Résumé

Protonthérapie : l’ère de la précision

La protonthérapie est une technique de radiothérapie innovante, qui peut traiter des tumeurs avec beaucoup plus de précision que les rayons X ou les rayons gamma. Le nombre de centres de traitement par protonthérapie augmente rapidement, et offre aux patients des traitements plus efficaces avec un risque de complications moindre. Au Centre Antoine Lacassagne, à Nice, une nouvelle installation de protonthérapie de haute énergie, qui tire son origine d’une collaboration avec le CERN vieille de 30 ans, se prépare à présent à traiter son premier patient. À performance égale, son accélérateur est quatre fois plus léger et consomme huit fois moins d’énergie que les machines actuelles, et il peut traiter tous types de tumeurs situées profondément à l’intérieur du corps humain.

Each year, millions of people worldwide undergo treatment for cancer based on focused beams of high-energy photons. Produced by electron linear accelerators (linacs), photons with energies in the MeV range are targeted on cancerous tissue where they indirectly ionise DNA atoms and therefore reduce the ability of cells to reproduce. Photon therapy has been in clinical use for more than a century, following the discovery of X-rays by Roentgen in 1896, and has helped to save or improve the quality of countless lives.

Proton therapy, which is a subclass of particle or hadron therapy, is an innovative alternative technique in radiotherapy. It can treat tumours in a much more precise manner than X- or gamma-rays because the radiation dose of protons is ballistic: protons have a definite range characterised by the Bragg peak, which depends on their energy. This initial ballistic advantage gives protons their advantage over X-rays to provide a dose deposition that better matches tumour contours while limiting the dose in the vicinity. This property, which was first identified by accelerator-pioneer Robert Wilson in 1946 when he was involved in the design of the Harvard Cyclotron Laboratory, results in a greater treatment efficiency and a lower risk of complications.

The pioneers of proton therapy used accelerators from physics laboratories at locations including Uppsala in Sweden in 1957; Boston Harvard Cyclotron Laboratory in the US in 1961; and the Swiss Institute for Nuclear Research in Switzerland in 1984. The first dedicated clinical proton-therapy facility, which was driven by a low-energy cyclotron, was inaugurated in 1989 at the Clatterbridge Centre for Oncology in the UK. The following year, a dedicated synchrotron designed at Fermilab began operating in the US at the Loma Linda University Medical Center in California. By the early 2000s, the number of treatment centres had risen to around 20, and today proton therapy is booming: some 45 facilities are in operation worldwide, with around 20 under construction and a further 30 at the planning stage in various countries around the world (see www.ptcog.ch).

Towards MEDICYC

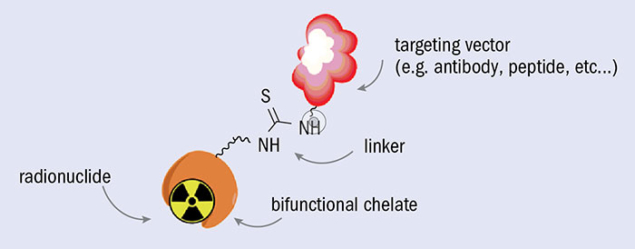

Modern proton therapy exploits an active technique called pencil-beam scanning, which creates a pointillist 3D tumour-volume painting by displacing the proton beam with appropriate magnets. Moreover, different irradiation ports are generally possible thanks to rotating gantries. This delivery technique is competitive with the most advanced forms of X-ray irradiation, such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), tomotherapy, cyberknife and others, because it uses a smaller number of entering ports and hence reduces the overall absorbed dose to the patient.

