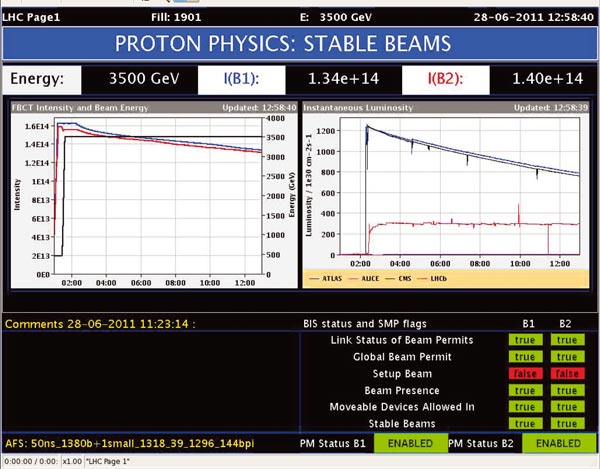

Since the early 1980s, the Quark Matter conferences have been the most important venue for showing new results in the field of high-energy heavy-ion collisions. The 22nd in the series, Quark Matter 2011, took place in Annecy on 22–29 May and attracted a record 800 participants. Scheduled originally for 2010, it had been postponed to take place six months after the start of the LHC heavy-ion programme. It was hence – after Nordkirchen in 1987 and Stony Brook in 2001 – the third Quark Matter conference to feature results from a new accelerator.

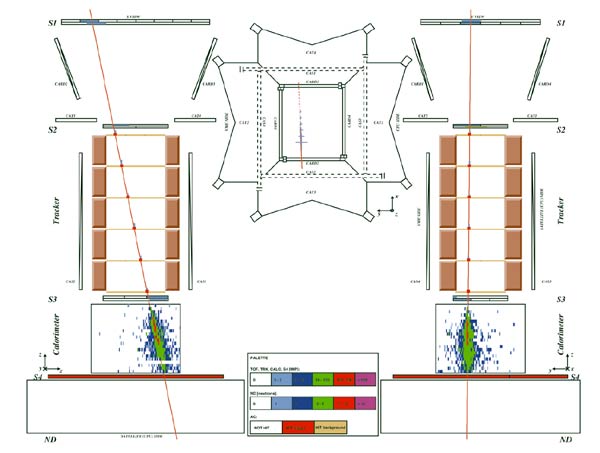

The natural focus of the conference was on the first results from the approximately 108 lead–lead (Pb+Pb) collisions that each of the three experiments – ALICE, ATLAS and CMS –participating in the LHC heavy-ion programme have recorded at the current maximum centre-of-mass energy of 2.76 TeV per equivalent nucleon–nucleon collision. In addition, the latest results from the PHENIX and STAR experiments at Brookhaven’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) and its recent beam energy-scan programme featured prominently, as well as data from the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) experiments. The conference aimed at a synthesis in the understanding of heavy-ion data over two orders of magnitude in centre-of-mass energy.

The meeting also covered a range of theoretical highlights in heavy-ion phenomenology and field theory at finite temperature and/or density. And although, as one speaker put it, the wealth of first LHC data contributed much to the spirit that “the future is now”, there were sessions on future projects, including the programme of the approved experiment NA61/SHINE at the SPS, plans for upgrades to RHIC, experiments at the Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research under construction in Darmstadt, a plan for a heavy-ion programme at the Nuclotron-based Ion Collider facility in Dubna, as well as detailed studies for an electron–ion programme at a future electron–proton/electron–ion collider, e-RHIC, at Brookhaven, or LHeC at CERN.

