The quark model of hadron classification proposed by Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig in 1964 motivated the opinion that a new state of matter, namely strongly interacting matter composed of subhadronic constituents, may exist. Soon thereafter, quantum chromodynamics (QCD) was formulated as the theory of strong interactions, with quarks and gluons as elementary constituents. As a natural consequence, the existence of a state of quasi-free quarks and gluons – the QCD quark–gluon plasma (QGP) – was suggested by Edward Shuryak in 1975. These events, together with the rapid development of particle-accelerator and detector techniques, mark the beginning of the experimental search for this hypothetical, subhadronic form of matter in nature.

First indications

The experimental efforts received a boost from the first acceleration of oxygen and sulphur nuclei at CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) in 1986 (√sNN ≈ 20 GeV) and of lead nuclei in 1994 (√sNN ≈ 17 GeV). Measurements from an array of experiments were surprisingly well described by statistical and hydrodynamical models. They indicated that the created system of strongly interacting particles is close to at least local equilibrium (Heinz and Jacob 2000). Thus, a necessary condition for QGP creation in heavy-ion collisions was found to be fulfilled. The “only” remaining problem was the identification of unique experimental signatures of QGP.

The strategy is clear: look for a rapid change of energy dependence of hadron production properties.

Unfortunately, precise quantitative predictions are currently impossible to calculate within QCD and predictions of phenomenological models suffer from large uncertainties. Therefore, the results of the measurements were only suggestive of the production of QGP in heavy-ion collisions at the top SPS energy. The same situation persisted at the top energies of Brookhaven’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) and seems to be repeated at the LHC. Despite many arguments in favour of the creation of QGP at these energies, its discovery cannot be claimed from these data alone.

A different strategy for identifying the creation of QGP was followed by the NA49 experiment at the SPS and is now being continued by its successor NA61/SHINE, as well as by the STAR experiment at RHIC. The idea is to measure quantities that are sensitive to the state of strongly interacting matter as a function of collision energy in, for example, central lead–lead collisions.

The reasoning is based on simple arguments. First, the energy density of matter created at the early stage of heavy-ion collisions increases monotonically with collision energy. Thus, if two phases of matter exist, the low-energy density phase is created in collisions at low energies and the high-energy density phase in collisions at high energies. Second, the properties of both phases differ significantly, with some of the differences surviving until the freeze-out to hadrons and so can be measured in experiments. The search strategy is therefore clear: look for a rapid change of the energy dependence of hadron production properties that are sensitive to QGP, because these will signal the transition to the new state of matter and indicate its existence.

This strategy, and the corresponding NA49 energy-scan programme, were motivated in particular by a statistical model of the early stage of nucleus–nucleus collisions (Gazdzicki and Gorenstein 1999). It predicted that the onset of deconfinement should lead to rapid changes of the collision-energy dependence of bulk properties of produced hadrons, all appearing in a common energy domain. Data from 1999 to 2002 on central Pb+Pb collisions at 20A, 30A, 40A, 80A and 158A GeV were recorded and the predicted features were observed at low SPS energies.

An independent verification of NA49’s discovery is vital and calls for further measurements in the SPS energy range. Two new experimental programmes are already in operation: the ion programme of NA61/SHINE at the SPS; and the beam-energy scan at RHIC. Elsewhere, the construction of the Nuclotron-based Ion Collider at JINR, Dubna, is in preparation. The basic goals of this experimental effort are the confirmation and the study of the details of the onset of deconfinement and the investigation of the transition line between the two phases of strongly interacting matter. In particular, the discovery of the hypothesized second-order critical end-point would be a milestone in uncovering properties of strongly interacting matter.

