Particle physicists – like many other scientists – are used to working under well controlled laboratory conditions, with constant temperature, controlled humidity and perhaps even a clean-room environment. They would consider crazy anyone who tried to install an experiment in the field outside the lab environment, without shelter against wind and weather. So what must they think of a group of physicists and engineers planning to install a huge, highly complex detector on the bottom of the open sea?

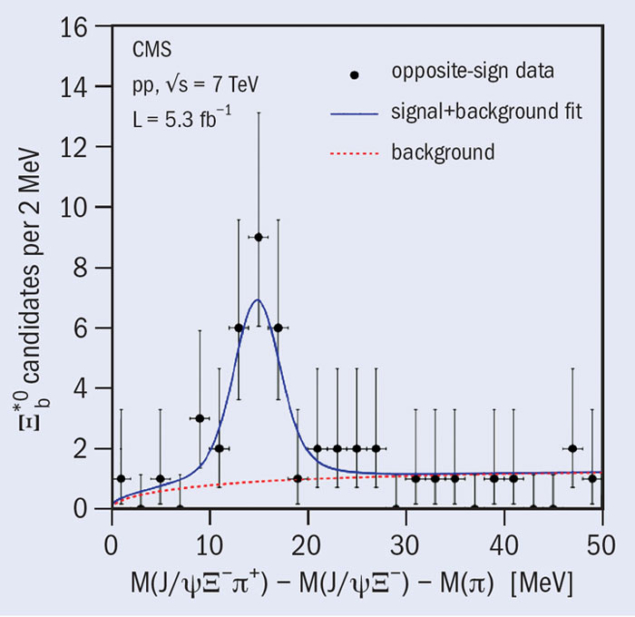

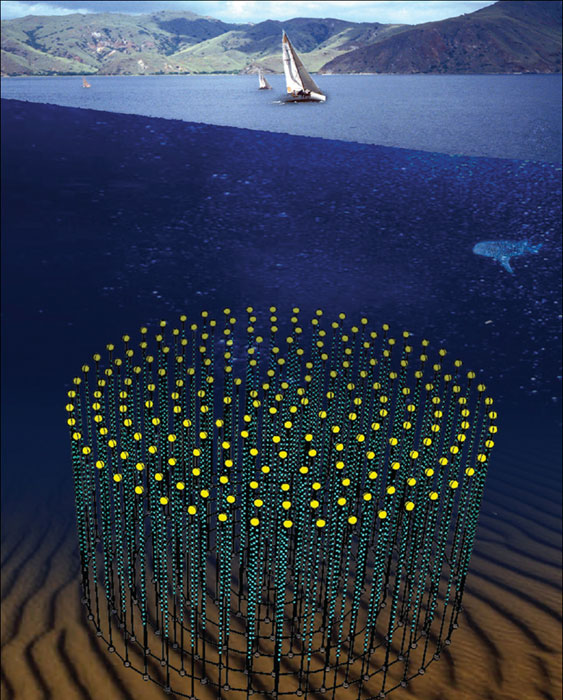

This is exactly what the KM3NeT project is about: a neutrino telescope that will consist of an array of photo-sensors instrumenting several cubic kilometres of water deep in the Mediterranean Sea (figure 1). The aim is to detect the faint Cherenkov light produced as charged particles emerge from the reactions of high-energy neutrinos in the instrumented volume of ocean or the rock beneath it. Most of the neutrinos that are detected will be “atmospheric neutrinos”, originating from the interactions of charged cosmic rays in the Earth’s atmosphere. Hiding among these events will be a few that have been induced by neutrinos of cosmic origin, and these are the prime objects that the experimenters desire.

Ideal messengers

Why are a few cosmic neutrinos worth the huge effort to construct and operate such an instrument? A century after the discovery of cosmic rays, the start of construction of the KM3NeT neutrino telescope marks a big step forwards in understanding their origin and solving the mystery of the astrophysical processes in which they acquire energies that are many orders of magnitude beyond the reach of terrestrial particle accelerators. This is because neutrinos are ideal messengers from the universe: they are neither absorbed nor deflected, i.e. they can escape from dense environments that would absorb all other particles; they point back to their origin; and they are produced inevitably if protons or heavier nuclei with the energies typical of cosmic rays – up to eight orders of magnitude above the LHC beam energy – scatter on other nuclei or on photons and thereby signal astrophysical acceleration of nuclei.