Following a long-standing tradition, the conference was preceded by a “student day” featuring a set of introductory lectures catering for the particular needs of graduate students and young postdocs, who represented a third of the conference participants. The official conference inauguration was held on the morning of 22 May in the theatre at Annecy, the Centre Bonlieu, with welcome speeches from CERN’s director-general, Rolf Heuer, the director of the Institut National de Physique Nucléaire et de Physique des Particules (IN2P3), Jacques Martino, and the president of the French National Assembly, Bernard Accoyer. The same morning session featured an LHC status report by Steve Myers of CERN and a theoretical overview by Krishna Rajagopal of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Quark Matter 2011 also continued the tradition of scheduling summary talks of all of the major experiments in the introductory session. When the 800 participants walked in for a late lunch on the first day from the Centre Bonlieu along the Lake of Annecy to the Imperial Palace business centre, the site of the parallel sessions in the afternoon, they had listened to experimental summaries by Jurgen Schukraft for ALICE, Bolek Wyslouch for CMS, Peter Steinberg for ATLAS, Hiroshi Masui for STAR and Stefan Bathe for PHENIX. These 25-minute previews set the scene for the detailed discussions of the entire week.

This short report cannot summarize all of the interesting experimental and theoretical developments but it illustrates the breadth of the discussion with a few of the many highlights. Examples from three particular areas must therefore suffice to illustrate the richness of the new results and their implications.

The importance of flow

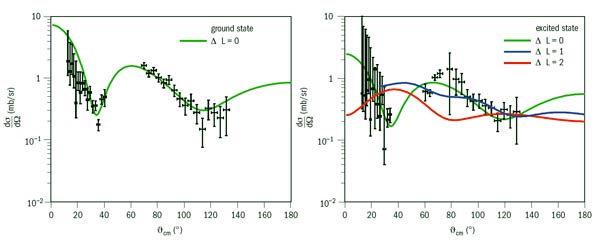

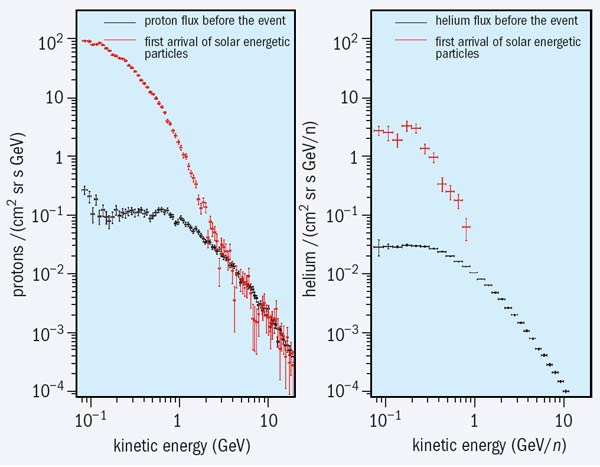

Heavy-ion collisions at all centre-of-mass energies have long been known to display remarkable features of collectivity. In particular, in semicentral heavy-ion collisions at ultra-relativistic energies, approximately twice as many hadrons above pT = 2 GeV are produced parallel to the reaction plane rather than orthogonal to it, giving rise to a characteristic second harmonic v2 in the azimuthal distribution of particle production. Only a month after the end of the first LHC heavy-ion run, the ALICE collaboration announced in December 2010 that this elliptic flow, v2, persists unattenuated from RHIC to LHC energies. The bulk of the up to 1600 charged hadrons produced per unit rapidity in a central Pb–Pb collision at the LHC seems to emerge from the same flow field. Moreover, the strength of this flow field at RHIC and at the LHC is consistent with predictions from fluid-dynamic simulations, in which it emerges from a partonic state of matter with negligible dissipative properties. Indeed, one of the main motivations for a detailed flow phenomenology at RHIC and at the LHC is that flow measurements constrain dissipative QCD transport coefficients that are accessible to first-principle calculations in quantum field theory, thus providing one of the most robust links between fundamental properties of hot QCD matter and heavy-ion phenomenology.

Quark Matter 2011 marks a revolution in the dynamical understanding of flow phenomena in heavy-ion collisions. Until recently, flow phenomenology was based on a simplified event-averaged picture according to which a finite impact parameter collision defines an almond-shaped nuclear overlap region; the collective dynamics then translates the initial spatial asymmetries of this event-averaged overlap into the azimuthal asymmetries of the measured particle-momentum spectra. As a consequence, the symmetries of measured momentum distributions were assumed to reflect the symmetries of event-averaged initial conditions. However, over the past year it has become clear – in an intense interplay of theory and experiment – that there are significant fluctuations in the sampling of the almond-shaped nuclear overlap region on an event-by-event basis. The eventwise propagation of these fluctuations to the final hadron spectra results in characteristic odd flow harmonics, v1, v3, v5, which would be forbidden by the symmetries of an event-averaged spatial distribution at mid-rapidity.

