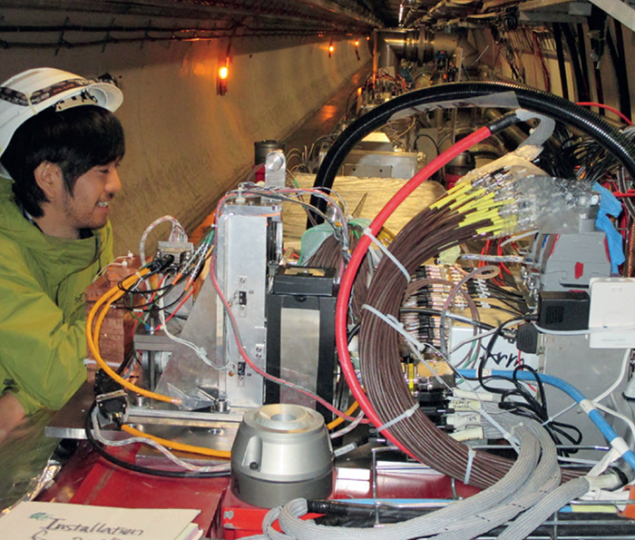

Credit: CERN

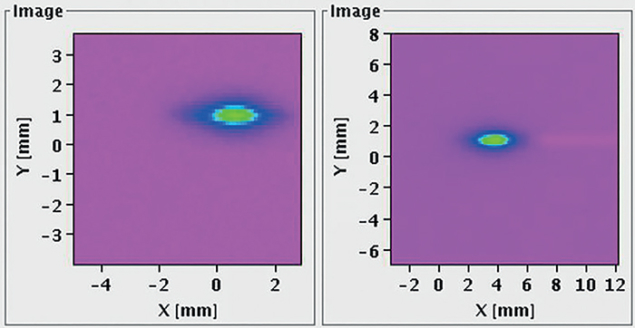

With the end of the long shutdown in sight, teams at CERN have continued preparations for the restart of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) this spring after reaching several important milestones by the end of 2014. Beams came knocking at the LHC’s door for the first time on 22–23 November, when protons from the Super Proton Synchrotron passed into the two LHC injection lines and were stopped by beam dumps just short of entering the accelerator. The LHC operations team used these tests to check the control systems, beam instrumentation and transfer-line alignment. Secondary particles – primarily muons – generated during the dump were in turn used to calibrate the two LHC experiments located close to the transfer lines: ALICE and LHCb.

During the same weekend, the operations team also carried out direct tests of LHC equipment. They looked at the timing synchronization between the beam and the LHC injection and extraction systems by pulsing the injection kicker magnets and triggering the beam-dump system in point 6, despite having no beam.

Tests of each of the eight LHC sectors continued apace. By the end of November, copper-stabilizer continuity measurements were underway in sector 4-5 and were about to start in sector 3-4. Electrical quality assurance tests were being carried out in sectors 2-3 and 7-8, and powering tests were progressing in sectors 8-1, 1-2, 5-6 and 6-7. Cooling and ventilation teams were also busy carrying out maintenance of the systems at points around the LHC ring.

Meanwhile, the operations team were training the magnets in sector 6-7. The first training quench was performed on 31 October, reaching a current of around 10,000 A, which corresponds to a magnetic field of 6.9 T and a proton beam energy of 5.8 TeV (during Run 1, the LHC ran with proton energies of up to 4 TeV). On 9 December, the team successfully commissioned sector 6-7 to the nominal energy for Run 2 – 6.5 TeV, for proton collisions at 13 TeV. The 154 superconducting dipole magnets that make up this sector were powered to around 11,000 A. This increase in nominal energy was possible thanks to the long shutdown, which began in February 2013 and allowed the consolidation of 1700 magnet interconnections, including more than 10,000 superconducting splices. The magnets in all of the other sectors are undergoing similar training prior to 6.5 TeV operation.

In mid-December, the cryogenics team finished filling the arc sections of the LHC with liquid helium. This marked an important step on the road to cooling the entire accelerator to 1.9 K. During the end-of-year break, the cryogenic system was then set to stand-by, with elements such as stand-alone magnets emptied of liquid helium. These elements were to return to cryogenic conditions in January, to allow the operations team to perform more tests on the road to the LHC’s Run 2.

The four large experiments of the LHC – ALICE, ATLAS, CMS and LHCb – are also undergoing major preparatory work for Run 2, after the long shutdown during which important programmes for maintenance and improvements were achieved. They are now entering their final commissioning phase. Here, members of the ATLAS collaboration are cleaning up the inside of the ATLAS detector prior to closing the cavern in preparation for Run 2.