The unusually early date for the 20th International Workshop on Deep-Inelastic Scattering and Related Subjects proved not to be a problem. The trees were all in blossom in Bonn during DIS 2012, which was held there on 26–30 March, and the sun shone for most of the week. As is the tradition for these workshops, the first day consisted of plenary talks, with the ensuing three days devoted to parallel sessions, followed by a final day of summary talks from the seven working groups. Almost all of the 300 participants also gave talks: there were as many as 275 contributions, not including the summaries. For the first time, the number of results from the LHC experiments at CERN was larger than from DESY’s HERA collider, which shut down in 2007. Given such a large number of contributions, it is not possible to do justice to them all, so the following report presents only a few rather subjective highlights.

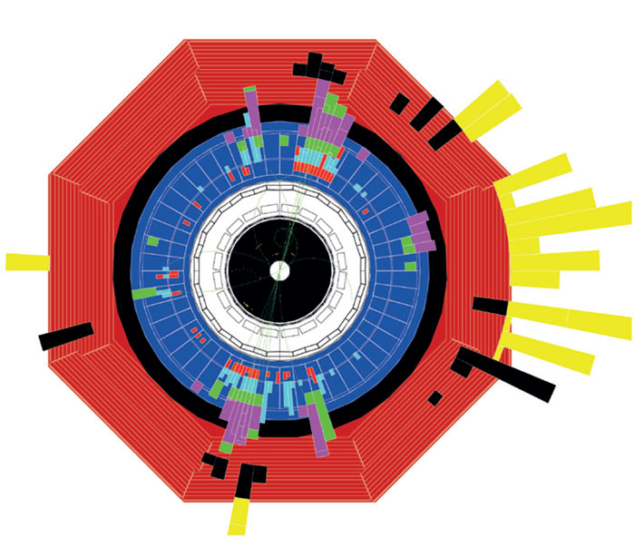

With the move from dominantly electron–proton collisions to more and more results coming from hadron colliders, the workshop started with an “Introduction to deep-inelastic scattering: past and present” by Joël Feltesse of IRFU/CEA/Saclay. Talks on theory and on experiment followed, which covered the full breadth of the topics presented in more detail in the parallel sessions. With running at Fermilab’s Tevatron coming to an end in 2011, results with the complete data set are now being released by the CDF and DØ collaborations. There were also several results from the LHC experiments based on the complete data set for 2011. The emphasis in many of the theory presentations was on calculating processes to higher orders and on parton density function (PDF) and scale uncertainties.

Structure functions and PDFs

Measurements that are relevant to the determination of the PDFs in the nucleon, were reported on combined data from the HERA experiments, H1 and ZEUS, the LHC experiments, ATLAS, CMS and LHCb, as well as from the Tevatron experiments, CDF and DØ. New experimental results have come – in particular from the LHC – on Drell-Yan production, including W and Z bosons, and from HERA and the LHC on jet production, including jets with heavy flavour. In addition, analyses of deep-inelastic scattering (DIS) data on nuclei were presented at the workshop.

There has been substantial progress in the development of tools for PDF fitting

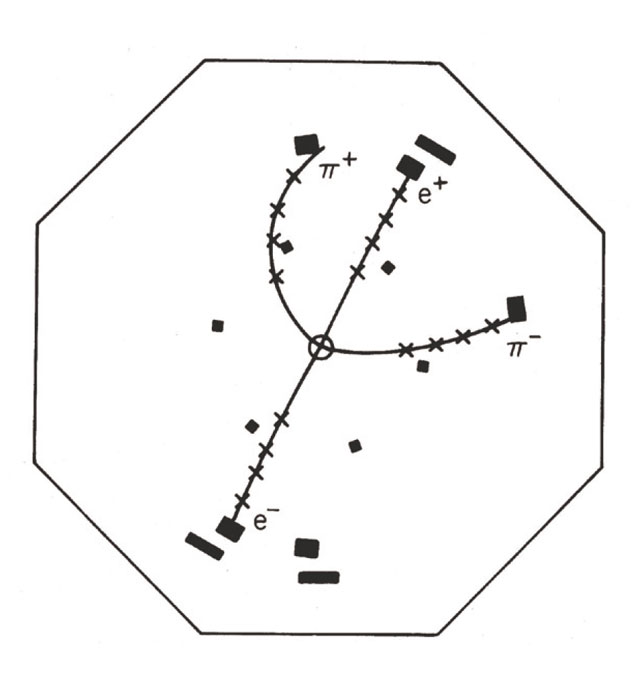

There has been substantial progress in the development of tools for PDF fitting, including the so-called HERAfitter package. This package is designed to include all types of data in a global fit and can be used by both experimentalists and theorists to compare different theoretical approaches within a single framework. The FastNLO package can calculate next-to-leading-order (NLO) jet cross-sections on grids that can then be used for comparisons of data and theory, as well as in PDF fitting. Figure 1 shows a comparison of data and theory for many different energies and processes.

