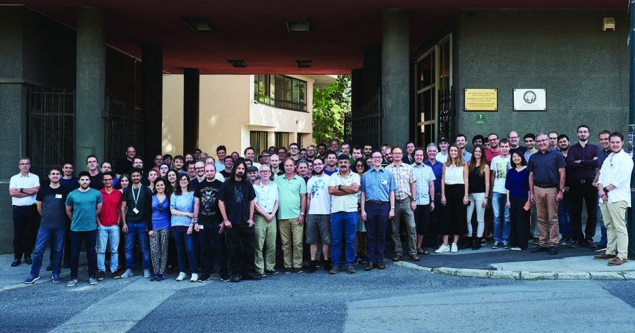

The 7th International Conference on New Frontiers in Physics (ICNFP 2018) took place on 4–12 July in Kolymbari, Crete, Greece, bringing together about 250 participants.

The opening talk was given by Slava Mukhanov and was dedicated to Stephen Hawking. To mention some of the five special sessions featured, the memorial session of Lev Lipatov, a leading figure worldwide in the high-energy behaviour of quantum field theory (see CERN Courier January/February 2018 p50), the session on quantum chromodynamics and the round table on the future of fundamental physics chaired by Albert de Roeck, saw a high number of attendees.

Alongside the main conference sessions, there were 10 workshops. Among these, the one on heavy neutral leptons highlighted novel mechanisms for producing sterile-neutrino dark matter and prospects for future searches of such dark matter with the next generation of space-based X-ray telescopes, including Spektr-RG, Hitomi and Athena+.

The workshop on instrumentation and methods in high-energy physics focused on the latest developments and the performance of complex detector systems, including triggering, data acquisition and signal-control systems, with an emphasis on large-scale facilities in nuclear physics, particle physics and astrophysics. This programme attracted many participants and led to the exchange of scientific information between different physics communities.

The workshop on new physics paradigms after the Higgs-boson and gravitational-wave discoveries provided an opportunity both to review results from searches for gravitational waves and to show plans for future precision measurements of Standard Model parameters at the LHC.

The workshop also featured several theory talks covering a wide range of subjects, including the implementation of supersymmetry breaking in string theory, new developments in early-universe cosmology and beyond-Standard Model physics. ICNFP 2018 also saw the first workshop on frontiers in gravitation, astrophysics and cosmology, which strengthened the Asian presence at ICNFP, gathering many participants from the Asia Pacific region.

For the second time in the ICNFP series, a workshop on quantum information and quantum foundations took place, with the aim of promoting discussions and collaborations between theorists and experimentalists working on these topics.

Yakir Aharonov gave a keynote lecture on novel conceptual and practical applications of so-called weak values and weak measurements, showing that they lead to many interesting hitherto-unnoticed phenomena. The latter include, for instance, a “separation” of a particle from its physical variables (such as its spin), emergent correlations between remote parties defying fundamental classical concepts, and a completely top-down hierarchical structure in quantum mechanics, which stands in contrast to the concept of reductionism. As exemplified in the talk of Avshalom Elitzur, the latter could be explained using self-cancelling pairs of positive and negative weak values.

Sandu Popescu, Pawel Horodecki, Marek Czachor and Eliahu Cohen presented many new phenomena involving quantum nonlocality in space and time, which open new avenues for extensive research. Ebrahim Karimi discussed various applications of structured quantum waves carrying orbital angular momentum (either photons or massive particles) and also discussed how to manipulate the topology of optical polarisation knots. Onur Hosten emphasised the importance of cold atoms for quantum metrology.

The workshop also featured many excellent talks discussing the intriguing relations between quantum information and condensed-matter physics or quantum optics. Some connections with quantum gravity, based on entanglement, complexity and quantum thermodynamics, were also discussed. Another topic presented was the comparison between the role of spin and polarisation in high-energy physics and quantum optics. In both of these fields, one should consider the total angular momentum, not the spin alone, and helicity is a very helpful concept in both, too.

Future accelerator facilities such as the low-energy heavy-ion accelerator centres FAIR in Darmstadt, Germany, and NICA at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia, were also discussed, particularly in the workshop on physics at FAIR-NICA-SPS-BES/RHIC accelerator facilities. Here new ideas as well as overview talks on current and future experiments on the formation and exploration of baryon-rich matter in heavy-ion collisions were presented.

The MoEDAL collaboration at CERN, which searches for highly ionising messengers of new physics such as magnetic monopoles, organised a mini-workshop on highly ionising avatars of new physics. The workshop provided a forum for experimentalists and phenomenologists to meet, discuss and expand this discovery frontier. The latest results from the ATLAS, CMS, MoEDAL and IceCube experiments were presented, and some important developments in theory and phenomenology were introduced for the first time. Highlights of the workshop included monopole production via photon fusion at colliders, searches for heavy neutral leptons and other long-lived particles at the LHC, regularised Kalb–Ramond monopoles with finite energy, and monopole detection techniques using solid-state and Timepix detectors.

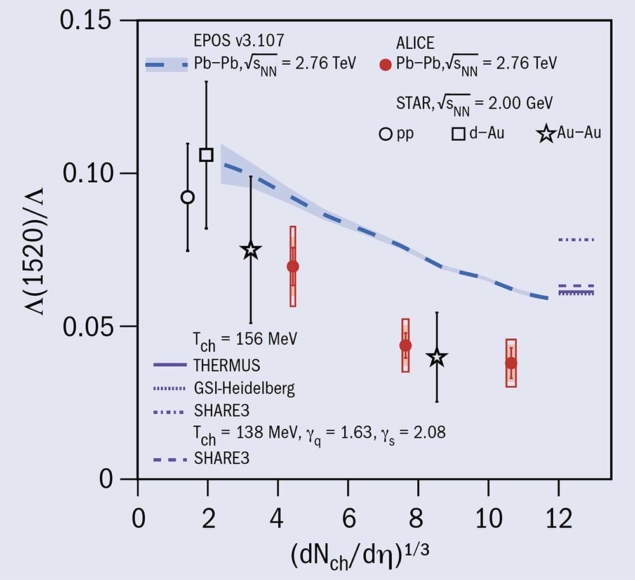

Finally, on the education and outreach front, Despina Hatzifotiadou gave LHC “masterclasses” in collaboration with EKFE (the laboratory centre for physical sciences) to 30 high-school students and teachers, who had the opportunity to analyse data from the ALICE experiment and “observe” strangeness enhancement in relativistic heavy-ion collisions.

The next ICNFP conference will take place on 21–30 August 2019 in Kolymbari, Crete, Greece.