Tuesday 13 December 2011 is a day that many will remember. There was high anticipation of what the ATLAS and CMS collaborations would have to say about the latest results on the search for the elusive Higgs boson. Only senior management knew what the other collaboration was going to present, for the rest it was a well kept surprise.

From 8.30 a.m. onwards, physicists flocked into the main auditorium at CERN and by 10.30 a.m. the place was packed – three and a half hours before the talks even started – and no more people were being allowed in. The atmosphere was almost festive, maybe because the wireless network became saturated so that nobody could work. Similarly eager anticipation could be felt in a separate room where journalists representing the many news agencies and TV channels were able to share in the excitement.

But what was all of the excitement about?

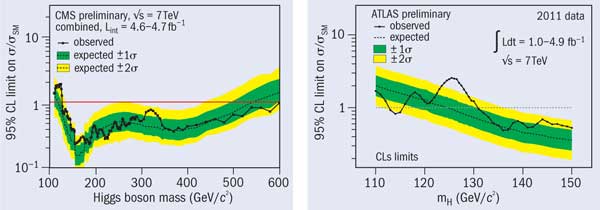

The short answer is that the presentations revealed that if the Higgs boson exists in the manner predicted by the Standard Model, then its mass is most likely between 115.5 and 127 GeV. To be more precise, the CMS collaboration rules out at 95% confidence level a Higgs boson with a mass larger than 127 GeV, while the ATLAS collaboration rules it out for masses below 115.5 GeV and larger than 131 GeV (with a small window of 237–251 GeV in mass not yet excluded by ATLAS). The upper limits on the exclusion region are 468 GeV for ATLAS and 600 GeV for CMS.

The ability to exclude the low-mass region was limited in both experiments by an excess of events around 120 GeV.

The ability to exclude the low-mass region was limited in both experiments by an excess of events around 120 GeV. Such excesses could be just background fluctuations or the first indications of a Higgs signal building up. These results are consistent with what is expected from the statistics accumulated so far, whether the low-mass Higgs exists or not.

The 2012 data campaign, during which the LHC is expected to deliver at least twice as many collisions as in 2011, should put to rest the 40-year quest for the Standard Model Higgs boson via either its discovery or its complete exclusion.

Only a month after the end of proton–proton collisions in 2011, both collaborations showed preliminary results using the full statistics of the year, corresponding to an integrated luminosity of 4.6–4.9 fb–1 – almost twice that shown at the summer conferences. The results unveiled in the presentations in December demonstrate the deep understanding achieved by each collaboration of detector performance and of the numerous backgrounds.

Both spokespeople, Fabiola Gianotti for the ATLAS collaboration and Guido Tonelli for the CMS collaboration, paid tribute in their presentations to the hundreds of physicists – most of them students and young post-docs – who have worked so hard in recent months to improve substantially the understanding of the detectors, in particular under the complex condition of ever increasing pile-up, where as many as 20 interaction vertices were reconstructed in a single event.

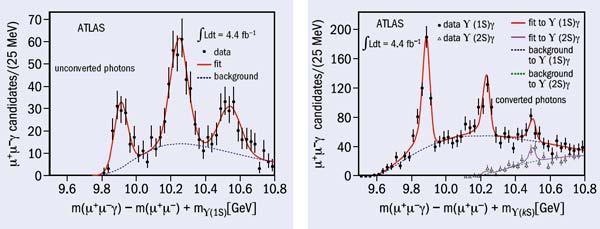

As a result of a coin toss by the director-general, Gianotti spoke first. The ATLAS collaboration had concentrated on updating the analyses in the channels that are most sensitive to the low-mass Higgs boson: H→γγ and the “golden channel”, H→ZZ→llll, where l indicates an electron or a muon. An update of the H→WW search with the data collected for the summer conferences was also shown. While in the first two channels the Higgs boson would be seen as a narrow peak on top of a broad background, the presence of the Higgs boson in the third channel would be seen as a more broad excess of events.

Tonelli then took the stage and presented a full array of CMS analyses – all including the full 2011 statistics – starting with the ones sensitive to the highest Higgs masses, H→ZZ →(llqq), (llνν), (llττ), continuing with H→WW, H→ττ, H→bb and finishing with H→γγ and the golden channel H→ZZ→ llll.

The energy and angular resolutions of the electromagnetic calorimeters are the key ingredients in the analysis of H→γγ, which is potentially the single-most sensitive mode in the low-mass region. The better the resolution, the narrower the peak in the invariant-mass distribution of the two photons and the easier it will be to see the Higgs, if it exists.

Despite having two different detector technologies – ATLAS uses a liquid argon sampling calorimeter, while CMS relies on crystals – the mass resolution obtained in both experiments in the channel with the best resolution is 1.4 GeV. For CMS, good mass resolution is possible thanks in particular to the major progress that has been achieved in understanding the calibration of the crystal calorimeter; in the central area of the calorimeter the performance is now close to nominal. The ATLAS calorimeter provides a similar mass resolution to that of CMS, despite intrinsically worse energy resolution. This is thanks to its capability to measure photon angles.

To explore all our coverage marking the 10th anniversary of the discovery of the Higgs boson ...