The first LHC run was highlighted by the discovery of the long-awaited Higgs boson at a mass of about 125 GeV, but we have no clue why nature chose this mass. Supersymmetry explains this by postulating a partner particle to each of the Standard Model (SM) fermions and bosons, but these new particles have not yet been found. A complementary approach to address this issue is to widen the net and look for signatures beyond those expected from the SM.

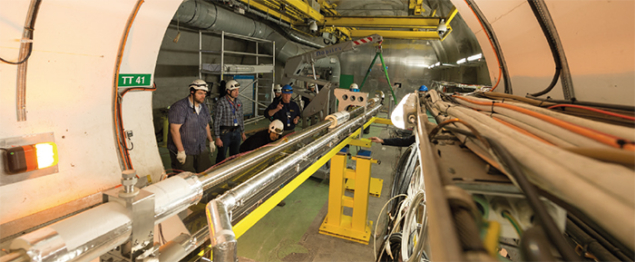

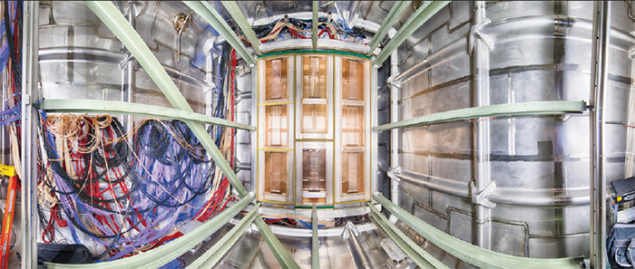

Image credit: ATLAS Collaboration.

Searches for new physics in Run 1 found no signals, and from these negative results we know that new particles may be heavy. For this reason, their decay products, such as top quarks, electroweak gauge bosons (W, Z) or Higgs bosons, may be very energetic and could be highly boosted. When such particles are produced with large momentum and decay into quark final states, the decay products often collimate into a small region of the detector. The collimated sprays of hadrons (jets) originating from the nearby quarks are therefore not reliably distinguished. Special techniques have been developed to reconstruct such boosted particles into jets with a wide opening angle, and to identify the cores associated with the quarks using soft-particle-removal procedures (grooming). ATLAS performed an extensive optimisation of top, W, Z and Higgs boson identification, exploiting a wide range of jet clustering and grooming algorithms as well as kinematic properties of jet substructure before the second LHC run. This led to a factor of two improvement in W/Z tagging, compared with the technique used previously in terms of background rejection for the same efficiency for W/Z boson transverse momenta around 300–500 GeV.

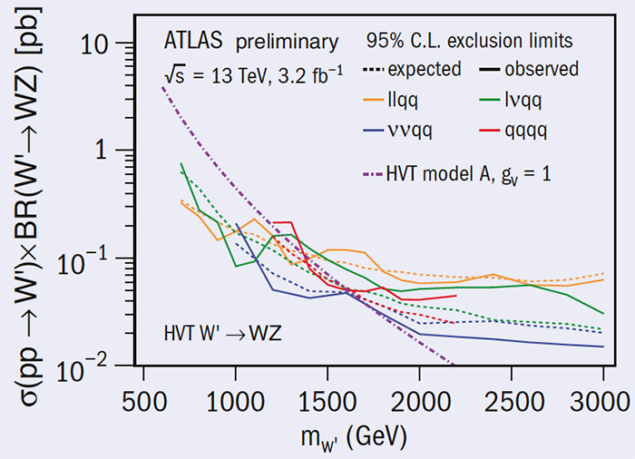

ATLAS exploited the optimised boson tagging in the search for heavy resonances decaying into a pair of two electroweak gauge bosons (WW, WZ, ZZ) or of a gauge boson and a Higgs boson (WH, ZH) at 13 TeV collisions. Events are categorised into different numbers of charged/neutral leptons, and all possible combinations are considered except for fully leptonic and fully hadronic WH or ZH decays. For the Higgs boson, only the dominant decay into b quarks is considered. Figure 1 shows the results of WZ searches with a 2015 data set corresponding to 3.2 fb–1, presented as the lower limits on the production cross-section times the branching fraction for a new massive gauge boson with certain mass. No evidence for new physics has been found with these preliminary searches.

The boosted techniques have evolved into a fundamental tool for beyond SM searches at high energy. ATLAS foresees that the search will be greatly enhanced by the techniques, and seeks opportunities to adapt them in uncharted territory for the upcoming LHC run.