Only a handful of neutrinos assigned to an astrophysical source would convey the unambiguous message that this source accelerates nuclei – a finding that can not be achieved any other way. Of course, much more can be studied with neutrino telescopes. Cosmic neutrinos might signal annihilations of dark-matter particles, and their isotropic flux provides information about sources that cannot be resolved individually. Moreover, atmospheric neutrinos could be used to make measurements of unique importance for particle physics, such as the determination of the neutrino-mass hierarchy.

Driven by the fundamental significance of neutrino astronomy, a first generation of neutrino telescopes with instrumented volumes up to about a per cent of a cubic kilometre was constructed over the past two decades: Baikal, in the homonymous lake in Siberia; AMANDA, in the deep ice at the South Pole; and ANTARES, off the French Mediterranean coast. These detectors have proved the feasibility of neutrino detection in the respective media and provided a wealth of experience on which to build. However, they have not – yet – identified any neutrinos of cosmic origin.

These results and the evolution of astrophysical models of potential classes of neutrino sources over the past few years indicate that, in fact, much larger target volumes are necessary for neutrino astronomy. The first neutrino telescope of cubic-kilometre size, the IceCube observatory at the South Pole, was completed in December 2010. Its integrated exposure is growing rapidly and the discovery of a first source may be just round the corner.

Why then start constructing another large neutrino telescope? Would it not be better to wait and see what IceCube finds? To answer this question it is important to understand in somewhat more detail the way in which neutrinos are actually measured.