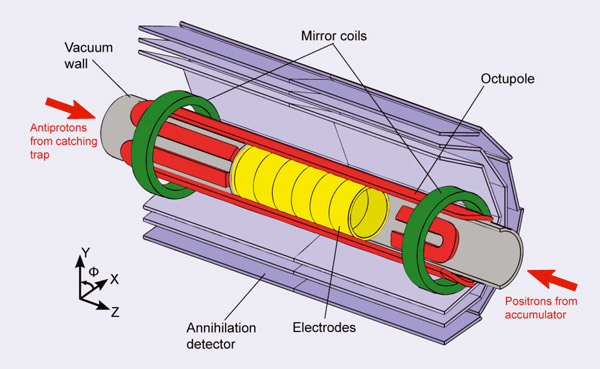

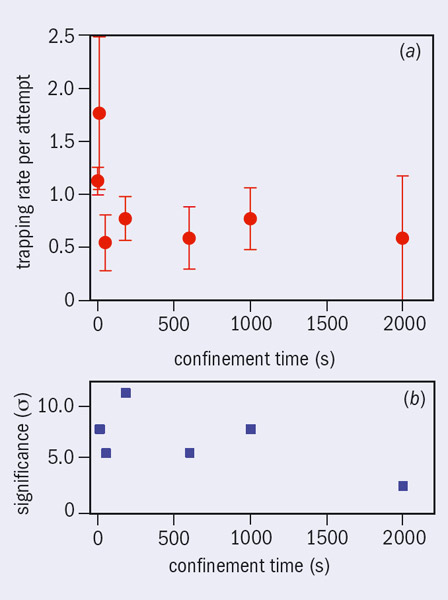

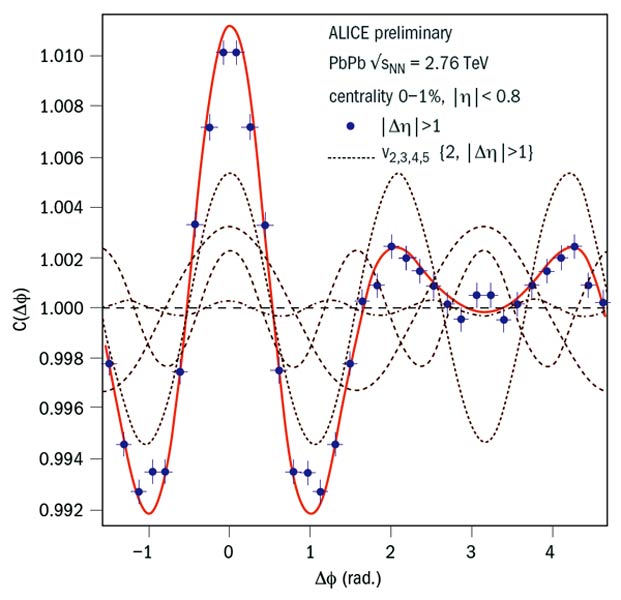

In Annecy, the three LHC experiments and the two at RHIC all showed for the first time flow analyses at mid-rapidity that were not limited to the even flow harmonics v2 and v4; in addition, they indicated sizeable values for the odd harmonics that unambiguously characterize initial-state fluctuations (figure 1). This “Annecy spectrum” of flow harmonics was the subject of two lively plenary debates. The discussion showed that there is already an understanding – both qualitatively and on the basis of first model simulations – of how the characteristic dependence on centrality of the relative size of the measured flow coefficients reflects the interplay between event-by-event initial-state fluctuations and event-averaged collective dynamics.

Several participants remarked on the similarity of this picture with modern cosmology, where the mode distribution of fluctuations of the cosmic microwave background also gives access to the material properties of the physical system under study. The counterpart in heavy-ion collisions may be dubbed “vniscometry”. Indeed, since uncertainties in the initial conditions of heavy-ion collisions were the main bottleneck in using data so far for precise determinations of QCD transport coefficients such as viscosity, the measurement of flow coefficients that are linked unambiguously to fluctuations in the initial state has a strong potential to constrain further the understanding of flow phenomena and the properties of hot strongly interacting matter to which they are sensitive.

