necessary to reach an energy of 1.18 TeV. However, during the final stages of hardware commissioning in February, multiple induced quenches sometimes occurred during powering off. It turns out that the system can be “over-protective”, because transient signals unrelated to real quenches can trigger controlled quenches. Once the problem was understood, the machine protection experts decided that they could solve it by changing thresholds in the magnet circuits equipped with the new QPS. For those parts with the old QPS, however, the solution required a modification to cards in the tunnel (to delay one of the transients). While awaiting full tests before implementing these changes (later in April), the experts took the decision to go ahead and run the main bending magnets up to 6 kA, but to limit the ramp rate to 2 A/s to reduce the transients.

By midday on 18 March the operators had the green light to try ramping to 6 kA at the agreed slow rate, first testing this ramp rate to 2 kA (1.18 TeV). By 10.00 p.m., after one or two interruptions, they had succeeded with a “dry ramp”, without beams. Work on beam injection and orbit corrections followed before a ramp started at around 4.00 a.m. with a low-intensity probe beam – about 5 × 109 protons in a single bunch per beam. Gradually, the current in the main bending magnets rose from 460 to 5850 A and at about 5.23 a.m. the beams reached 3.5 TeV – a new world record at the first attempt. Already, measurements suggested a lifetime for both beams of as long as 100 hours.

Over the following days, machine studies at 3.5 TeV continued, with ramping becoming routine and the orbit stable and reproducible. Just as at 450 GeV, machine protection and collimation studies were important before the step to collisions at 3.5 TeV could take place. Only then would the operators be able to declare “stable beam” conditions so that the experiments could turn on the most sensitive parts of their detectors to observe events at the new high-energy frontier.

With some critical work still remaining, on 23 March the management took the decision to announce that the first attempt at collisions would take place a week later, on 30 March, with invited media in full attendance. The following days were not without difficulties, as a variety of hardware problems occurred, and each morning saw a change of plans in the run-up to the first collisions at 3.5 TeV per beam. Further planned running at 450 GeV and studies at higher intensities at 450 GeV were among the casualties. By 29 March, however, the operators had performed all of the essential tests for declaring “stable beams” at 3.5 TeV and were able to run the machine for several hours at a time, with a non-colliding bunch pattern to avoid premature collisions in any of the experiments.

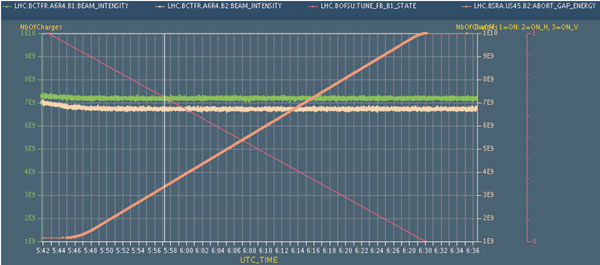

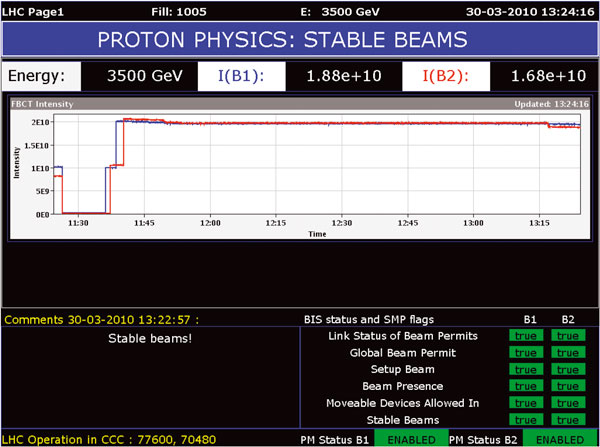

Finally at 4.00 a.m. on 30 March the LHC team was ready to inject beam in a colliding bunch pattern with two bunches per beam, in preparation for collisions. After the necessary checks, they began the ramp to 3.5 TeV at 6.00 a.m. just as the first media were arriving on CERN’s Meyrin site. Twice, part of the machine tripped during the ramp and twice the operators had to ramp back down and re-establish beam at 450 GeV. The third attempt, however, from 11.52 a.m. to 12.38 p.m., was successful. Then, after some final measurements on the beam, it was time to remove the “separation bumps” – the fields in corrector magnets that are used to keep the beams separated at the interaction points during the ramp.

