Résumé

MedAustron : un projet de coopération inédit

MedAustron, le projet autrichien d’hadronthérapie, est l’aboutissement d’un long travail dans lequel le CERN s’est investi pour créer, par le biais du transfert de technologies, une communauté au service d’un accélérateur. L’article décrit l’évolution du projet : de sa naissance en 1989 après la chute du mur de Berlin, jusqu’aux premiers coups de pioche, il y a quelques mois. Le CERN, associé à toutes les phases du projet, s’est engagé dernièrement dans une étape essentielle : la formation intensive des équipes pour tous les aspects liés à la conception et à la construction de l’accélérateur.

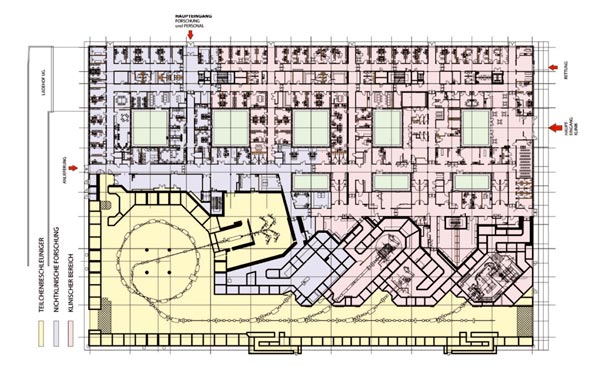

Image credit: Moser Architekten, Vienna.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the subsequent disintegration of the Iron Curtain ended half a century of division for central Europe. Austria moved abruptly from being on the edge of two large political and economic powers to being at the centre of the reviving central European region. Anticipating the potential of the new situation, Meinhard Regler, of the Austrian Academy of Sciences Institute of High Energy Physics (HEPHY), started to campaign for a centre of excellence for scientific research with an international and multidisciplinary character that would stimulate new growth. In the first instance, the exact definition of the facility was left open. Among the possibilities were a synchrotron radiation facility, a centre for microelectronics and a computing centre, but whichever the final choice the aim was to equip the region with a tool for world-class research and to counter the “brain drain” of young scientists.

A commission chaired by Peter Skalicky, the Rector of the Technical University of Vienna, was set up under the patronage of the Austrian Academy of Sciences to study the project, provisionally called AUSTRON, that would fulfil this role. In spring 1991, at a meeting in Bratislava of the “Pentagonale” – a loose co-operation of states instigated by Austria in November 1989, which consisted of Austria, Czechoslovakia, Italy, Hungary and Yugoslavia – the decision was taken that AUSTRON should be a neutron spallation source. In October of that year the idea was developed further and endorsed by a panel of experts representing more than 50 research institutions, during a working week of the “Hexagonale” held at CERN (the addition of Poland to the Pentagonale in 1991 had created the “Hexagonale”, later to become the Central European Initiative).

Neutrons were an attractive proposition. Apart from “ticking all of the boxes”, neutron diagnostics were considered to be reaching a point where their use would increase sharply, as had been the case with synchrotron light some years earlier. There was also the so-called “neutron drought” that the pending closure of many nuclear reactors was likely to trigger. Carlo Rubbia, then CERN’s director-general, strongly encouraged Austria and – because Austria did not have its own accelerator community – he promised the vitally needed technology transfer from CERN’s accelerator experts.

By the end of December 1992, Erhard Busek, then minister for science and research, officially announced the support of the Austrian government. An international scientific advisory board was set up the following year under the chairmanship of Albert Furrer of the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) and a detailed study of the AUSTRON facility took place, hosted by CERN, with the resulting report published in November 1994. Upgrade studies continued into 1998 but sadly the project was faltering and was officially shelved in 2003. It seemed that CERN had lost the chance to stimulate the creation of a new accelerator community in a member state, but the ashes of AUSTRON contained the seed and fertilizer for a second project.

Well before AUSTRON, Robert R Wilson, who was working on cyclotrons at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory (LBL), had written a paper in 1946 in which he proposed using the behaviour of protons at the Bragg peak (where they deposit most of their energy over a short distance at the end of their trajectory) for cancer therapy and in which he even had the foresight to mention carbon ions (CERN Courier December 2006 p24). LBL went on to pioneer hadron therapy, beginning with protons and helium ions and later, after the commissioning of the Bevalac in 1974, work started in earnest with heavier ion species. It continued for about 15 years until the world’s first hospital-based proton treatment centre, Loma Linda, opened in California in 1990. The accelerator equipment for Loma Linda was built with the help of Fermilab and its director – Wilson. In Europe, the first treatment using protons was performed for a cervical cancer in 1957 at the University of Uppsala, which has continued to be a leading proton-based treatment centre.

Seeds for a new project

In 1988, a two-year study for the European Light Ion Medical Accelerator (EULIMA) began to design a European cyclotron for treating deep-seated tumours with 400 MeV/nucleon carbon ions. CERN participated in this study and contributed an alternative design based on a synchrotron. This alternative design, which investigated advanced ideas for gantries and incorporated expertise gained from the Low Energy Antiproton Ring (LEAR) at CERN, firmly set the synchrotron as the preferred machine for light-ion therapy to the present day. This work inspired Regler together with Horst Schönauer at CERN to include a radio-biological facility in the original AUSTRON design study, so providing the seed for a second project.

Image credit: Moser Architekten, Vienna.