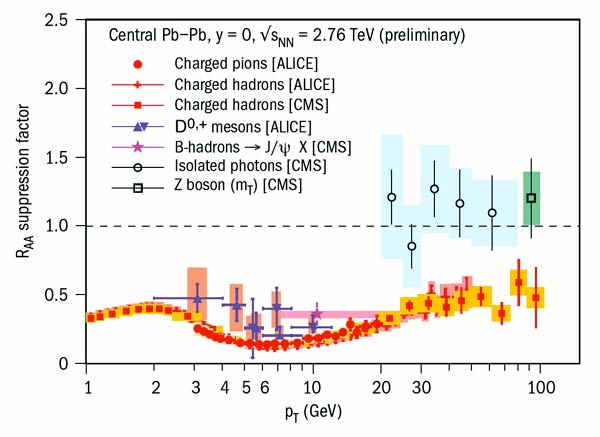

Quark Matter 2011 also featured major qualitative advances in the understanding of high-momentum transfer processes embedded in hot QCD matter. One of the most important early discoveries of the RHIC heavy-ion programme was that hadronic spectra are generically suppressed at high transverse momentum by up to a factor of 5 in the most central collisions. With the much higher rate of hard processes at the tera-electron-volt scale, the first data from ALICE and CMS have already extended knowledge of this nuclear modification of single inclusive hadron spectra up to pT = 100 GeV/c. In the range below 20 GeV/c, these data show a suppression that is slightly stronger but qualitatively consistent with the suppression observed at RHIC. Moreover, the increased accuracy of LHC data allows, for the first time, the identification of a nonvanishing dependence on transverse momentum of the suppression pattern from a factor of around 7 at pT = 6–7 GeV/c to a factor of about 2 at pT = 100 GeV/c, thus adding significant new information.

Another important constraint on understanding high-pT hadron production in dense QCD matter was established by the CMS collaboration with the first preliminary data on Z-boson production in heavy-ion collisions and on isolated photon production at pT up to 100 GeV/c. In contrast to all of the measured hadron spectra, the rate of these electroweakly interacting probes is unmodified in heavy-ion collisions (figure 2). The combination of these data gives strong support to models of parton energy loss in which the rate of hard partonic processes is equivalent to that in proton–proton collisions but the produced partons lose energy in the surrounding dense medium.

The next challenge in understanding high-momentum transfer processes in heavy-ion collisions is to develop a common dynamical framework for understanding the suppression patterns of single inclusive hadron spectra and the medium-induced modifications of reconstructed jets. Already in November 2010, the ATLAS and CMS collaborations reported that di-jet events in heavy-ion collisions show a strong energy asymmetry, consistent with the picture that one of the recoiling jets contains a much lower energy fraction in its jet conical catchment area as a result of medium-induced out-of-cone radiation. At Quark Matter 2011, CMS followed up on these first jet-quenching measurements by showing the first characteristics of the jet fragmentation pattern. Remarkably, these first findings are consistent with a certain self-similarity, according to which jets whose energy was degraded by the medium go on to fragment in the vacuum in a similar fashion to jets of lower energy.

This was the first Quark Matter conference in which data on the nuclear modification factor were discussed in the same session as data on reconstructed jets. All of the speakers agreed in the plenary debate that there will be much more to come. On the experimental side, advances are expected from the increased statistics of future runs, complementary analyses of the intra-jet structure and spectra for identified particles, as well as from a proton–nucleus run at the LHC, which would allow the dominant jet-quenching effect to be disentangled from possibly confounding phenomena. On the theoretical side, speakers emphasized the need to improve the existing Monte-Carlo tools for jet quenching with the aim of constraining quantitatively how properties of the hot and dense QCD matter produced in heavy-ion collisions are reflected in the modifications of hard processes.

