It is some 60 years since the conception of positron emission tomography (PET), which revolutionised the imaging of physiological and biochemical processes. Today, PET scanners are used around the world, in particular providing quantitative and 3D images for early-stage cancer detection and for maximising the effectiveness of radiation therapies. Some of the first PET images were recorded at CERN in the late 1970s, when physicists Alan Jeavons and David Townsend used the technique to image a mouse. While the principle of PET already existed, the detectors and algorithms developed at CERN made a major contribution to its development. Techniques from high-energy physics could now be about to enable another leap in PET technology.

In a typical PET scan, a patient is administered with a radioactive solution that concentrates in malignant cancers. Positrons from β+ decay annihilate with electrons from the body, resulting in the back-to-back emission of two 511 keV gamma rays that are registered in a crystal via the photoelectric effect. These signals are then used to reconstruct an image. Significant advances in PET imaging have taken place in the past few decades, and the vast majority of existing scanners use inorganic crystals – usually bismuth germanium oxide (BGO) or lutetium yttrium orthosilicate (LYSO) – organised in a ring to detect the emitted PET photons.

The main advantage of crystal detectors is their large stopping power, high probability of photoelectric conversion and good energy resolution. However, the use of inorganic crystals is expensive, limiting the number of medical facilities equipped with PET scanners. Moreover, conventional detectors are limited in their axial field of view: currently a distance of only about 20 cm along the body can be simultaneously examined from a single-bed position, meaning that several overlapping bed positions are needed to carry out a whole-body scan, and only 1% of quanta emitted from a patient’s body are collected. Extension of the scanned region from around 20 to 200 cm would not only improve the sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio, but also reduce the radiation dose needed for a whole-body scan.

To address this challenge, several different designs for whole-body scanners have been introduced based on resistive-plate chambers, straw tubes and alternative crystal scintillators. In 2009, particle physicist Paweł Moskal of Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland, introduced a system that uses inexpensive plastic scintillators instead of inorganic ones for detecting photons in PET systems. Called the Jagiellonian PET (J-PET) detector, and based on technologies already employed in the ATLAS, LHCb, KLOE, COSY-11 and other particle-physics experiments, the aim is to allow cost effective whole-body PET imaging.

Whole-body imaging

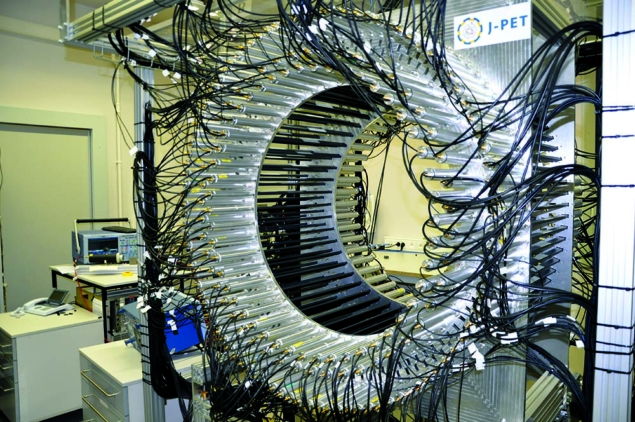

The current J-PET setup comprises a ring of 192 detection modules axially arranged in three layers as a barrel-shaped detector and the construction is based on 17 patent-protected solutions. Each module consists of a 500 × 19 × 7 mm3 scintillator strip made of a commercially available material called EJ-230, with a photomultiplier tube (PMT) connected at each side. Photons are registered via the Compton effect and each analog signal from the PMTs is sampled in the voltage domain at four thresholds by dedicated field-programmable gate arrays.