Towards the end of the AUSTRON initiative, CERN was under considerable pressure from its own project for the LHC, but there was still a feeling of lost opportunities. Inside AUSTRON, Regler was not ready to give up and was thinking about the medical option, which he called Med-AUSTRON. At the same time, in Italy there was the Terapia con Radiazion Adroniche (TERA) project led by the indefatigable Ugo Amaldi, who was also wondering if CERN could be persuaded to host another study, but this time for a synchrotron for cancer therapy. CERN was particularly well positioned for studying the synchrotron design in view of the extensive R&D that teams there had carried out on slow-extraction schemes in both LEAR and the Proton Synchrotron (PS). These studies ranged from classic quadrupole-driven configurations to exotic ultraslow extractions using stochastic noise. However, it was not a forgone conclusion that CERN would agree in the light of the effort required for the LHC, but the conviction and support of Kurt Hübner, who was then director of accelerators, succeeded in establishing the Proton Ion Medical Machine Study (PIMMS) in the PS Division.

The PIMMS group was formed following an agreement between Med-AUSTRON and the TERA Foundation and was headed by Philip Bryant with expert help from CERN staff. The study group was later joined by Oncology-2000 in the Czech Republic and had a close collaboration with GSI at Darmstadt. The brief was to design a synchrotron-based centre capable of sub-millimetre accuracy for the conformal treatment of complex-shaped tumours by active scanning. Although the centre was to be primarily for carbon ions, protons were to be included. The effort focused first on the theoretical understanding of slow extraction and the techniques to produce a smooth beam-spill. The PIMMS team started work in January 1996 and published their report four years later.

Rise of MedAustron

The acceptance and funding of a project is never a quick process. Unsurprisingly, MedAustron, which had lost its capital letters to stress its independence from AUSTRON, became the subject of a new design study under Thomas Auberger and Erich Griesmayer in Wiener Neustadt, which was published in 2004. By now the weight of the various studies and the excellent proof-of-principle experiments carried out by laboratories such as LBL, GSI and PSI using their own high-energy physics machines, together with the growing involvement of industry, had changed the hadron-therapy landscape. Ion Beam Applications SA in Belgium was already dominating the market for turnkey, cyclotron-based proton facilities and Siemens in Germany was associating with Danfysik in Denmark for the up-and-coming market in carbon-ion machines. Germany was the first European country to fund a carbon-ion centre, with the Heidelberg Ion Therapy Centre; Italy was next with its Centro Nazionale di Adroterapia Oncologica (CNAO) in Pavia; and in 2004 Austria followed suit with the political approval and partial funding of MedAustron (which had now gained an italic front-end) in Wiener Neustadt.

In 2004, the Austrian federal government, the government of Lower Austria and the city of Wiener Neustadt put forward a plan for funding the nonclinical research part of MedAustron and in February 2005, PEG MedAustron GmbH was created under the direction of Theodor Krendelsberger to look after this funding and search for industrial investment partners in a public/private-partnership model for the funding of the medical treatment part. This did not work and the government of Lower Austria stepped forward and assumed the role of the main investor and created the EBG MedAustron GmbH in April 2007 under the direction of Martin Schima and later Bernd Mösslacher to oversee the construction (and future operation) of the facility.

Image credit: Thomas Kästenbauer/Bildreport Austria.

With the conceptual design, funding and business plan in place, the need to formalize the technology transfer for the accelerator design was urgent because Austria had no accelerator community of its own. Discussions with CERN’s director-general at the time, Robert Aymar, and Steve Myers, then Accelerators & Beams Department leader, led to a strategy with three pillars. First, CERN agreed to help by hosting and intensively training the MedAustron team in all aspects of the accelerator design and construction. Second, collaboration agreements were signed with CNAO and PSI, which allowed MedAustron to benefit from the experience of the more advanced Italian project concerning the accelerator complex, as well as from the wealth of knowledge in PSI concerning gantry design and all aspects of medical operation. Some six employees of EBG MedAustron are currently integrated into the PSI activities. Finally, a wider programme of contact and interchanges with strong international partners was set up. This strategy is now well advanced and strongly supported by the current director-general of CERN, Rolf Heuer. Commissioning is expected to start in 2013 and treatments in 2015.

This was not the first time that CERN had hosted a team starting a new facility. In the 1970s, the newly formed European Southern Observatory was given its first home in CERN, followed in the 1980s by the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility. However, in the case of MedAustron, it was the first time that CERN had agreed not only to house a project but also to train the EBG staff by making a CERN staff member, Michael Benedikt, the Technical Project Leader. To date, 35 young engineers have been hired by EBG MedAustron and are working with the experts at CERN to design the MedAustron accelerator complex. The rapid hiring phase was greatly facilitated by the Austrian doctoral student programme, which furnished a third of this intake. Without the doctoral programme, which is funded by the Austrian federal government and has operated in CERN since 1993, it would not have been possible to find so many highly-qualified engineers so quickly.

MedAustron represents the most intensive “head-to-head” transfer of technology that CERN has ever undertaken. In many ways, it is the age-old system of master and apprentice and – as usually happens – the apprentice quickly overtakes the master who looks on proudly.

This is already apparent in the design refinements and new ideas that are being incorporated into the machine. The civil engineering has just started on the site in Wiener Neustadt and in one to two years the young team will fly from the nest at CERN to their new offices. This will be an exciting moment for all involved. For CERN it will mark the first time that an accelerator community has been set up in a member state through technology transfer, surely a reason to celebrate.