Résumé

L’hadronthérapie par ions carbone en pleine expansion au Japon

Avec un premier patient traité en 1994, le Japon s’est imposé comme précurseur dans l’utilisation des ions carbone pour le traitement des tumeurs. Le 16 mars dernier, un patient souffrant d’un cancer de la prostate a été traité pour la première fois à l’aide d’un faisceau d’ions carbone dans un nouvel établissement du GHMC, le centre de soin et de recherche dédié au traitement par ions lourds de l’université de Gunma, trois ans après le début de sa construction, en février 2007. Il s’agit d’un modèle réduit de l’HIMAC, le premier accélérateur d’ions lourds utilisé à des fins thérapeutiques situé à Chiba. D’ici 2014, le Japon comptera cinq centres de traitement par ions carbone et huit par protons.

Image credit: Koji Noda.

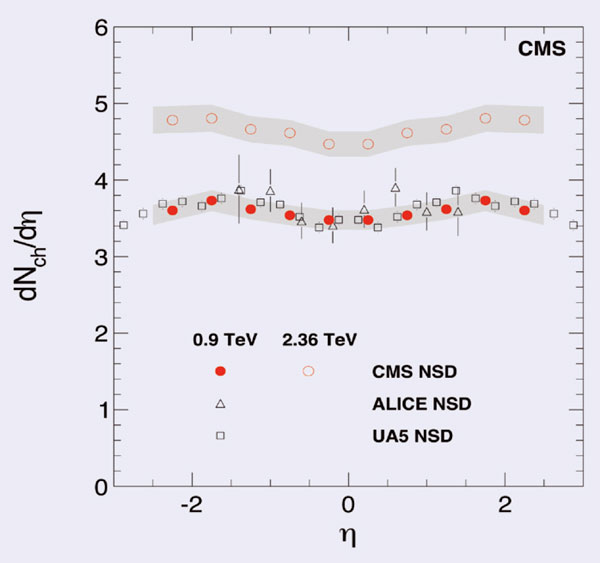

The first prostate cancer patient was successfully treated with a 380 MeV/u carbon-ion beam at a new facility of the Gunma University Heavy Ion Medical Center (GHMC) on 16 March, three years after construction began in February 2007. This facility, which is a pilot project to boost carbon-ion radiotherapy in Japan, has been developed in collaboration with the National Institute of Radiological Sciences (NIRS).

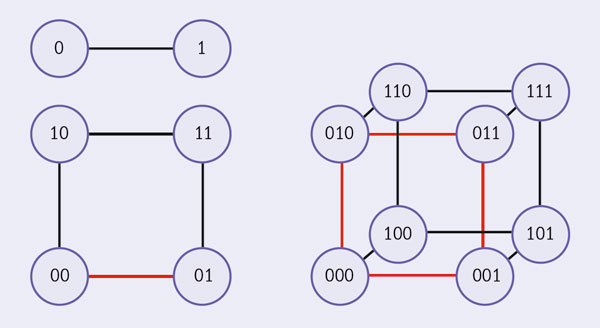

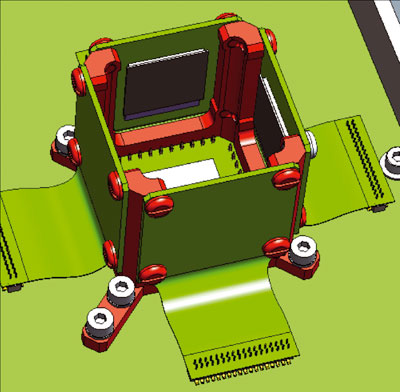

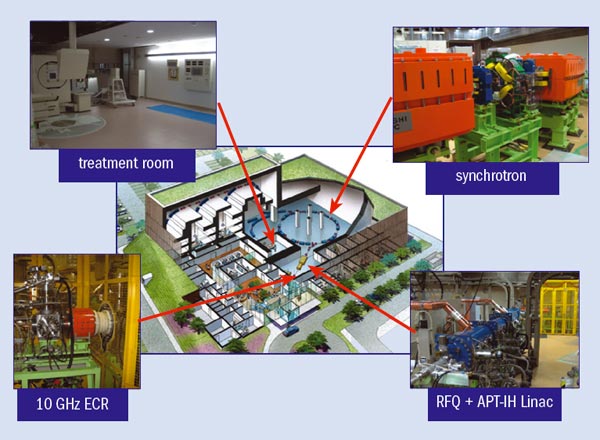

The GHMC facility, shown schematically in figure 2, can deliver carbon-ion beams with energies ranging from 140 to 400 MeV/u. It consists of a compact injector, a synchrotron ring, three treatment rooms and an irradiation room for the development of new beam-delivery technology. The first beam was obtained from the accelerator system on 30 August 2009. Beam commissioning was followed by three months of pre-clinical research before the first treatment began. Each week since has seen two patients added to the schedule. The facility is a pilot based on a smaller version of the Heavy-Ion Medical Accelerator in Chiba (HIMAC). This means that clinical instrumentation, as well as the accelerator system, has been better tailored for clinical use and has a much lower cost – about a third less than the HIMAC facility.