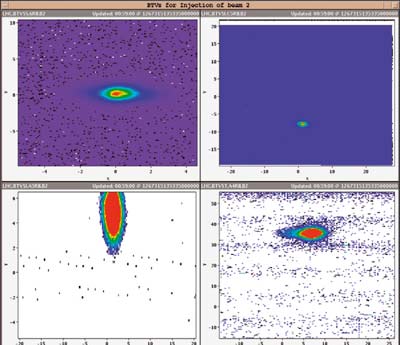

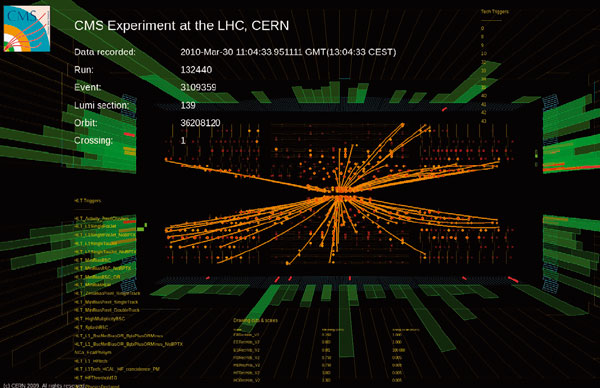

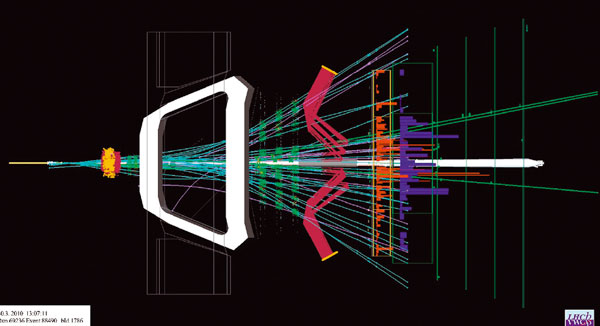

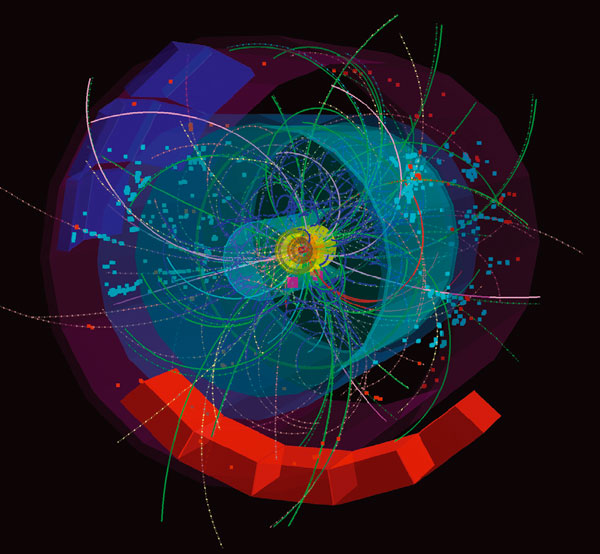

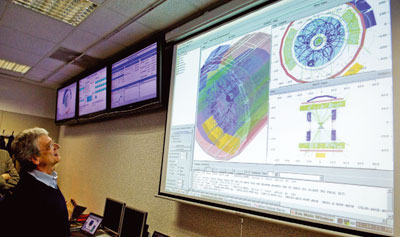

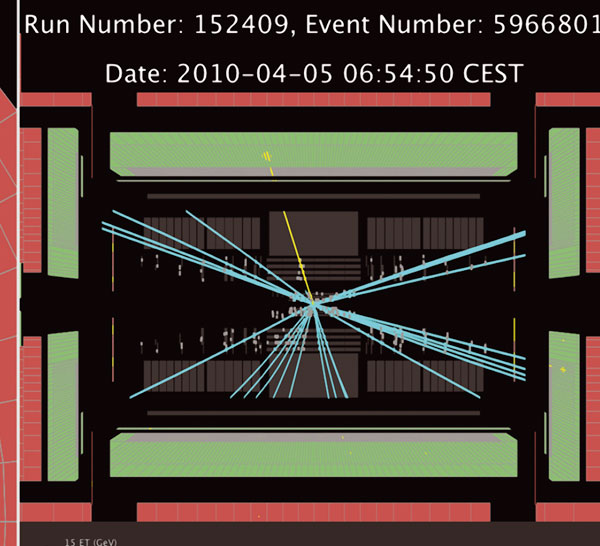

At 12.52 p.m. the operators announced that they were happy with the beam orbit and were about to remove the separation bumps. At 12.57 p.m. online beam and radiation monitors indicated that the CMS experiment had collisions, confirmed almost immediately by the online event displays. At 12.58 p.m. the ATLAS collaboration saw the experiment’s first events at a total energy of 7 TeV burst onto the screens of the crowded control room. At 12.59 p.m. the LHCb experiment saw its first collisions and by 1.01 p.m. the ALICE website was announcing its first 7 TeV events. At the same time, the two smaller LHC experiments also reported collisions. The TOTEM experiment saw tracks in one of its particle telescopes, while the LHCf calorimeters recorded particle showers with more than 1 TeV of energy. CERN’s press office swiftly told the assembled media and reported the successful observation of collisions at 7 TeV total energy to the world: the LHC research programme had finally begun.

At 1.22 p.m. the operators declared “stable beams” and the LHC provided three and a half hours of collisions before an error caused the beams to dump safely. During this time, CMS, for example, collected around 600,000 collision events and LHCf detected as many as 30,000 high-energy showers.

The following week saw several prolonged periods of “quiet” running during which the experiments continued to accumulate events. These were interspersed with further tests and machine development work. There were also scheduled periods for access to the tunnel, for example to begin work on the QPS to allow a faster ramp rate of 10 A/s. There was also the almost inevitable “down time” that arises with any complex machine.

