Protons and neutrons, the building blocks of nuclear matter, constitute about 99.9% of the mass of all visible matter in the universe. In contrast to more familiar atomic and molecular matter, nuclear matter is also inherently complex because the interactions and structures in nuclear matter are inextricably mixed up: its constituent quarks are bound by gluons that also bind themselves. Consequently, the observed properties of nucleons and nuclei, such as their mass and spin, emerge from a complex, dynamical system governed by quantum chromodynamics (QCD). The quark masses, generated via the Higgs mechanism, only account for a tiny fraction of the mass of a proton, leaving fundamental questions about the role of gluons in nucleons and nuclei unanswered.

The underlying nonlinear dynamics of the gluon’s self-interaction is key to understanding QCD and fundamental features of the strong interactions such as dynamical chiral symmetry breaking and confinement. Despite the central role of gluons, and the many successes in our understanding of QCD, the properties and dynamics of gluons remain largely unexplored.

Positive evaluation

To address these outstanding puzzles in modern nuclear physics, researchers in the US have proposed a new machine called the Electron Ion Collider (EIC). In July this year, a report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine commissioned by the US Department of Energy (DOE) positively endorsed the EIC proposal. “In summary, the committee finds a compelling scientific case for such a facility. The science questions (see “EIC’s scientific goals: in brief”) that an EIC will answer are central to completing an understanding of atoms as well as being integral to the agenda of nuclear physics today. In addition, the development of an EIC would advance accelerator science and technology in nuclear science; it would also benefit other fields of accelerator-based science and society, from medicine through materials science to elementary particle physics.”

From a broader perspective, the versatile EIC will, for the first time, be able to systematically explore and map out the dynamical system that is the ordinary QCD bound state, triggering a new area of study. Just as the advent of X-ray diffraction a century ago triggered tremendous progress in visualising and understanding the atomic and molecular structure of matter, and as the introduction of large-scale terrestrial and space-based probes in the last two to three decades led to precision observational cosmology with noteworthy findings, the EIC is foreseen to play a similarly transformative role in our understanding of the rich variety of structures at the subatomic scale.

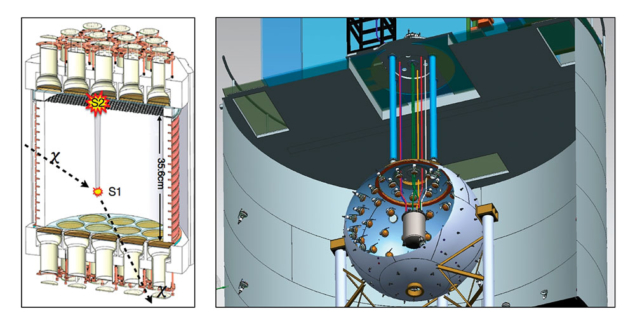

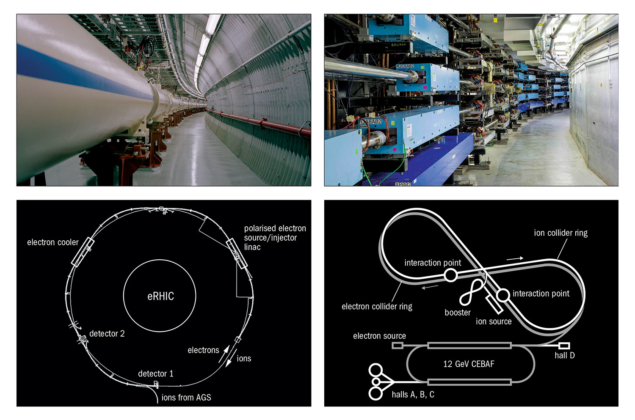

Two pre-conceptual designs for a future high-energy and high-luminosity polarised EIC have evolved in the US using existing infrastructure and facilities (figure 1). One proposes to add an electron storage ring to the existing Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collider (RHIC) complex at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) to enable electron–ion collisions. The other pre-conceptual design proposes a new electron and ion collider ring at Jefferson Laboratory (JLab), utilising the 12 GeV upgraded CEBAF facility (CERN Courier March 2018 p19) as the electron injector. The requirement that the EIC has a high luminosity (approximately 1034 cm–2 s–1) demands new ways to “cool” the hadrons, beyond the capabilities of current technology. A novel, coherent electron-cooling technique is under development at BNL, while JLab is focussing on the extension of conventional electron cooling techniques to significantly higher energy and to use bunched electron beams for the first time. The luminosity, polarisation and cooling requirements are coupled to the existence and further development of high brilliance (polarised) electron and ion sources, benefitting from the existing experience at JLab, BNL and collaborating institutions.