Looking at the current status of fit results, the conclusion is that the determination of the PDFs still gives rise to some controversy but that there is progress in understanding the differences, as Amanda Cooper-Sarkar of Oxford University explained. All of the groups presented PDFs up to next-to-next-to-leading order (NNLO) in the Dokshitzer-Gribov-Lipatov-Altarelli-Parisi formalism. Extensions of the formalism into the Balitsky-Fadin-Kuraev-Lipatov regime and into the high-density regime of nuclei are in progress. The H1 and ZEUS collaborations have also measured the longitudinal structure function, FL. However, the precision is still not good enough to discriminate between predictions of the gluon density and different models.

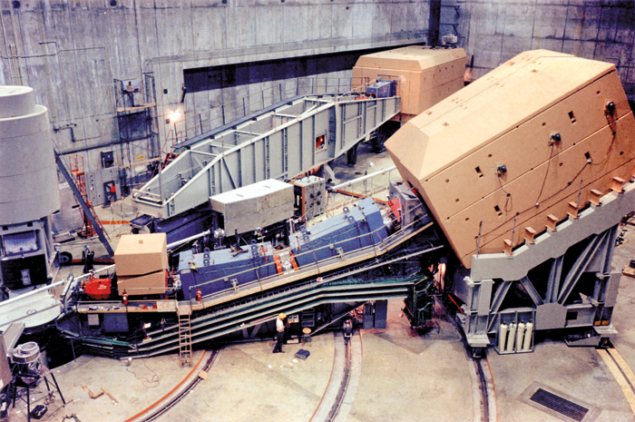

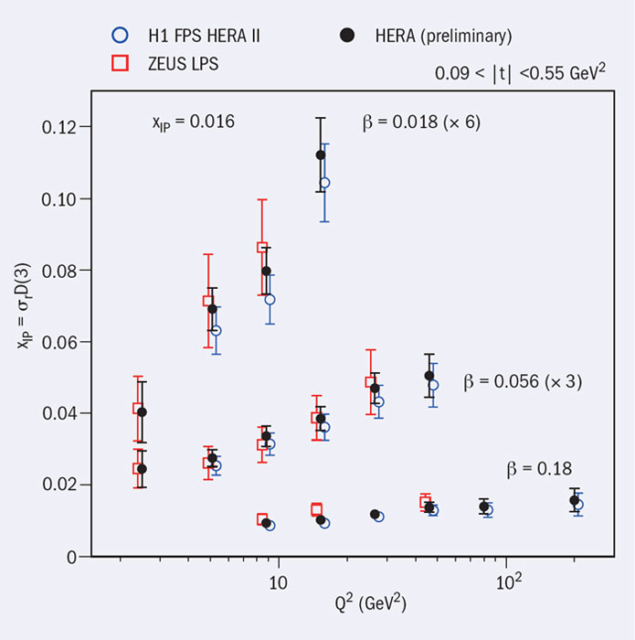

Measurements of cross-sections of diffractive processes in DIS open the opportunity to probe the parton content in the colourless nucleon, the goal being to determine diffractive PDFs of the nucleon. The H1 and ZEUS collaborations selected diffractive processes in DIS either by requiring the detection of a scattered proton in dedicated proton spectrometers (ZEUS-LPS or H1-FPS) at small angles to the direction of the proton beam, or without proton detection but instead requiring a large rapidity gap between the production of a jet or vector-meson and the proton beam direction. Figure 2 shows reduced cross-sections obtained from LPS and FPS data (and also combined), which were presented at the workshop. The LHC experiments have also started to contribute to diffraction studies. The ATLAS collaboration reported on an analysis of diffractive events selected by a rapidity gap.

Image credit: HERA Diffraction Working Group.

