On 18 May, the US Department of Energy’s Jefferson Lab shut down its Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF) after a long and highly successful 17-year run, which saw the completion of more than 175 experiments in the exploration of the nature of matter. At 8.17 a.m., Jefferson Lab’s director, Hugh Montgomery, terminated the last 6 GeV beam and Accelerator Division associate director, Andrew Hutton, and director of operations, Arne Freyberger, threw the switches on the superconducting RF zones that power CEBAF’s two linear accelerators. Coming up next – the return of CEBAF, with double the energy and a host of other enhancements designed to delve even deeper into the structure of matter.Jefferson Lab has been preparing for its 12 GeV upgrade of CEBAF for more than a decade. In fact, discussions of CEBAF’s upgrade potential began soon after it became the first large-scale accelerator built with superconducting RF technology. Its unique design features two sections of superconducting linear accelerator, which are joined by magnetic arcs to enable acceleration of a continuous-wave electron beam by multiple passes through the linacs. The final layout took account of CEBAF’s future, allowing extra space for an expansion.

Designed originally as a 4 GeV machine, CEBAF exceeded that target by half as much again to deliver high-luminosity, continuous-wave electron beams at more than 6 GeV to targets in three experimental halls simultaneously. Each beam was fully independent in current, with a dynamic range from picoamps to hundreds of microamps. Exploiting the new technology of gallium-arsenide strained-layer photocathodes provided beam polarizations topping 85%, with sufficient quality for parity-violation experiments.

Inside the nucleon

CEBAF began serving experiments in 1995, bombarding nuclei with the 4 GeV electron beam. Its physics reach soon far outstripped the initial planned experimental programme, which was historically classified in three broad categories: the structure of the nuclear building blocks; the structure of nuclei; and tests of fundamental symmetry.

Experiments exploring the structure of the proton led to the discovery that its magnetic distribution is more compact than its charge. This surprising result, which contradicted previous data, generated many spin-off experiments and caused a renewed interest in the basic structure of the proton. Other studies confirmed the concept of quark–hadron duality, reinforcing the predicted relationship between these two descriptions of nucleon structure. Other measurements found that the contribution of strange quarks to the properties of the proton is small, which was also something of a surprise.

Turning to the neutron, CEBAF’s experiments made groundbreaking measurements of the distribution of electric charge, which revealed that up quarks congregate towards the centre, with down quarks converging along the periphery. Precision measurements were also made of the neutron’s spin structure for the first time, as Jefferson Lab demonstrated the power of its highly polarized deuteron target and polarized helium-3 target.

Studies conducted with CEBAF revealed new information about the structure of the nucleon in terms of quark flavour, while others measured the excited states of the nucleon and found new states that were long predicted in quark models of the nucleon. High-precision data on the Δ resonance – the first excited state of the proton – demonstrated that its formation is not described by perturbative QCD, as some theorists had proposed. Researchers also used CEBAF to make precise measurements of the charged pion form-factor to probe its distribution of electric charge. New measurements of the lifetime of the neutral pion were also performed to test the low-energy effective field theory of QCD.

Following the development of generalized parton distributions (GPDs), a novel framework for studying nucleon structure, CEBAF provided an early experimental demonstration that they can be measured using high-luminosity electron beams. Following the upgrade, it will be possible to make measurements that can combine GPDs with transverse momentum distribution functions to provide 3D representations of nucleon structure.

From nucleons to nuclei

In its explorations of the structure of nuclei, research with CEBAF bridges the descriptions of nuclear structure from experiments that show the nucleus built of protons and neutrons to those that show the nucleus as being built of quarks. The first high-precision determination of the distribution of charge inside the deuteron (built of one proton and one neutron) at short distances revealed information about how the deuteron’s charge and magnetization – terms related to its quark structure – are arranged.

Systematic deep-inelastic experiments with CEBAF have shed light on the EMC effect. Discovered by the European Muon collaboration at CERN, this is an unexpected dip in per-nucleon cross-section ratios of heavy-to-light nuclei, which indicates that the quark distributions in heavy nuclei are not simply the sum of those of the constituent protons and neutrons. The CEBAF studies indicated that the effect could be generated by high-density local clusters of nucleons in the nucleus, rather than by the average density.