Clinical trials

Image credit: Koji Noda.

Heavy-ion beams are particularly suitable for deeply seated cancer treatment not only because of their high dose-localization at the Bragg peak but also as a result of the high biological effect around the peak (CERN Courier December 2006 p5). NIRS decided to construct the HIMAC facility in 1984, encouraged by the promising results from the pioneering work at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the 1970s. Completed in October 1993, HIMAC was the world’s first heavy-ion accelerator facility dedicated to medical use. A carbon-ion beam was chosen for HIMAC, based on the fast-neutron radiotherapy experience at NIRS. It uses the single beam-wobbling method – a passive beam-delivery method – because it is robust with respect to beam errors and offers easy dose management.

Since the first clinical trial in June 1994, the total number of treatments with HIMAC had reached more than 5500 by February 2010, including about 750 treatments in 2009 alone, with single-shift operation on an average of 180 days a year. The treatment has been applied to various types of malignant tumour. As a result of the accumulated numbers of protocols, in 2003 the Japanese government approved carbon-ion radiotherapy with HIMAC as a highly advanced medical technology.

The development of beam-delivery and accelerator technologies has significantly contributed to improved treatments at HIMAC. For example, NIRS developed methods for treating tumours that move with a patient’s breathing and for reducing the undesired extra dose on healthy tissue around tumours that occurs in the single beam-wobbling method, routinely used at HIMAC.

The carbon-ion radiotherapy with HIMAC has so far proved to be significantly effective not only against many kinds of tumour that have been treated by low-linear energy transfer (LET) radiotherapy but also against radio-resistant tumours, while keeping the quality of life high without any serious side effects. It has also reduced the number of treatment fractions, which leads to a short course of treatment compared with low-LET radiotherapy. For example, a single fractionated irradiation with four directions has been used in treating lung cancer, which means only one day of treatment. NIRS therefore proposed a new facility to boost the application of carbon-ion radiotherapy, with the emphasis on a downsized system to reduce costs.

Image credit: Koji Noda.

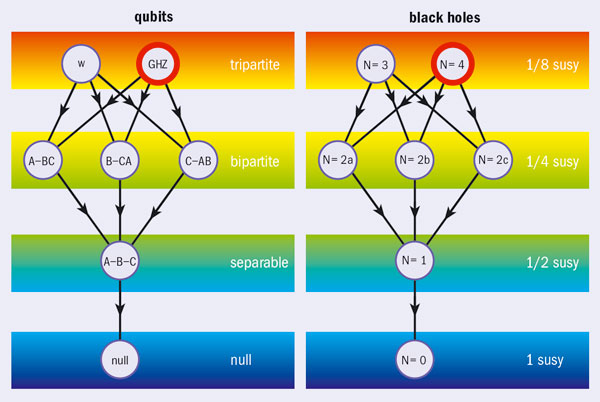

The design of the proposed facility was based on more than 10 years of experience with treatments at HIMAC. The key technologies for the accelerator and beam-delivery systems that needed to be downsized for the new facility were developed from April 2004 to March 2006, and their performances were verified by beam tests with HIMAC. In particular, the prototype injector system consisted of a compact 10 GHz electron-cyclotron resonance ion-source consisting of permanent magnets together with radio-frequency quadrupole (RFQ) and alternating-phase-focused interdigital H-mode (APF-IH) linear accelerators. This was constructed and tested at HIMAC because an APF-IH linear accelerator had never been constructed for practical use anywhere else. Tests verified that the injector system could deliver 4 MeV/u C4+ with an intensity of more than 400 eµA and transmission efficiency of around 80% from the RFQ to the APF-IH. This R&D work bore fruit in the recently opened GHMC facility.

NIRS, on the other hand, has been engaged in research on new treatments since April 2006 with a view to further development of the treatments at HIMAC. One of the most important aims of this project is to realize an “adaptive cancer radiotherapy” that can treat tumours accurately according to their changing size and shape during a treatment period. A beam-scanning method with a pencil beam, which is an active beam-delivery method, is recognized as being suitable for adaptive cancer radiotherapy.