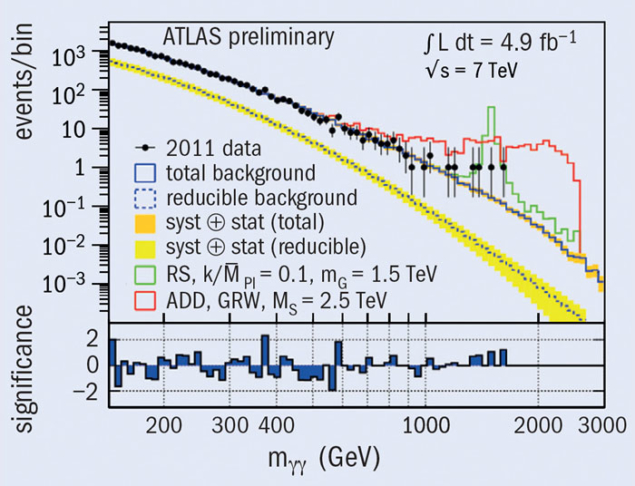

Searches and tests

At the time of the conference, the LHC experiments had only tantalizing hints of an excess in the mass region around 125 GeV using the data from 2011. It was nevertheless impressive that many results could be shown using the full 5 fb–1 of data that had been collected that year. The Higgs searches were the only ones to show any real sign of new particles. All others saw no significant indications and could only set upper limits. Experiments at both the LHC and the Tevatron have now measured WW, ZZ and WZ production with cross-sections that are consistent with Standard Model expectations, calculated to NLO and higher.

As Feltesse reminded participants in his talk, measurements of hadronic final states in DIS were the cradle for the development of the theory of strong interactions, QCD. Such measurements remain key for testing QCD predictions. New results were presented from HERA and the LHC, in which the QCD analyses have reached an impressive level of precision. While leading-order-plus-parton-shower Monte Carlos provide a good description of the data in general, a number of areas can be identified where the description is not good enough. Higher-order generators are needed here and it is important that appropriate tunes are used.

In general, NLO QCD predictions give a good description of the data. However, the uncertainty in the theory because of missing higher-order calculations is almost everywhere much larger than the experimental errors. Moreover, it was shown that in several cases the fragmentation process of partons into hadrons is not well described by NLO QCD calculations.

A central issue is the value and precision of the strong coupling constant, αS, and its running as a function of the energy scale. Many results were presented that improve the precision and show that the energy dependence is well described by QCD calculations.

There has been a great deal of progress in calculations of heavy-quark production

There has been a great deal of progress in calculations of heavy-quark production. A particular highlight is the first complete NNLO QCD prediction for the pair-production of top quarks in the quark–antiquark annihilation channel. There is also a wealth of data from HERA, the LHC, the Tevatron and the Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collider (RHIC) on the production both of quarkonia and of open charm and beauty. The precision with which the Tevatron experiments can measure the masses of both the top quark and the W boson is particularly impressive. Although the LHC experiments have more events of both sorts by now, it will still take some time before the systematic uncertainties are understood well enough to achieve similar levels of precision.

The X,Y,Z states discovered in recent years have been studied by the experiments at B factories, the LHC and the Tevatron. Their theoretical interpretations are still a challenge. The LHCb experiment has performed the world’s best measurements of the properties of the Bc meson and b baryons and has made important contributions in other areas where its ability to measure particles in the forward direction is important.

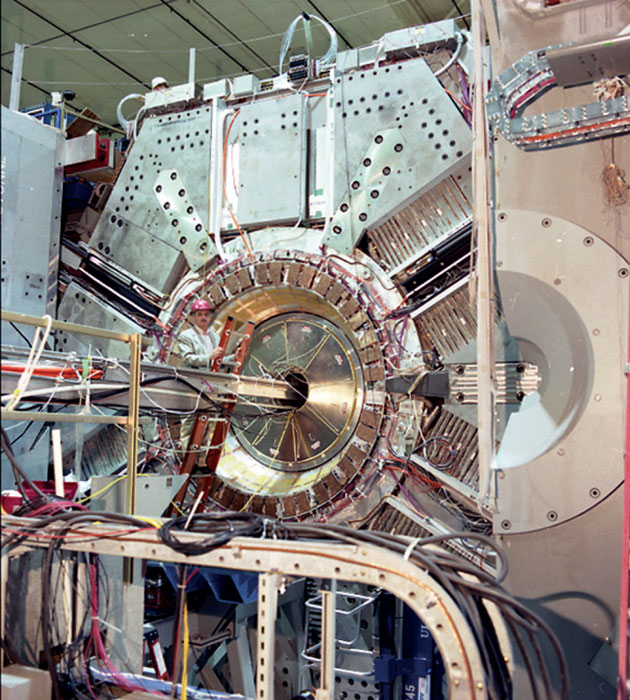

Experiments that use polarized beams in DIS on polarized targets are relevant for studying the spin structure of nucleons. New results were presented from HERMES at HERA and COMPASS at CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron, as well as from experiments at RHIC and Jefferson Lab. A tremendous amount of data has been collected and is now being analysed. Current results confirm that neither the quarks nor the gluons carry much of the nucleon spin. This leaves angular momentum. However, a picture describing the nucleon as a spatial object carrying angular momentum has yet to be settled.

