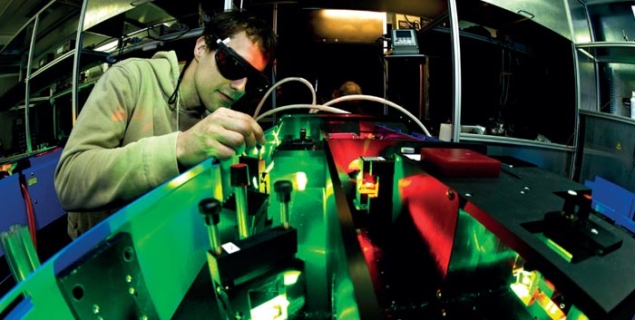

Image: Berkeley Lab.

The US LHC Accelerator Program (LARP) has successfully tested a powerful superconducting quadrupole magnet that will play a key role in developing a new beam-focusing system for the LHC. This advanced system – with other major upgrades to be implemented over the next decade – will allow the LHC to deliver a luminosity up to 10 times higher than in the original design.

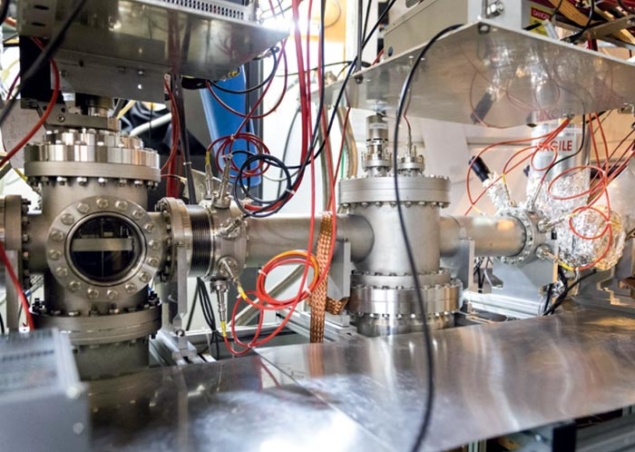

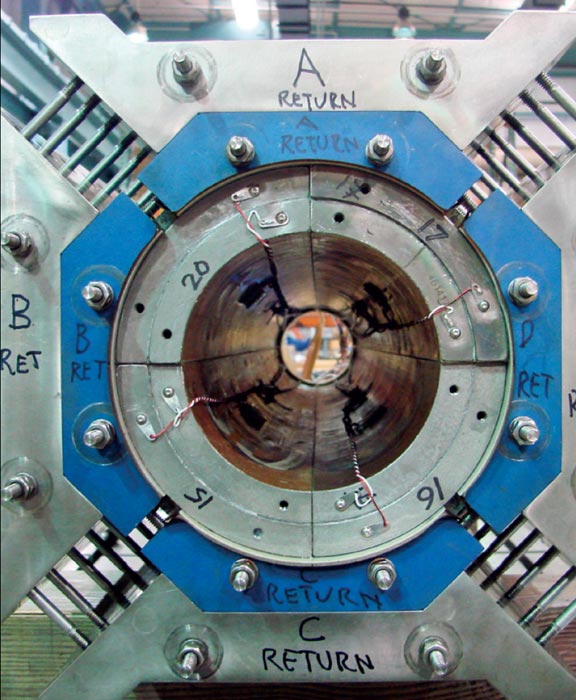

Dubbed HQ02a, the latest in LARP’s series of high-field quadrupole magnets is wound with cables of the brittle but high-performance niobium-tin superconductor (Nb3Sn). Like all LHC magnets, HQ02a is designed to operate in superfluid helium at temperatures that are close to absolute zero. However, it has a larger beam aperture than the current focusing magnets – 120 mm in diameter compared to 70 mm – and the magnetic field in the superconducting coils reaches 12 T – 50% higher than the current 8 T. The corresponding field gradient – the rate of increase of field strength over the aperture – is 170 T/m. In a recent test at Fermilab, HQ02a achieved all of its challenging objectives.

One of LARP’s primary goals is to support CERN’s plan to replace the quadrupole magnets in the interaction regions in about 10 years from now as part of the High Luminosity LHC project. Not only must the magnets produce a stronger field, they will also require a larger temperature margin and have to cope with the intense radiation, which comes hand in hand with the planned increase in the rate of energetic collisions. These requirements go beyond the capabilities of the niobium-titanium currently used in the LHC and in all previous superconducting magnets for particle accelerators.

Modern niobium-tin can operate at a higher magnetic field and with a wider temperature margin than niobium-titanium. However, it is brittle and sensitive to strain – critical factors where intense electrical currents and strong magnetic fields create enormous forces as the magnets are energized. Large forces can damage the fragile conductor or cause sudden displacements of the superconducting coils, releasing energy as heat and possibly resulting in a loss of the superconducting state – that is, a quench.

To address these challenges, LARP has adopted a mechanical support structure that is based on a thick aluminum shell, pre-tensioned at room temperature using water-pressurized bladders and interference keys. This design concept – developed at Berkeley under the US Department of Energy’s General Accelerator Development programme – was compared with the traditional collar-based clamping system used in Fermilab’s Tevatron and all of the subsequent high-energy accelerators and scaled up to 4 m in length in the LARP long “racetrack” and long quadrupoles. The HQ models further refined this mechanical design approach, in particular by incorporating full coil alignment.

The success of these tests not only establishes high-performance niobium tin as a powerful superconductor for use in accelerator magnets, it also marks a shift from R&D to development of the LARP magnets that will be installed for the LHC luminosity upgrade.

• LARP is a collaboration involving Berkeley, Brookhaven, Fermilab and SLAC, working in close partnership with CERN. It is now led by Giorgio Apollinari.