Four pointers

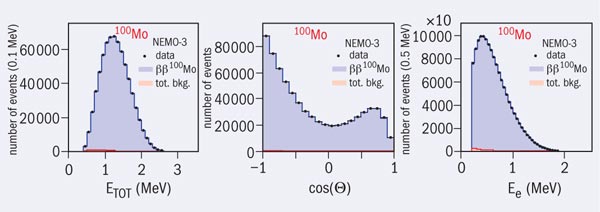

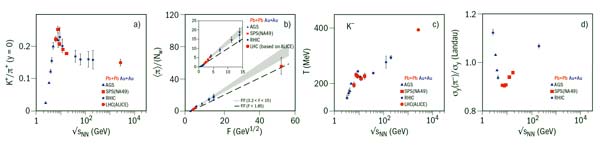

Last year rich data from the RHIC beam-energy scan programme were released (Kumar 2011, Mohanty 2011). Furthermore, the first results from Pb+Pb collisions at the LHC were revealed (Schukraft et al. 2011, Toia et al. 2011). It is therefore time to review the status of the observation of the onset of deconfinement. The plots in figure 1 summarize relevant results that became available in June 2011. They show the energy dependence of four hadron-production properties measured in central Pb+Pb (Au+Au) collisions, which reveal structures referred to as the “horn”, “kink”, “step” and “dale” – all located in the SPS energy range.

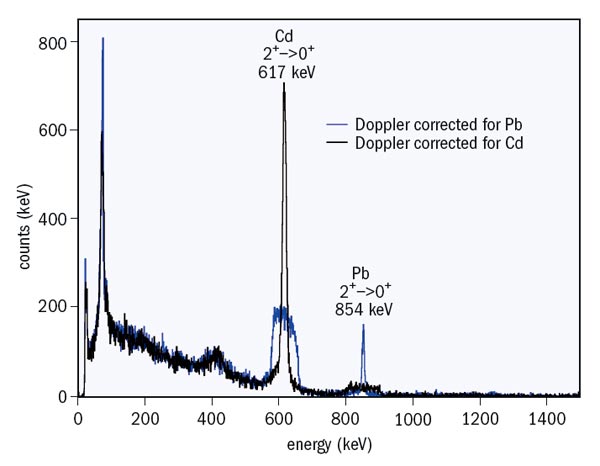

The horn. The most dramatic change of the energy dependence is seen for the ratio of yields of kaons and pions (figure 1a). The steep threshold rise of the ratio characteristic for confined matter changes at high energy into a constant value at the level expected for deconfined matter. In the transition region (at low SPS energies) a sharp maximum is observed, caused by the higher production ratio of strangeness-to-entropy in confined matter than in deconfined matter.

The kink. Most particles produced in high-energy interactions are pions. Thus, pions carry basic information on the entropy created in the collisions. On the other hand, entropy production depends on the form of matter present at the early stage of collisions. Deconfined matter is expected to lead to a final state with higher entropy than confined matter. Consequently, the entropy increase at the onset of deconfinement is expected to lead to a steeper increase with collision energy of the pion yield per participating nucleon. This effect is observed for central Pb+Pb collisions (figure 1b). When passing through low SPS energies, the slope of the rise in the ratio <π>/<NP> with the Fermi energy measure F ≈ √√sNN increases by a factor of about 1.3. Within the statistical model of the early stage, this corresponds to an increase of the effective number of degrees of freedom by a factor of about 3.

The step. The experimental results on the energy dependence of the inverse slope parameter, T, of K– transverse-mass spectra for central Pb+Pb (Au+Au) collisions are shown in figure 1c. The striking features of these data can be summarized and interpreted as follows (Gorenstein et al. 2003). The T parameter increases strongly with collision energy up to low SPS energies, where the creation of confined matter at the early stage of the collisions takes place. In a pure phase, increasing collision energy leads to an increase of the early-stage temperature and pressure. Consequently the transverse momenta of produced hadrons, measured by the inverse slope parameter, increase with collision energy. This rise is followed by a region of approximately constant value of the T parameter in the SPS energy range, where the transition between confined and deconfined matter with the creation of a mixed phase is located. The resulting softening of the equation of state “suppresses” the hydrodynamical transverse expansion and leads to the observed plateau or even a minimum structure in the energy dependence of the T parameter. At higher energies (RHIC data), T again increases with collision energy. The equation of state at the early stage again becomes stiff and the early-stage pressure increases with collision energy, resulting in a resumed increase of T.