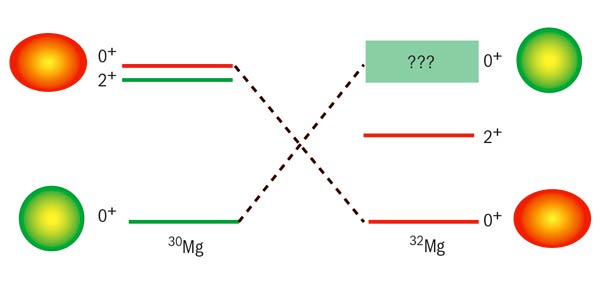

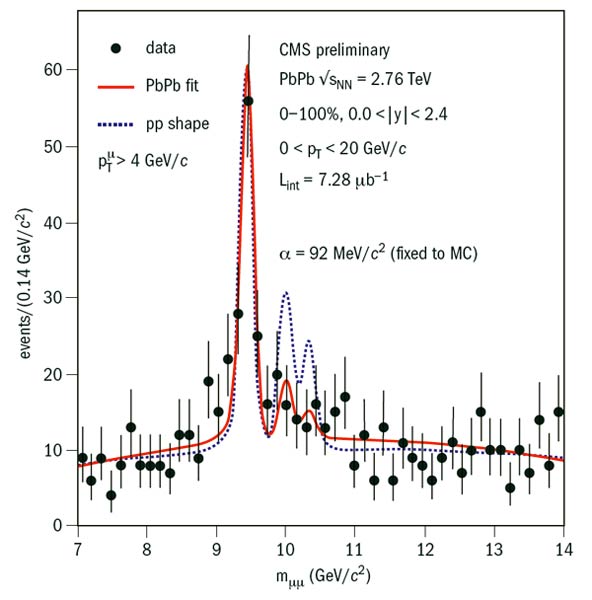

Another highlight of the conference was provided by the first measurements of bottomonium in heavy-ion collisions, reported by the STAR collaboration for gold–gold (Au–Au) collisions at RHIC and the CMS collaboration for Pb–Pb collisions at the LHC. The charmonium and bottomonium families represent a well defined set of Bohr radii that are commensurate with the typical thermal length scales expected in dense QCD matter. On general grounds, it has long been conjectured that, depending on the temperature of the produced matter, the higher excited states of the quarkonium families should melt while the deeper-bound ground states may survive in the dense medium.

While the theoretical formulation of this picture is complicated by confounding factors related to limited understanding of the quarkonium formation process in the vacuum and possible new medium-specific formation mechanisms via coalescence, the CMS collaboration presented preliminary data of the Υ family that are in qualitative support of this idea (figure 3). In particular, CMS has established within statistical uncertainties the absence of higher excited states of the Υ family in the di-muon invariant mass spectrum, while the Υ 1s ground state is clearly observed. The rate of this ground state is reduced by around 40% (suppression factor, RAA = 0.6) in comparison with the yield in proton–proton collisions, consistent with the picture that the feed-down from excited states into this 1s state is stopped in dense QCD matter. STAR also reported a comparable yield. Clearly, this field is now eagerly awaiting LHC operations at higher luminosity to gain a clearer view of the conjectured hierarchy of quarkonium suppression in heavy-ion collisions.

In addition to the scientific programme, Quark Matter 2011 was accompanied by an effort to reach out to the general public. The week before the conference, the well known French science columnist Marie-Odile Monchicourt chaired a public debate between Michel Spiro, president of CERN Council, and Etienne Klein, director of the Laboratoire de Recherches sur les Sciences de la Matière at Saclay and professor of philosophy of science at the Ecole Central de Paris, attracting an audience of around 400 from the Annecy area. During the Quark Matter conference, physicists and the general public attended a performance by actor Alain Carré and the world-famous Annecy-based pianist Francois-René Duchable that merged classical music, literature and artistically transformed pictures from CERN. On another evening, the company Les Salons de Genève performed the play The Physicists, by Swiss writer Friedrich Dürrenmatt, in Annecy’s theatre. While the conference reached out successfully to the general public, participants encountered some problems in reaching out because the wireless in the conference centre turned out to be dysfunctional. However, the highlights were sufficiently numerous to reduce this to a footnote. As one senior member of the community put it during the conference dinner: “It was definitively the best conference since the invention of the internet.”

• For the full programme and videos of Quark Matter 2011, see http://qm2011.in2p3.fr.