In addition to recording the location and time of the electron—positron annihilation, J-PET determines the energy deposited by annihilation photons. The 2D position of a hit is known from the scintillator position, while the third space component is calculated from the time difference of signals arriving at both ends of scintillator, enabling direct 3D image reconstruction. PMTs connected to both sides of the scintillator strips compensate for the low detection efficiency of plastic compared to crystal scintillators and enable multi-layer detection. A modular and relatively easy to transport PET scanner with a non-magnetic and low density central part can be used as a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed-tomography compatible insert. Furthermore, since plastic scintillators are produced in various shapes, the J-PET approach can be also introduced for positron emission mammography (PEM) and as a range monitor for hadron therapy.

The J-PET detector offers a powerful new tool to test fundamental symmetries

J-PET can also build images from positronium (a bound state of electron and positron) that gets trapped in intermolecular voids. In about 40% of cases, positrons injected into the human body create positronium with a certain lifetime and other environmentally sensitive properties. Currently this information is neither recorded nor used for PET imaging, but recent J-PET measurements of the positronium lifetime in normal and cancer skin cells indicate that the properties of positronium may be used as diagnostic indicators for cancer therapy. Medical doctors are excited by the avenues opened by J-PET. These include a larger axial view (e.g. to check correlations between organs separated by more than 20 cm in the axial direction), the possibility of performing combined PET-MRI imaging at the same time and place, and the possibility of simultaneous PET and positronium (morphometric) imaging paving the way for in vivo determination of cancer malignancy.

Such a large detector is not only potentially useful for medical applications. It can also be used in materials science, where PALS enables the study of voids and defects in solids, while precise measurements of positronium atoms leads to morphometric imaging and physics studies. In this latter regard, the J-PET detector offers a powerful new tool to test fundamental symmetries.

Combinations of discrete symmetries (charge conjugation C, parity P, and time reversal T) play a key role in explaining the observed matter–antimatter asymmetry in the universe (CP violation) and are the starting point for all quantum field theories preserving Lorentz invariance, unitarity and locality (CPT symmetry). Positronium is a good system enabling a search for C, T, CP and CPT violation via angular correlations of annihilation quanta, while the positronium lifetime measurement can be used to separate the ortho- and para-positronium states (o-Ps and p-Ps). Such decays also offer the potential observation of gravitational quantum states, and are used to test Lorentz and CPT symmetry in the framework of the Standard Model Extension.

