By Chris Quigg

Princeton University Press

Hardback: £52.00 $75.00

Also available as an e-book, and at the CERN bookshop

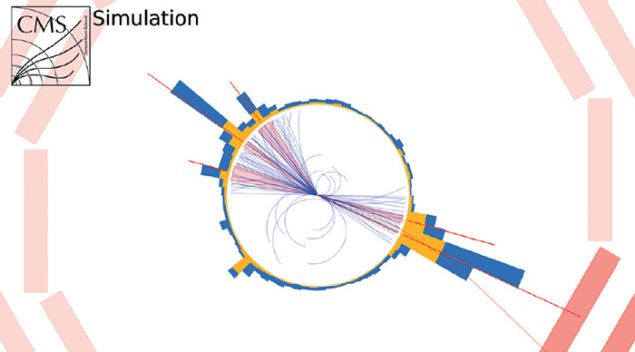

The answer lies in the second edition of Chris Quigg’s Gauge Theories of the Strong, Weak, and Electromagnetic Interactions. By a remarkable coincidence, this essentially revised volume fills in much of what the “gifted amateur” wants to know about how QFT is applied in traditional particle physics. It is hard to find words to describe Quigg’s clean, high-quality work; as an author he is a virtuoso performer. He takes the reader through the Standard Model of particle physics to the first steps beyond it, showing the most important insights, describing open questions and proposing original literature and further reading. He has designed or collected many insightful figures that illustrate beautifully the intriguing properties of the Standard Model.

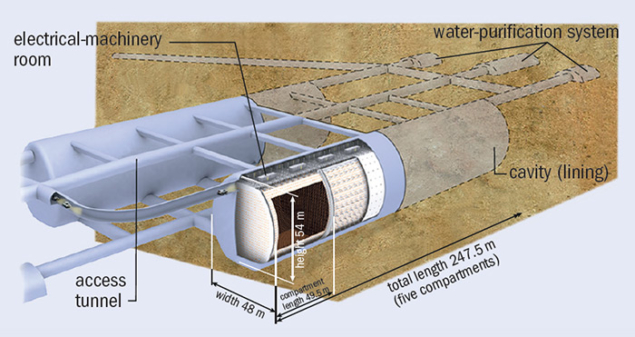

However, it’s hard for me personally to end the review on this high note since the research in the field of gauge theories of strong interactions does not end with the perturbative processes. Over the past 30 years, a vast new area has opened up with many fundamental insights. These connect to the QCD vacuum structure, the Hagedorn temperature and colour deconfinement as encapsulated in the new buzzword – quark–gluon plasma, the strongly-interacting colour-charged many-body state of quarks and gluons. Moreover, there is a wealth of numerical lattice results that accompany these developments.

I find no key word for this in the index of Quigg’s book, although there is mention of “confinement” (p336ff). On page 340, a phrase-long summary mentions the temperature of a chiral-symmetry-restoring transition (from what to what is not stated) that characterizes the lattice QCD results seen in figure 8.47 on p342. This one-phrase entry is all that describes in my estimate 20% of the experimental work at CERN of the past 25 years, and the majority of particle physics at Brookhaven for the past 15 years. In this section I also read how vacuum dielectric properties relate to confinement. I know this argument from Kenneth Wilson, as refined and elaborated on by TD Lee, and the lattice-QCD work initiated by Michael Creutz at Brookhaven, yet Quigg attributes this to an Abelian-interaction model that I did not think functioned.

The author, renowned for his work addressing two-particle interactions, represents in his book the traditional particle-physics programme as continued today at Fermilab, where the novel area of QCD many-body physics is not on the research menu, though it has come of age at CERN and Brookhaven. One can argue that this new science is not “particle physics” – but it is definitively part of “gauge theories of strong interactions”, words embedded in the title of Quigg’s book. Thus, quark–gluon plasma, vacuum structure and confinement glare brightly by their absence in this volume.

Looking again at both books it is remarkable how complementary they are for a CERN Courier reader. These are two excellent texts and together they cover most of modern QFT and its application in particle physics in 1000 pages at an affordable cost. I strongly recommend both, individually or as a set. As noted, however, the reader who purchases these two volumes may need a third one covering the new physics of deconfinement, QCD vacuum and thermal quarks and gluons – the quark–gluon plasma.