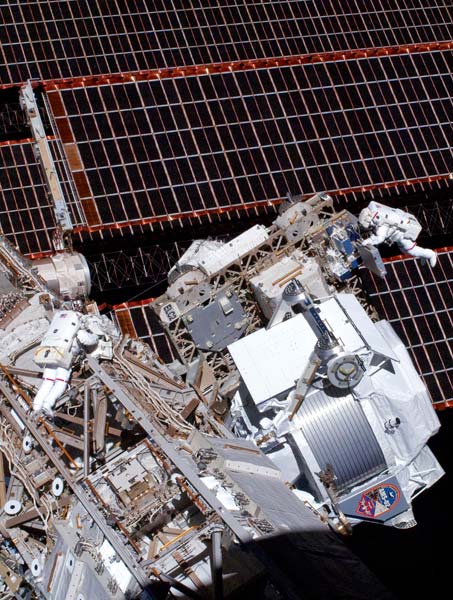

Image credit: NASA.

16 May 2011, 08:56 EDT : The Endeavour space shuttle takes off for its final trip into space. In its payload bay, it is carrying the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS-02), a large particle detector. For the 600 physicists and engineers who have been working on the AMS project for more than 15 years, it is a fantastic accomplishment, but the real excitement is only just beginning. Two days after take off, Endeavour will reach the International Space Station (ISS), where AMS-02 is installed. From this vantage point in space, the advanced detector will catch the tracks of cosmic rays for years to come.

Cosmic messengers

The Big Bang that gave rise to the universe about 13.7 billion years ago should have produced particles and antiparticles in equal amounts, as indeed happens in experiments at particle accelerators. So why is there no evidence of antimatter in the universe? This is one of the big questions of modern physics – one that the international AMS collaboration, led by Nobel laureate Sam Ting, is seeking to address. The mission will also join the search for dark matter in the universe and gather information on sources of cosmic rays.

Cosmic rays are energetic particles from outer space. Protons and the nuclei of helium together represent about 99% of the spectrum, while the remaining 1% is composed of heavier nuclei and electrons. The details of their origins remain unknown but they are probably produced in different cosmic objects, especially the most violent, such as supernova remnants. The sources must be powerful natural accelerators – more powerful than any achievable in laboratories on Earth.

AMS-02 is the first large magnetic spectrometer to fly into space for a long period of time, following on from its prototype, AMS-01, which flew aboard the space shuttle Discovery for 10 days in June 1998. It will allow the cosmic-ray spectrum to be measured with high precision. Such precise measurements are possible only from space, because the cosmic rays that bombard the Earth interact with the atmosphere. At the Earth’s surface it is possible to detect only the cosmic-ray showers that they produce, as the Pierre Auger Observatory in Argentina does, for example. The magnetic fields in space mean that it is impossible to deduce the location of any source of the primary charged particles by measuring their direction. However, determining the composition of the cosmic rays precisely is a key to knowing where they come from. All of the natural elements are present in cosmic rays in approximately the same ratio as in the Solar System, so detailed differences could reveal crucial information about the nature of their source – rather like fingerprints – and make it possible to identify the sources indirectly.

The requirements for operating in space are challenging and AMS-02 has been designed specially for this hostile environment. It has to resist vibrations and large temperature variations; it must operate in the vacuum of space and in the absence of gravity. In addition, the electronics have to be resistant to radiation. Other vital constraints also had to be considered in designing the detector, such as its weight and electrical consumption, both of which were strictly limited.