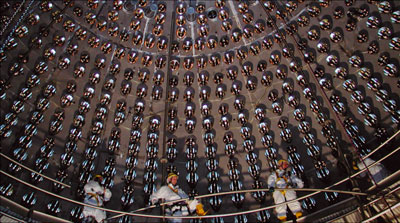

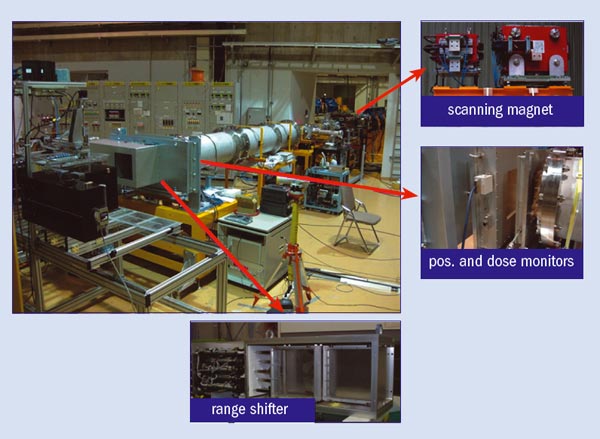

Image credit: Koji Noda.

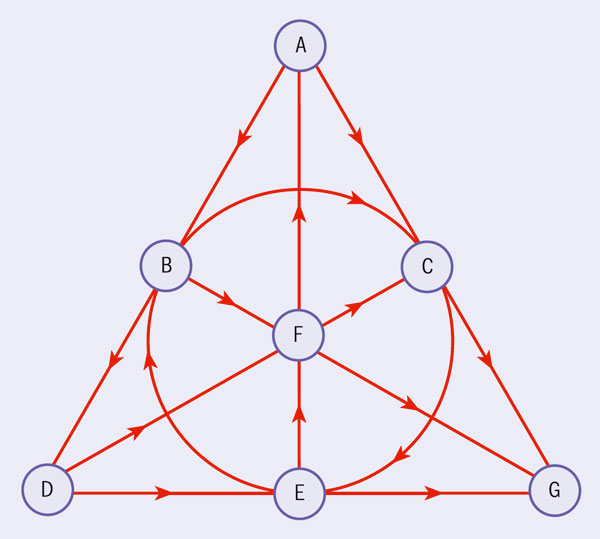

NIRS, which treats both fixed and moving tumours, has proposed a fast 3D rescanning method with gated irradiation as a move towards the goal of adaptive cancer radiotherapy for treating both kinds of tumour. There are three essential technologies used in this method: new treatment planning that takes account of the extra dose when an irradiation spot moves; an extended flattop-operation of the HIMAC synchrotron, which reduces dead-time in synchrotron operation; and high-speed scanning magnets. These allow for 3D scanning that is about 100 times faster than conventional systems. Experiments using a test bench at the HIMAC facility (figure 3) have verified that the desired physical dose distribution is successfully obtained for both fixed and moving targets, with the expected result for the survival of human salivary-gland cells.

Image credit: Koji Noda.

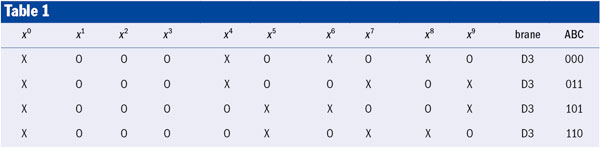

Using this technology, a new treatment research facility is being constructed at HIMAC (figure 4). The facility, which is connected to the HIMAC accelerator system, will have three treatment rooms: two rooms equipped with both horizontal and vertical beam-delivery systems and one room with a rotating gantry. The facility building was completed in March and one treatment room will be finished in September. Following beam commissioning and pre-clinical research, the first treatment should take place in March 2011.

Future outlook

Following on from the pilot facility at GHMC, two additional projects for carbon-ion radiotherapy have been initiated in Japan: the Saga Heavy Ion Medical Accelerator in Tosu (Saga-HIMAT) and the Kanagawa Prefectural project. The Saga-HIMAT project started construction of a carbon-ion radiotherapy facility in February 2010. This is based on the design of the GHMC facility and will be opened in 2013. Although this facility has three treatment rooms, two will be opened initially and use the spiral beam-wobbling method. Of these, one will be equipped with horizontal and vertical beam-delivery systems and the other with horizontal and 45° beam-delivery systems. In the next stage, the third room will be opened and use horizontal and vertical beam-delivery systems with the fast 3D rescanning method developed by NIRS. The Kanagawa Prefectural Government has decided to construct a carbon-ion radiotherapy facility in the Kanagawa Prefectural Cancer Center. This will also be based on the design of the GHMC-facility. Design work on the facility building began in April 2010 and it is expected to open in 2014.

More than 500,000 people in Japan are diagnosed with cancer every year and it is forecast that this number will continue to rise. In such a situation, the newly opened GHMC facility – following those at HIMAC and the Hyogo Ion Beam Medical Center – is expected to boost applications of carbon-ion radiotherapy in Japan. By 2014, five carbon-ion facilities and eight proton facilities will be operating. These are sure to play a key role in cancer radiotherapy treatment.