The EIC is foreseen to have at least two interaction regions and thus two large detectors. The physics-driven requirements on the EIC accelerator parameters, and extreme demands on the kinematic coverage for measurements, makes it particularly challenging to integrate into the interaction regions of the main detector and dedicated detectors along the beamline in order to register all particles down to the smallest angles. The detectors would be fully integrated in the accelerator over a region of about 100 m, with a secondary focus to even detect particles with angles and rigidities near the main ion beams. To quickly separate both beams into their respective beam lines while providing the space and geometry required by the physics programme, both the BNL and JLab pre-conceptual designs incorporate a large crossing angle of 20–50 mrad. This achieves a hermetic acceptance and also has the advantage of avoiding the introduction of separator dipoles in the detector vicinity that would generate huge amounts of synchrotron radiation. The detrimental effects of this crossing angle on the luminosity and beam dynamics would be compensated by a crab-crossing radio-frequency scheme, which has many synergies with the LHC high-luminosity upgrade (CERN Courier May 2018 p18).

Modern particle detector and readout systems will be at the heart of the EIC, driven by the demand for high precision on particle detection and identification of final-state particles. A multipurpose EIC detector needs excellent hadron–lepton–photon separation and characterisation, full acceptance, and to go beyond the requirements of most particle-physics detectors when it comes to identifying pions, kaons and protons. This means that different particle-identification technologies have to be integrated over a wide rapidity range in the detector to cover particle momenta from a couple of 100 MeV to several tens of GeV. To address the demands on detector requirements, an active detector R&D programme is ongoing, with key technology developments including large, low-mass high-resolution tracking detectors and compact, high-resolution calorimetry and particle identification.

The path ahead

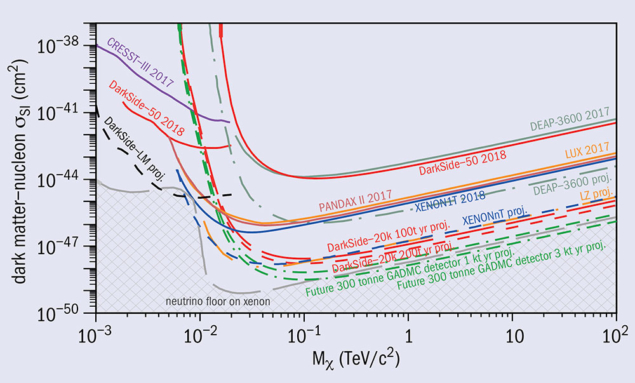

A high-energy and high-luminosity electron–ion collider capable of a versatile range of beam energies, polarisations and ion species is the only tool to precisely image the quarks and gluons, and their interactions, and to explore the new QCD frontier of strong colour fields in nuclei – to understand how matter at its most fundamental level is made. In recognition of this, in 2015 the Nuclear Science Advisory Committee (NSAC), advising the DOE, and the National Science Foundation (NSF) recommended an EIC in its long-range plan as the highest priority for new facility construction. Subsequently, a National Academy of Sciences (NAS) panel was charged to review both the scientific opportunities enabled by an EIC and the benefits to other fields of science and society, leading to the report published in July.

The NAS report strongly articulates the merit of an EIC, also citing its role in maintaining US leadership in accelerator science. This could be the basis for what is called a Critical Decision-0 or Mission Need approval for the DOE Office of Science, setting in motion the process towards formal project R&D, engineering and design, and construction. The DOE Office of Nuclear Physics is already supporting increased efforts towards the most critical generic EIC-related accelerator research and design.

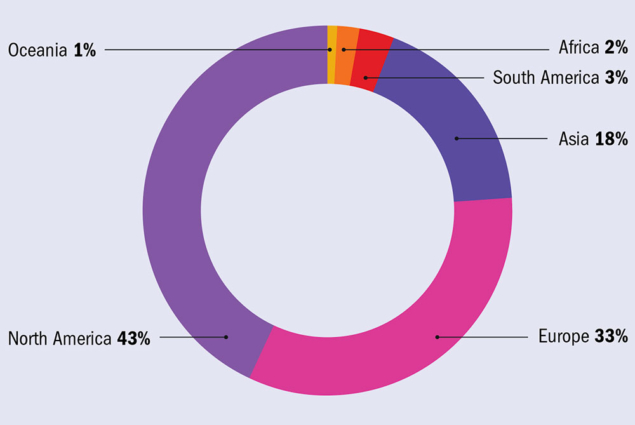

But the EIC is by no means a US-only facility (figure 2). A large international physics community, comprising more than 800 members from 150 institutions in 30 countries and six continents, is now energised and working on the scientific and technical challenges of the machine. An EIC users group (www.eicug.org) was formed in late 2015 and has held meetings at the University of California at Berkeley, Argonne National Laboratory, and Trieste, Italy, with the most recent taking place at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC in July. The EIC user group meetings in Trieste and Washington included presentations of US and international funding agency perspectives, further endorsing the strong international interest in the EIC. Such a facility would have capabilities beyond all previous electron-scattering machines in the US, Europe and Asia, and would be the most sophisticated and challenging accelerator currently proposed for construction in the US.