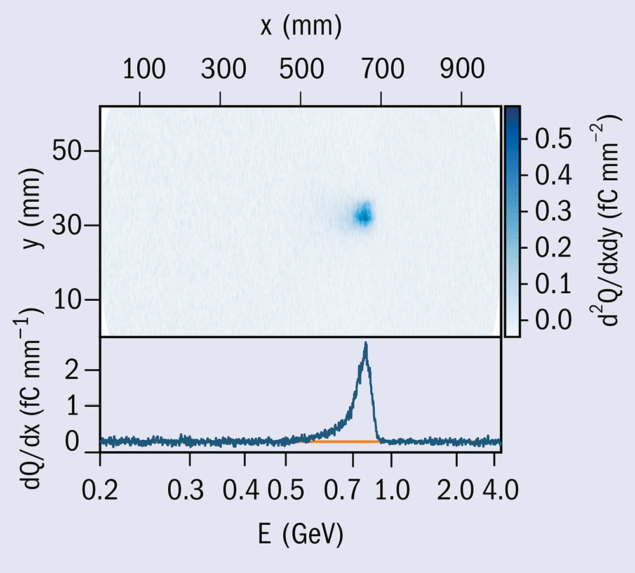

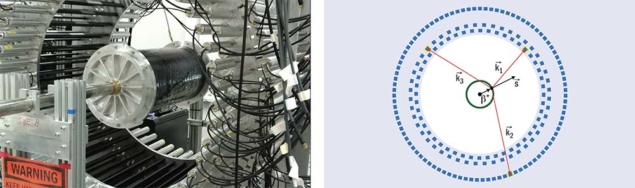

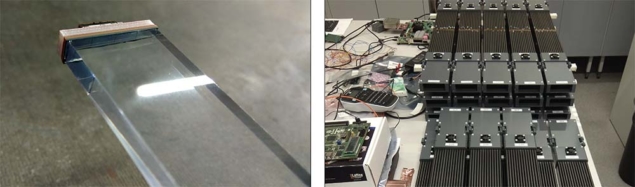

At J-PET, the following reaction chain is predominantly considered: 22Na → 22Ne∗ e+ νe, 22Ne∗ → 22Ne γ and e+e– → o-Ps → 3γ annihilation. The detection of 1274 keV prompt γ emission from 22Ne∗ de-excitation is the start signal for the positronium-lifetime measurement. Currently, tests of discrete symmetries and quantum entanglement of photons originating from the decay of positronium atoms are the main physics topics investigated by the J-PET group. The first data taking was conducted in 2016 and six data-taking campaigns have concluded with almost 1 PB of data. Physics studies are based on data collected with a point-like source placed in the centre of the detector and covered by a porous polymer to increase the probability of positronium formation. A test measurement with a source surrounded by an aluminium cylinder was also performed. The use of a cylindrical target (figure 1, left) allows researchers to separate in space the positronium formation and annihilation (cylinder wall) from the positron emission (source). Most recently, measurements by J-PET were also performed with a cylinder with the inner wall covered by the porous material.

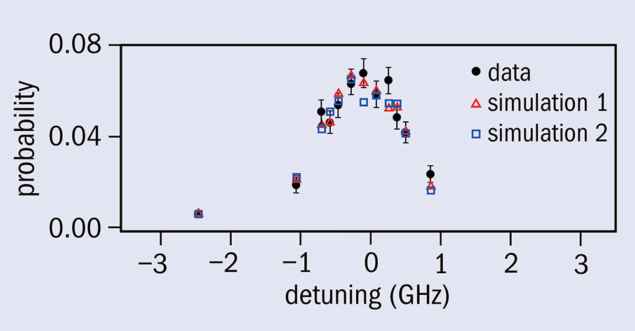

The J-PET programme aims to beat the precision of previous measurements for C, CP and CPT symmetry tests in positronium, and to be the first to observe a potential T-symmetry violation. Tests of C symmetry, on the other hand, are conducted via searches for forbidden decays of the positronium triplet state (o-Ps) to 4γ and the singlet state (p-Ps) to 3γ. Tests of the other fundamental symmetries and their combinations will be performed by the measurement of the expectation values of symmetry-odd operators constructed using spin of o-Ps, momenta and polarisation vectors of photons originating from its annihilation (figure 1, right). The physical limit of such tests is expected at the level of about 10−9 due to photo–photon interaction, which is six orders of magnitude smaller than the present experimental limits (e.g. at the University of Tokyo and by the Gammasphere experiment).

Since J-PET is built of plastic scintillators, it provides an opportunity to determine the photon’s polarisation through the registration of primary and secondary Compton scatterings in the detector. This, in turn, enables the study of multi-partite entanglement of photons originating from the decays of positronium atoms. The survival of particular entanglement properties in the mixing scenario may make it possible to extract quantum information in the form of distinct entanglement features, e.g. from metabolic processes in human bodies.

Currently a new, fourth J-PET layer is under construction (figure 2), with a single unit of the layer comprising 13 plastic-scintillator strips. With a mass of about 2 kg per single detection unit, it is easy to transport and to build on-site a portable tomographic chamber whose radius can be adjusted for different purposes by using a given number of such units.

The J-PET group is a collaboration between several Polish institutions – Jagiellonian University, the National Centre for Nuclear Research Świerk and Maria Curie-Skłodowska University – as well as the University of Vienna and the National Laboratory in Frascati. The research is funded by the Polish National Centre for Research and Development, by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education and by the Foundation for Polish Science. Although the general interest in improved quality of medical diagnosis was the first step towards this new detector for positron annihilation, today the basic-research programme is equally advanced. The only open question at J-PET is whether a high-resolution full human body tomographic image will be presented before the most precise test of one of nature’s fundamental symmetries.