Related studies provided experimental evidence of nucleons that move so close together in the nucleus that they overlap, with their quarks and gluons interacting with each other in nucleon short-range correlations. Further explorations revealed that neutron–proton short-range correlations are 20 times more common than proton–proton short-range correlations. New experiments planned for the upgraded CEBAF will further probe the interactions of protons, neutrons, quarks and gluons to improve understanding of the origin of the nucleon–nucleon force.

High-precision data from CEBAF are also helping researchers to probe nuclei in other ways. Hypernuclear spectroscopy, which exploits the “strangeness” degree of freedom by introducing a strange quark into nucleons and nuclei, is being used to study the structure and properties of baryons in the nucleus, as well as the structure of nuclei. Also, the recent measurement of the “neutron skin” of lead using parity-violation techniques will be used to constrain the calculations of the fate of neutron stars.

CEBAF’s highly polarized, high-luminosity, highly stable electron beams have exhibited excellent quality in energy and position. Coupled with the state-of-the-art cryotargets and large-acceptance precision detectors, this has allowed exploration of physics beyond the Standard Model through parity-violating electron-scattering experiments. Currently, the teams are eagerly awaiting the results of analysis of the experimental determination of the weak charge of the proton.

A bright future

Although the era of CEBAF at 6 GeV is over, the future is still bright. Jefferson Lab’s Users Group has swelled to more than 1350 physicists. They are eager to take advantage of the upgraded CEBAF when it comes back online, with 52 experiments – totalling some six years of beam time – already approved by the laboratory’s Program Advisory Committee (Dudek et al. 2012).

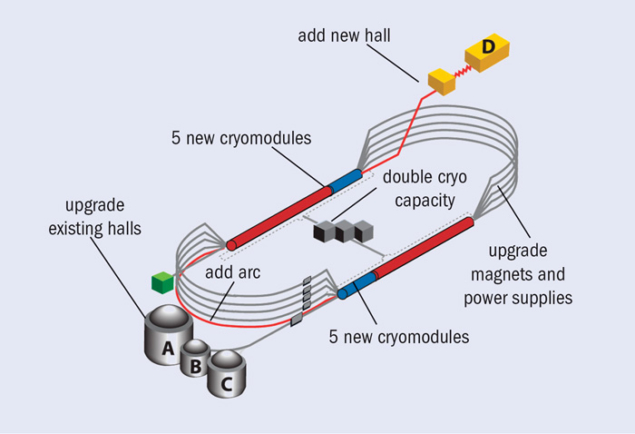

Jefferson Lab is now shut down for installation of the new and upgraded components that are needed to finish the 12 GeV project. At a cost of $310 million, this will enhance the research capabilities of the CEBAF accelerator by doubling its energy and adding an additional experimental hall, as well as by improving the existing halls along with other upgrades and additions.

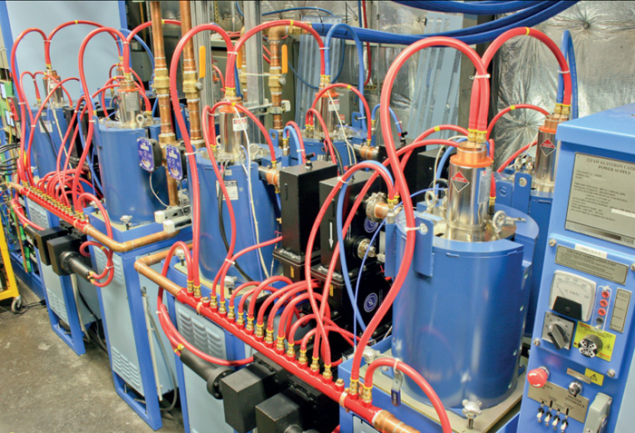

Preliminary commissioning of an upgrade cryomodule has demonstrated good results. The unit was installed in 2011 and commissioned with a new RF system during CEBAF’s final months of running at 6 GeV. The cryomodule successfully ran at its full specification gradient, 108 MeV, for more than an hour while delivering beam to two experimental halls. Commissioning of the 12 GeV machine is scheduled to commence in November 2013. Beam will be directed first to Hall A and its existing spectrometers, followed by the new experimental facility, Hall D.