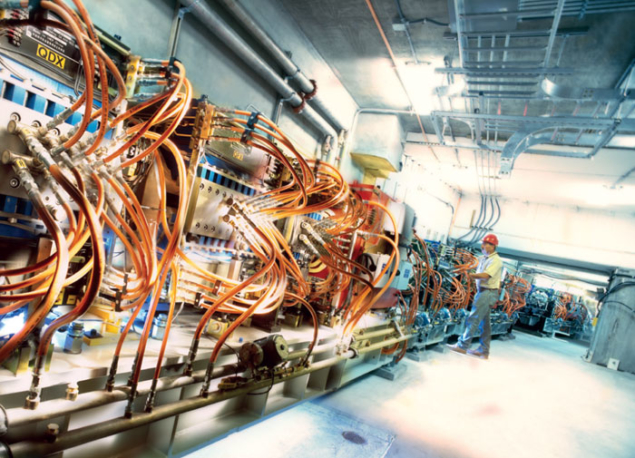

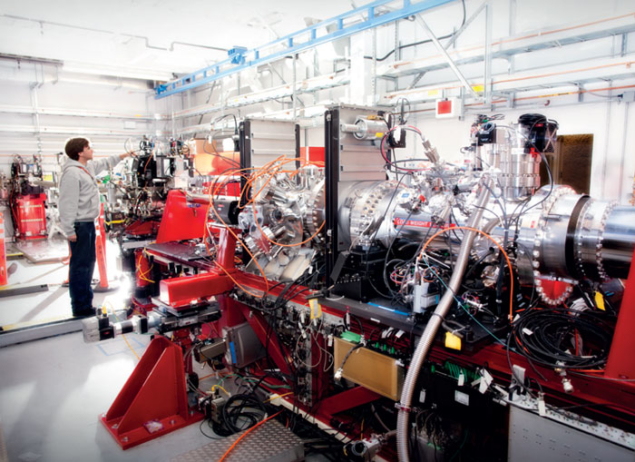

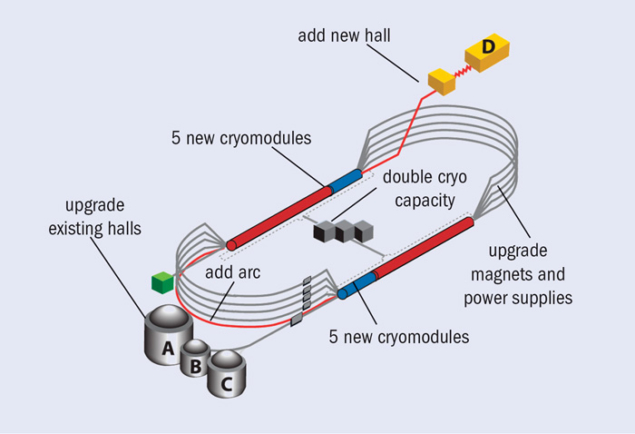

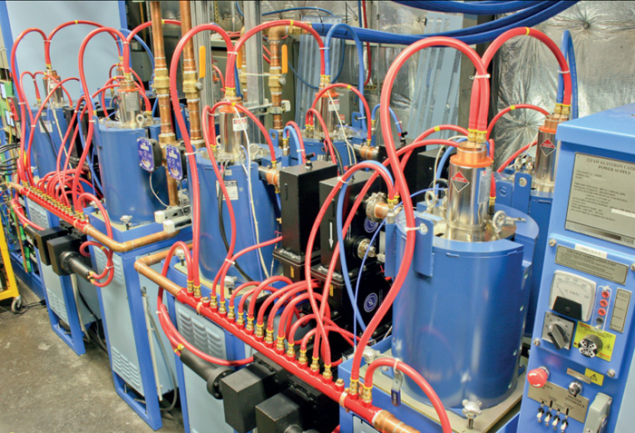

The conceptual design report for a future electron–proton collider using the LHC together with a new electron accelerator, known as the LHeC, was released a couple of months after DIS 2012. This was the main topic of the last plenary talk at the workshop. In the parallel sessions, a broad spectrum of options for the future was discussed, covering the upgrades of the LHC machine and detectors, the upgrade plans at Jefferson Lab and RHIC, as well as proposed new accelerators such as an electron–ion collider, the EIC. One of the central aims is to understand better the 3D structure of the proton in terms of generalized parton distribution functions.

DIS 2012 participants once again profited from lively and intense discussions. The conveners of the working groups worked hard to put together informative and interesting parallel sessions. They also organized combined sessions for topics that were relevant for more than one working group. For relaxation, the workshop held the conference dinner in the mediaeval castle “Burg Satzvey”, which was a big success. Many of the participants also went on one of several excursions on offer. Next year, DIS moves south and will take place on 22–26 April in Marseilles.