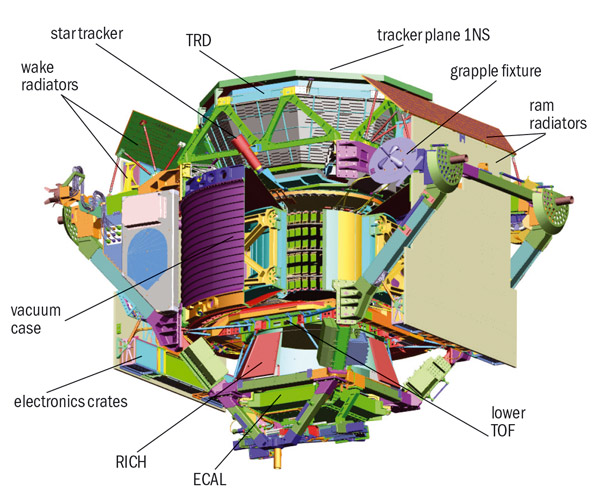

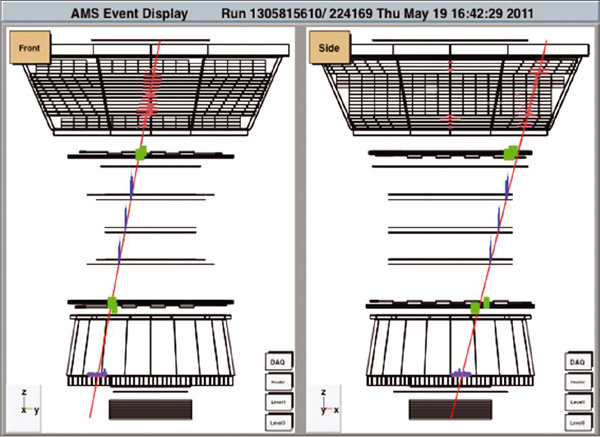

At the heart of AMS-02 is a powerful, permanent magnet that bends charged particles and antiparticles in opposite directions. This “magic ring” is designed specifically to ensure that the magnet has a negligible net dipole-moment, so avoiding a coupling with the Earth’s magnetic field that would otherwise disturb the orbit of the ISS. Around this magnet, several layers of detectors work together to identify particles passing through (figure 1, p19). The silicon tracker measures the trajectory deflection of charged particles, the ring-imaging Cherenkov (RICH) detector estimates their velocity and the electromagnetic calorimeter (ECAL) measures their energy. In addition, the transition radiation detector (TRD) identifies light particles by the detection of the X-rays that they emit. The time-of-flight (TOF) system acts as a trigger, alerting the subdetectors to an incident cosmic ray. An anti-coincidence counter was also developed to sort the events in real time, rejecting cosmic rays traversing the magnet walls and keeping the significant ones that really cross the overall detector. As a whole, AMS-02 is able to digitize 300,000 channels of data some 2000 times a second.

Image credit: AMS-02.

AMS-02 can recognize one antiparticle among a billion particles. This represents an increase in sensitivity of three orders of magnitude in comparison with previous experiments. With such precision, the detector will provide the composition of the cosmic-ray spectrum with unprecedented accuracy. This will enable the AMS collaboration to find either an explanation for the disappearance of antimatter or proof of its existence hidden away in a remote corner of the universe. The observation of just one antihelium nucleus would provide evidence for the existence of a large amount of antimatter somewhere in the universe – large enough for antiprotons to have undergone a process of nucleosynthesis. This matter could only have been generated soon after the Big Bang and would represent a real breakthrough in the current view of the universe.

Antiworlds and the dark universe

There are other puzzles about the universe that AMS can try to solve. Only 4% of the universe is accessible to telescopes and detectors through the radiation that it emits. The rest appears to be in the forms known as dark matter and dark energy, which account for about 23% and 73%, respectively, of the total matter and energy in the universe. In this case, AMS-02 is expected to play a key role by tracking possible signals from the annihilation of supersymmetric particles. One of the candidates for a dark-matter particle is the neutralino, a hypothetical particle that is predicted by supersymmetry. If neutralinos do indeed exist they could interact with each other, producing excesses of charged or neutral particles – creating anomalies in the overall cosmic-ray spectrum.

Particle physics, astroparticle physics and cosmology are certainly at a key moment in their history as AMS-02 enters the race

For this reason, AMS-02 has been eagerly awaited because it will probably be the only experiment able to confirm or invalidate results from other experiments that have recently been in the spotlight. In particular, two satellites, PAMELA and FERMI, as well as the ATIC balloon experiment flown above Antarctica, have all reported an excess of electrons and positrons in the cosmic-ray spectrum. Even though these different measurements are inconsistent with each other, they could all possibly fit with the scenario of dark-matter annihilation. Using a completely different approach, underground experiments such as Xenon, CDMS or Edelweiss, are currently providing strong competition in the detection of dark-matter particles. Moreover, in parallel the LHC is producing data that could in the next two years provide the first exciting news on dark matter.

Particle physics, astroparticle physics and cosmology are certainly at a key moment in their history as AMS-02 enters the race. “Better to light a candle than to curse the darkness,” goes a Chinese proverb. All eyes are now focused on the AMS-02 experiment, hoping that it will precisely light the candle on both the dark universe and the antiuniverse.

• AMS was built by an international collaboration involving large European participation from France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland,together with China, Taiwan, Russia and the US. It has been supported by the national high-energy institutes INFN, IN2P3, CIEMAT, the US Department of Energy, Academia Sinica (Taipei), Swiss National Fund, and by the space agencies ASI, DLR, NASA, and ESA. The detectors were integrated at CERN by the collaborating groups. Space qualification was at the ESTEC facilities in ESA.