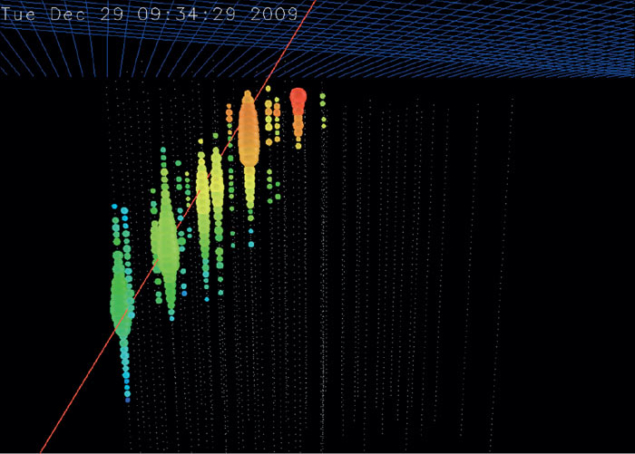

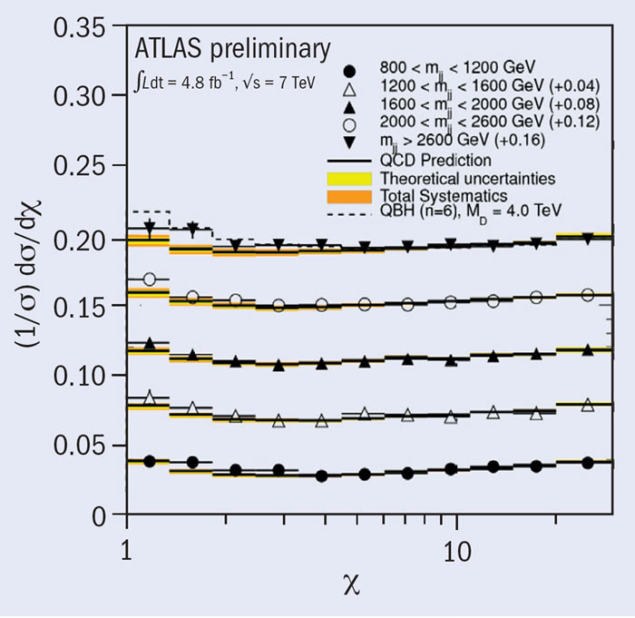

The key reaction is the charged-current (mostly deep-inelastic) scattering of a muon-neutrino or muon-antineutrino on a target nucleus. In such a reaction, an outgoing muon is produced that, on average, carries a large fraction of the neutrino energy and is emitted with only a small angular deflection from the neutrino direction. The muon trajectory – and thus the neutrino direction – is reconstructed from the arrival times of the Cherenkov light in the photo-sensors and the positions of the sensors. This method is suitable for the identification of neutrinos if they come from the opposite hemisphere, i.e. through the Earth. If they come from above, then the resulting muons are barely distinguishable from “atmospheric” muons that penetrate to the detector and are much more numerous. Neutrino telescopes therefore look predominantly “downwards” and do not cover the full sky. IceCube, being at the South Pole, can thus observe the Northern sky but not the Galactic centre and the largest part of the Galactic plane (figure 2).

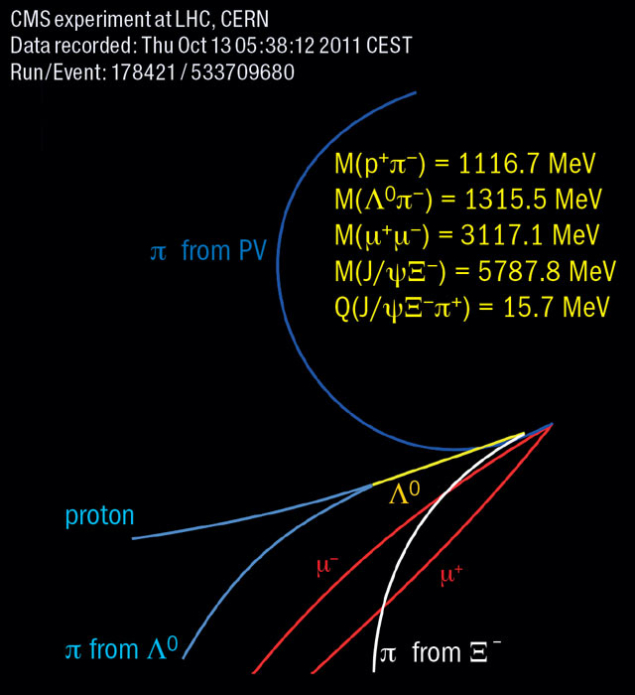

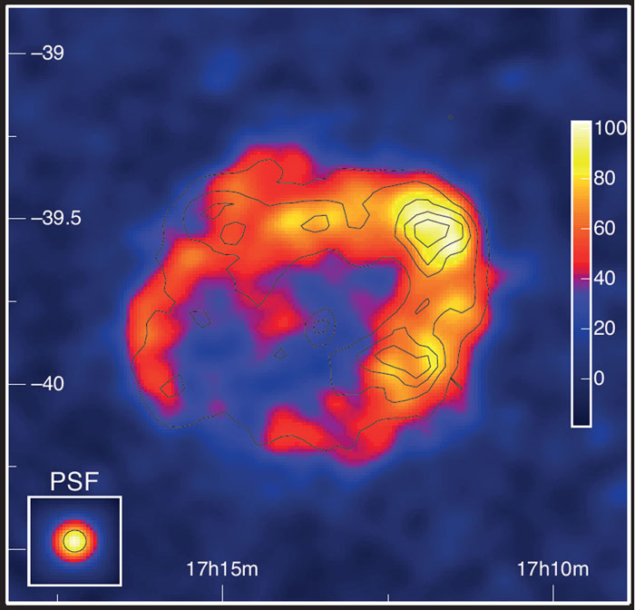

The KM3NeT telescope will have the Galactic centre and central plane of the Galaxy in its field of view and will be optimized to discover and investigate the neutrino flux from Galactic sources. Shell-type supernova remnants are a particularly interesting kind of candidate source. In these objects the supernova ejecta hit interstellar material, such as molecular clouds, and form shock fronts. Gamma-ray observations show that these are places where particles are accelerated to very high energies – but there is an intense debate as to whether these gamma rays stem from accelerated electrons and positrons or hadrons. The only way to give a conclusive answer is through observing neutrinos. Figure 3 shows the sensitivity of KM3NeT and other different experiments to neutrino point sources. According to simulations based on model calculations using gamma-ray measurements by the High Energy Stereoscopic System (HESS) – an air Cherenkov telescope – KM3NeT could make an observation of the supernova remnant RX J1713.7-3946 (figure 4) with a significance of 5σ within 5 years, if the emission process is purely hadronic.