The dale. As discussed above, a weakening of the transverse expansion is expected to result from the onset of deconfinement because of the softening of the equation of state at the early stage. Clearly, the latter should also weaken the longitudinal expansion (Petersen and Bleicher 2006). This expectation is confirmed in figure 1d, where the width of the π– rapidity spectra in central Pb+Pb collisions relative to the prediction of ideal Landau hydrodynamics is plotted as a function of the collision energy. In fact, the ratio has a clear minimum at low SPS energies.

A smooth evolution is observed between the top SPS energy and the current energy of the LHC.

The results shown in figure 1 include new results on central Pb+Pb collisions at the LHC and data on central Au+Au collisions from the RHIC beam-energy scan. The RHIC results confirm the NA49 measurements at the onset energies while the LHC data demonstrate that the energy dependence of hadron-production properties shows rapid changes only at low SPS energies. A smooth evolution is observed between the top SPS energy (17.2 GeV) and the current energy of the LHC (2.76 TeV). This strongly supports the interpretation of the NA49 structures as arising from the onset of deconfinement. Above the onset energy only a smooth change of the QGP properties with increasing collision energy is expected.

The first LHC data thus confirm the following expected effects:

• an approximate energy independence of the K+/π+ ratio above the top SPS energy (figure 1a);

• a linear increase of the pion yield per participant with F ≈ √√sNN with the slope defined by the top SPS data (figure 1b);

• a monotonic increase of the kaon inverse-slope parameter with energy above the top SPS energy (figure 1c).

The width of the π– rapidity spectra in central Pb+Pb collisions should increase continuously from the top SPS energies to the LHC energies, as predicted by ideal gas Landau hydrodynamics. LHC data on rapidity spectra are required to verify this expectation.

The NA61/SHINE experiment

The confirmation of the NA49 measurements and their interpretation in terms of the onset of deconfinement by the new LHC and RHIC data strengthen the arguments for the NA61/SHINE experiment, which will use secondary proton and Be, as well as primary Ar and Xe beams in the SPS beam momentum range (13A–158A GeV/c). The basic components of the NA61 detector were inherited from NA49. Several important upgrades – in particular, the new and faster read-out of the time-projection chambers, the new, state-of-the-art resolution Projectile Spectator Detector and the installation of background-reducing helium beam pipes – allow the collection of data of high statistical and systematic accuracy. In parallel to the ion programme, the NA61/SHINE experiment is also making precision measurements of hadron production in proton- and pion-nucleus collisions for the Pierre Auger Observatory’s studies of cosmic rays and the T2K long-baseline neutrino experiment.

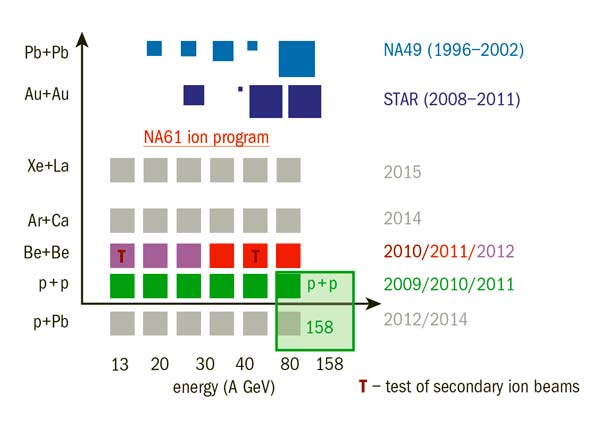

NA61 has already begun a two-dimensional scan in collision energy and the size of the colliding nuclei (figure 2). Data on proton–proton interactions at six collision energies were recorded in 2009–2011 and a successful test of secondary ion beams took place in 2010. The first physics run with secondary Be beams came in November/December 2011. Most important for the programme are runs with primary Ar and Xe beams, expected for 2014 and 2015, respectively. The collaboration between CERN and the iThemba Laboratory in South Africa is ensuring a timely optimization of the ion-source parameters. This all adds up to a future where the results from NA61 will allow a detailed study of the properties of the onset of deconfinement and a systematic search for the critical point of strongly interacting matter.