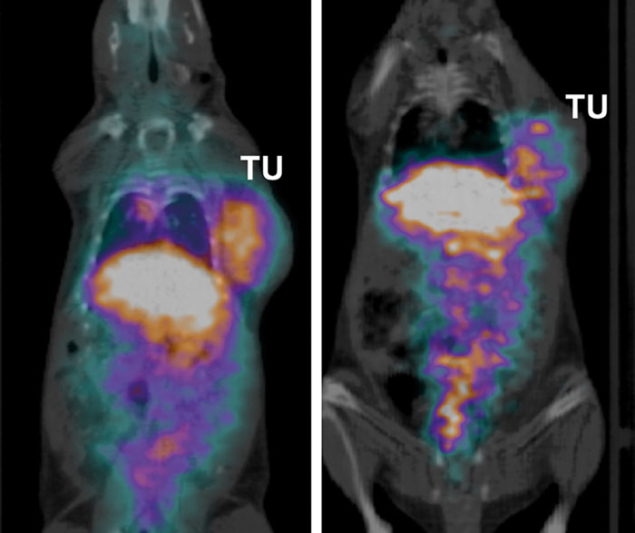

Owing to its high dose accuracy, proton therapy has historically been oriented towards the treatment of uveal melanoma and base-of-skull tumours, for which X-rays are less efficient. Today, however, proton therapy is used to treat any tumour type with a predilection for paediatric treatment. Indeed, by limiting the integral dose to an absolute minimum at the whole-body level, the side effects of radiotherapy occurring from radiation-induced cancer are reduced to a minimum.

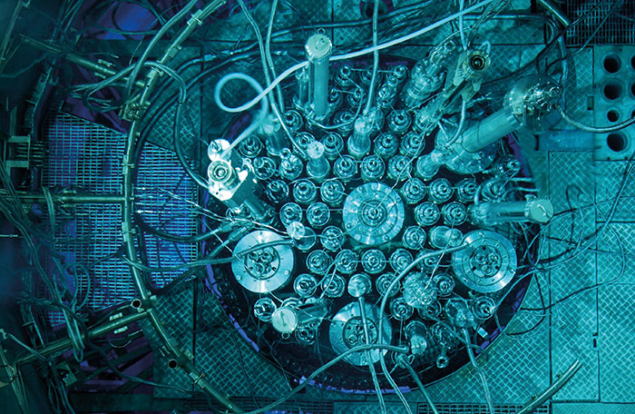

Particle physics, and CERN in particular, has played a key role in the success of proton therapy. One of the first facilities operating in Europe was MEDICYC – a 65 MeV proton medical cyclotron that was initially devoted to neutron production for cancer therapy. It was installed at the Centre Antoine Lacassagne (CAL) in Nice in 1991, where the first proton-therapy treatment for ocular melanoma was achieved in France. MEDICYC was designed by a small team of young CAL members hosted by CERN in the PS division, and the advice of the passionate experts there was key to the success of this accelerator. Preliminary studies for MEDICYC and the first test of the radiofrequency accelerating system were performed at CERN. Indeed, because the cyclotron was completed before the building that would house it, it was proposed to assemble the cyclotron magnet at CERN in the East Hall of the PS division, to perform the magnetic-measurement campaigns.

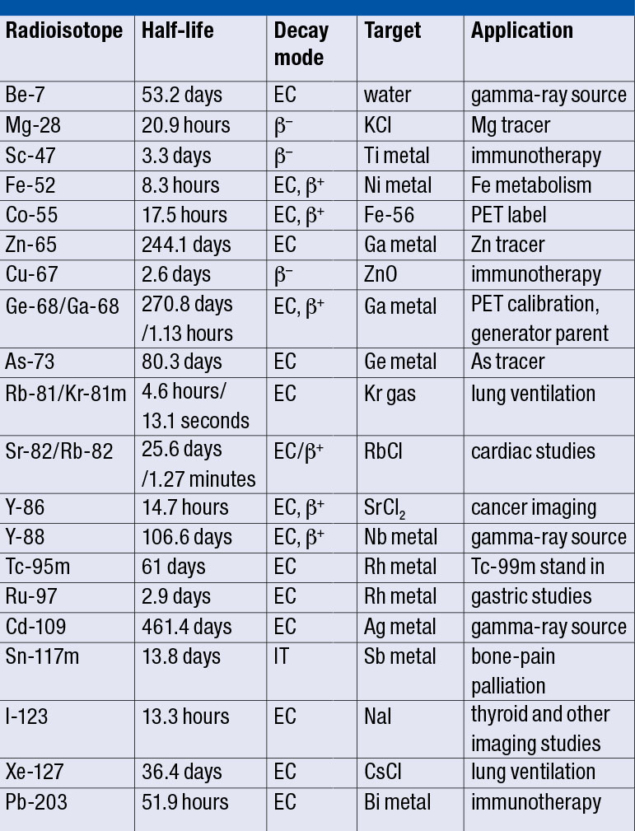

During its 25 year operational lifetime, which began in June 1991, MEDICYC has reached a high level of reliability and successfully treated more than 5500 patients for various ocular tumours with a 96% local control rate. Owing to its high-dose-profile quality (0.8 mm dose fall-off beyond the Bragg peak, which is of the utmost importance for irradiating tumours close to the optical nerve), MEDICYC will continue to run its medium-energy proton-therapy programme. Moreover, CAL is investigating a MEDICYC improvement programme for increasing the beam intensities in view of new medical-isotope production at high energies with protons and deuterons.

