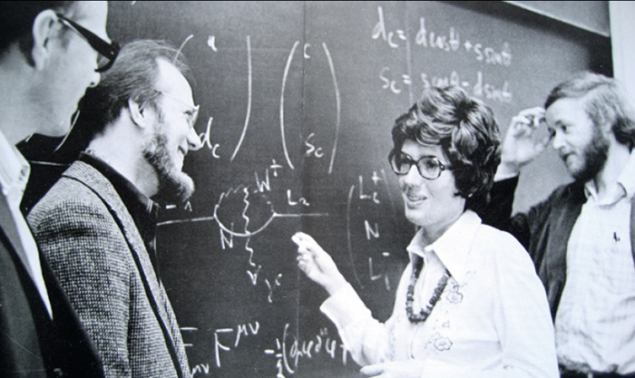

One of my most memorable experiences of CERN is from an early morning in the summer of 1966. I drove to CERN with my two small children, one and three years of age, to fetch their dad who had been on a night shift – there were no guards at the entrance in those days. I found him outside the experimental hall being interviewed by a friendly looking gentleman, who after greeting us continued asking questions and taking notes. The gentleman, as I found out afterwards, was the director-general of CERN, Bernard Gregory. This was for me an inspiring and instructive experience. Since then, CERN has grown a great deal, and attracts so many more people that the probability of a young visiting PhD student being interviewed alone by the director-general must not be so large. For me, there are other exciting new features of CERN these days, such as encountering crowds of enthusiastic young people from across the world.

The young CERN has now turned 60, its official foundation being on 29 September 1954. Its creation was a unique act, based on an unprecedented common effort by a number of distinguished scientists from several countries, not only from Europe but also from the US, among them Robert Oppenheimer and Isidor Rabi. We are all impressed by their dedication and commitment, and are grateful to them for the creation of this organization for basic research in science for peace. Since its creation, CERN has served as a “standard model” for several other international scientific organizations.

However, while CERN has just celebrated its 60th anniversary, there is one part of it that is a little older. The CERN “Group of Theoretical Studies” was created through a resolution passed by the CERN Interim Council in Amsterdam in May 1952. It was possible to form this group very quickly and for it to start work, in Copenhagen, even before the decision had been made as to where CERN would be located. Copenhagen had already been a world centre for theoretical physics for several decades. It was clear that CERN Theory would thrive there, owing to the presence of the great and incredibly influential theoretical physicist Niels Bohr, and his competent local staff. Victor Weisskopf, who was director-general of CERN in the years 1960–1964, knew Bohr well, and used to refer to him as the greatest founder of CERN. CERN Theory in Copenhagen was a lively place, and attracted many distinguished international scientists.

The CERN Annual Report for 1955 informs us that: “The Theoretical Study Division is located in the Theoretical Physics Institute, University of Copenhagen. The work of the Division has proceeded according to the programme fixed during the interim period and includes: a) scientific research on fundamental problems of nuclear physics, including theoretical problems related to the focusing of ion beams in high energy accelerators; b) training of young theoretical physicists; c) development of active co-operation with the laboratories of Liverpool and Uppsala, whose machines and equipment have been placed at the disposal of CERN.” This was what CERN’s “founding fathers” had in mind that the theorists should be doing. But, of course, except for b, that was not what the theorists actually did.

Theory went on to flourish at CERN, and the subsequent history of the Theory Division deserves a book of its own

The 1955 CERN Annual Report also informs us that the Theoretical Study Division in Copenhagen had two full-time senior staff members: Gunnar Källén and Ben R Mottelson (who was to receive the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physics). Note that these “leaders”, both born in 1926, were at the time below the age of 30. This was a general feature of the young CERN – even the accelerators were built by people who many of us would now consider as “youngsters”.

CERN Theory was expected to move gradually to Geneva. However, this took in total about five years, until 1 October 1957, when the Theory Group in Copenhagen was officially closed. The theorists who came to Geneva had their offices first at the University of Geneva, then in barracks at Geneva Airport, until they moved to the current CERN site in Meyrin. Theory went on to flourish at CERN, and the subsequent history of the Theory Division deserves a book of its own.

In 1971, I became the first female fellow of the CERN Theory Division, in 1982 the first female member of CERN’s Scientific Policy Committee, and in 1988 this committee’s first female “old boy”. Later, in the years 1998–2004, I was the adviser on member states to CERN’s director-general. I have enjoyed CERN’s international atmosphere enormously, which has given me ample opportunity to meet and talk with inspiring physicists from across the world. I also feel fortunate to have lived in a period when the amount of information revealed about the nature of the elementary constituents of matter and their interactions has been mind-boggling. CERN has been an important contributor in this respect. Who could have imagined that we would arrive at the Standard Model so “soon” – a highly successful theory of weak, electromagnetic and strong interactions?

In 2004, during the mandate of Robert Aymar as director-general, the CERN Theory Division turned into the Theory Unit, under the CERN Physics Department. Does this imply that CERN wishes to guide the theorists to work on the “focusing of ion beams”, and machines as well as equipment, as envisaged by the founding fathers in 1952? Fortunately, during my visits to CERN since, I have seen no such trend. Long live theory at CERN.