The challenge ahead for the LHC team is to increase the luminosity, which is a measure of the collision rate in the experiments. The design luminosity is 1034 cm–2 s–1, but in these early days the experiments are seeing around 1027 cm–2 s–1. It is a case of learning to walk in small steps before running flat out, especially considering the total energy of the beams at higher luminosities. This is why the first investigations are always performed with the low-intensity “probe” beam.

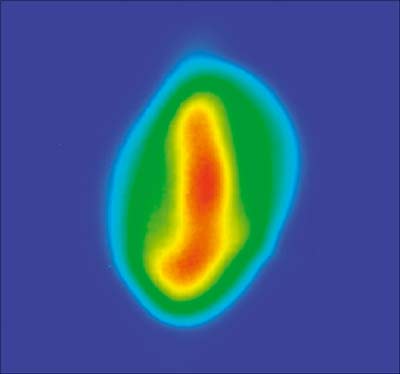

The luminosity depends not only on how many particles are in the beams, but also on making sure that the beams collide head-on exactly at the interaction points. Ensuring that this happens is the goal of dedicated “luminosity scans” in horizontal and vertical beam position for the experiments at each of the four interaction points. In addition, the LHC operators can reduce the beam size at the collision points by “squeezing” the betatron function that describes the amplitude of the betatron oscillations about the nominal orbit. On 1 April the first squeeze from 11 m down to 2 m was successfully performed in several steps at Points 1 and 5, where ATLAS and CMS are located (together with LHCf and TOTEM, respectively).

By the end of the first week of April, each of the four large experiments had accumulated some 300 μb–1 of data, corresponding to several million inelastic events. When optimized and with about 1.1 × 1010 protons per bunch, they were recording data at a rate of up to around 120 Hz and finding a luminosity lifetime of well in excess of 20 hours. The first stage of the journey to attain 1 fb–1 before a long shutdown towards the end of 2011 had begun.