On 30 June this year, a new proton therapy centre called the Institut Méditerranéen de Protonthérapie (IMPT) was inaugurated at CAL, marking a new phase in European advanced hadron therapy. Joining MEDICYC as the driver of this new facility is a new cyclotron called the Superconducting Synchro-cyclotron (S2C2). This facility, which will expand the proton-therapy activity of MEDICYC, uses the latest technology to precisely target tumours while controlling the intensity and spatial distribution of the dose with fine precision. It is therefore ideal for treating base of skull, head and neck, sarcomas tumours and with priority oncopediatics tumours, and is expected to treat up to 250 patients per year in its first phase.

CERN beginnings

The new facility at CAL has its roots in a CERN-led project called EULIMA (European Light Ions Medical Accelerator) – a joint initiative at the end of the 1980s to bring the potential benefit of hadron therapy with light ions to cancer patients in Europe. Historically, CAL was involved with several European institutes to undertake feasibility studies for EULIMA. The feasibility study group was hosted by CERN and the main design option for the accelerator was a four-magnetic-sector cyclotron with a single large cylindrical superconducting excitation coil designed by CERN magnet-specialist Mario Morpurgo. CAL was selected as a candidate site to host the EULIMA prototype because it offered both adequate space in the MEDICYC building to house the machine and treatment rooms, while also offering an adequate supply of medical, scientific and technical staff in an attractive site.

When the EULIMA came to an end in 1992, the empty EULIMA hall was available for future development projects in high-energy proton therapy. Therefore, in 2011, we were able to construct the new S2C2 facility at CAL at low cost. This compact, approximately 40 tonne facility provides proton beams with an energy of 230 MeV and delivers its dose using dynamic pencil-beam scanning (PBS). Its design is the result of a collaboration between AIMA (a spin-out company from CAL) and Belgian medical firm IBA.

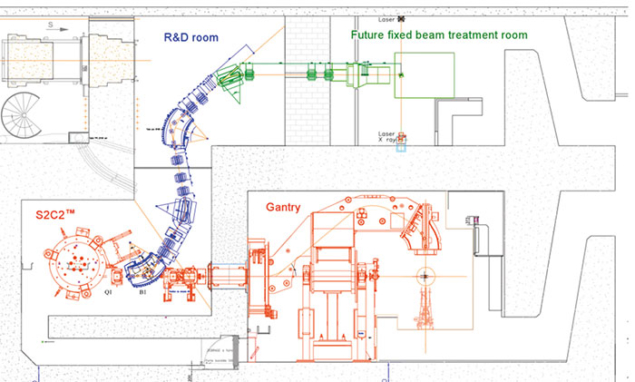

The facility comprises a beamline that feeds an R&D room for research teams, which have decided to commit themselves to a national research programme called France Hadron. The programme gathers several hadron-therapy centres based at Paris-Orsay, Lyon, Caen, Toulouse and Nice, in addition to several universities and national public research institutions, to co-ordinate and organise a national programme of research and training in hadron therapy. This programme aims at bringing nuclear-physics techniques to clinical research through dosimetry, radiation biology, imaging, control of target positioning, and quality-control instruments.

As is the case for eye treatment at MEDICYC, the new facility will operate in co-operation with the Léon Bérard cancer centre in Lyon and other oncologic centres in the south of France. The new high-energy proton facility displays many innovative technological breakthroughs compared with existing systems. The accelerator is four-times lighter and consumes eight-times less energy than current machines for the same performance, and its maximum energy of 230 MeV can treat all tumours deep in the human body up to a depth of 32 cm. Its significantly lower cost represents a particularly attractive alternative compared with the global industrial standard. It also foreshadows a major development of proton therapy in the coming years, because compact synchrocyclotron technology is also being developed for the acceleration of alpha particles and heavier ions for hadron therapy.

A major innovation is its rotating compact gantry, the first prototype of which was installed in the US in 2013. The new beamline has a mobility that allows operators to direct the radiation beam in different incidences around the patient and offer unprecedented compactness, reducing costs further. The new S2C2 and the future upgrading programme of MEDICYC embody the medical mission of CAL at large by bringing together advanced proton therapy for treating patients and scientific research activities with multidisciplinary teams of medical physicists and radiobiologists.