The construction of a neutrino telescope of this sensitivity within a realistic budget faces a number of challenges. The components have to withstand the hostile environment with several hundred bar of static pressure and extremely aggressive salt water. That limits the choice of materials, in particular as maintenance is difficult or even impossible. In addition, background light from the radioactive decay of potassium-40 and bioluminescence causes high rates of photomultiplier hits, while the deployment of the detector requires tricky sea operations and the use of unmanned submersibles to make cable connections.

When the KM3NeT design effort started out with an EU-funded Design Study (2006–2009), a target cost of €200 million for a cubic-kilometre detector was defined. At the time, this was considered utterly optimistic in view of the investment cost for ANTARES of about €20 million. Now, in 2012, the collaboration is confident that it can construct a detector of 5–6 km3 for €220–250 million. This enormous development is partly a result of optimizing the neutrino telescope for slightly higher energies, which implies larger horizontal and vertical distances between the photo-sensors. The main progress, however, has been in the technical design. Almost all of the components have been newly designed, in many cases pursuing completely new approaches.

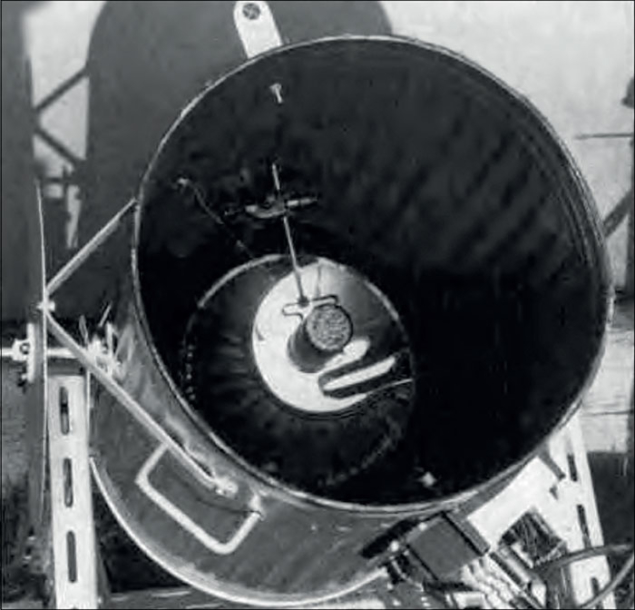

The design of the optical module is a prime example. Instead of a large, hemispherical photomultiplier (8- or 10-inch diameter) in a glass sphere (17-inch diameter), the design now uses as many as 31 photomultipliers of 3-inch diameter per sphere (figure 5). This triples the photocathode area for each optical module, allows for a clean separation of hits with one or two photo-electrons and adds some directional sensitivity.

All data, i.e. all photomultiplier hits, will be digitized in the optical modules and sent to shore via optical fibres. At the shore station, a data filter will run on a computer cluster and select the hit combinations in which the hit pattern and timing are compatible with particle-induced events.

Three countries (France, Italy and the Netherlands) have committed major contributions to an overall funding of €40 million for a first construction phase; others (Germany, Greece, Romania and Spain) are contributing at a smaller level or have not yet made final decisions. It is expected that final prototyping and validation activities will be concluded by 2013 and that construction will begin in 2013–2014. The installation will soon substantially exceed any existing northern-hemisphere instruments in sensitivity, thus providing discovery potential from an early stage.

Last, astroparticle physicists are not alone in looking forward to KM3NeT. For scientists from various areas of underwater research, the detectors will provide access to long-term, continuous measurements in the deep sea. It will provide nodes in a global network of deep-ocean observatories and thus be a truly multidisciplinary research infrastructure.

• For more information, see the KM3NeT Technical Design Report at www.km3net.org.