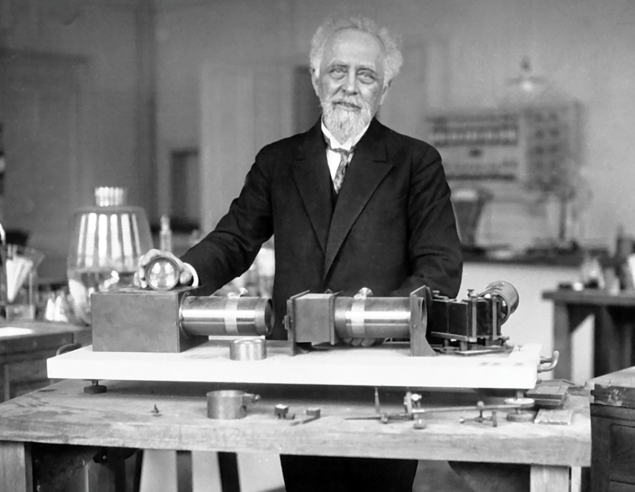

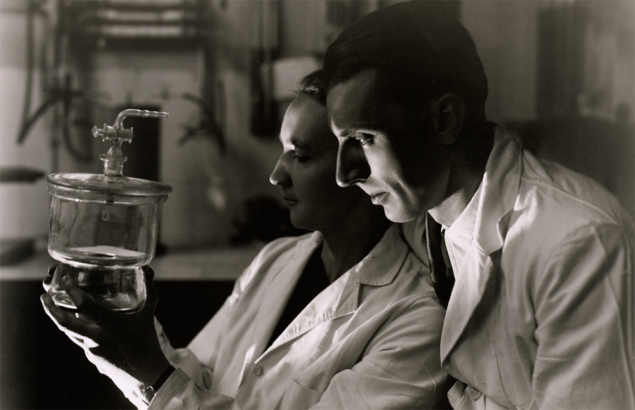

Se souvient-on des images du laboratoire de Pierre et Marie Curie ? «Ce n’est qu’une baraque en planches, au sol bitumé et au toit vitré, protégeant incomplètement contre la pluie, dépourvue de tout aménagement », selon Marie Curie. Même ses collègues étrangers se désolent alors du peu de moyens dont ils disposent. Le chimiste allemand Wilhelm Ostwald déclare : « Ce laboratoire tenait à la fois de l’étable et du hangar à pommes de terre. Si je n’y avais pas vu des appareils de chimie, j’aurais cru que l’on se moquait de moi ». Dans les années 1920, des journaux témoignent de la misère des laboratoires. « Il y en a dans les greniers, d’autres dans des caves, d’autres en plein air… », rapporte le Petit Journal en 1921. Augmenter les moyens de la recherche pour se mettre au niveau de pays comme l’Allemagne devient une cause nationale.

Entre les deux guerres, Jean Perrin, prix Nobel de physique 1926 pour ses travaux sur l’existence des atomes, s’engage pour le développement de la science, avec le soutien de nombreux scientifiques. Grâce à des financements de la Fondation Rothschild, il crée l’Institut de biologie physico-chimique, où travaillent pour la première fois des chercheurs à temps plein. En 1935, il obtient la création de la Caisse nationale de la recherche scientifique qui finance des projets universitaires et des bourses de chercheurs. L’un de ses premiers boursiers en 1937 est le jeune Lew Kowarski, issu du laboratoire de Frédéric Joliot-Curie au Collège de France. En mai 1939, ils déposent avec Hans von Halban, via la Caisse, les brevets qui esquissent la production d’énergie nucléaire et le principe de la bombe atomique.

Avec l’arrivée du gouvernement de Léon Blum en 1936, un sous-secrétaire d’État à la recherche est nommé pour la première fois. Autre première : trois femmes intègrent le gouvernement à une époque où elles n’avaient pas encore le droit de vote en France. Irène Joliot-Curie accepte ce poste pour trois mois afin de soutenir la cause féminine et celle de la recherche scientifique. Pendant cette courte période, elle définira des orientations majeures : une augmentation des budgets de la recherche, des salaires et des bourses de chercheurs.

Environ 32000 personnes travaillent aujourd’hui au CNRS en collaboration avec des universités, des laboratoires privés et d’autres organisations

À sa démission, Jean Perrin lui succède. Avec son image de scientifique hirsute, le sexagénaire « déploya aussitôt la fougue d’un jeune homme, l’enthousiasme d’un débutant, non pour les honneurs, mais pour les moyens d’action qu’ils fournissaient », note dans ses mémoires Jean Zay, le très jeune ministre de l’éducation nationale d’alors. Après quatre ans de réalisations, dont la création de laboratoires comme l’Institut d’astrophysique de Paris, le décret fondant le CNRS est publié en octobre 1939. Six semaines après le début de la deuxième guerre mondiale, Jean Perrin annonce : « Il n’est pas de science possible où la pensée n’est pas libre, et la pensée ne peut pas être libre sans que la conscience soit également libre. On ne peut pas imposer à la chimie d’être marxiste, et en même temps favoriser le développement des grands chimistes ; on ne peut pas imposer à la physique d’être cent pour cent aryenne et garder sur son territoire le plus grand des physiciens… Chacun de nous peut bien mourir, mais nous voulons que notre idéal vive. »

La mission du CNRS est encore aujourd’hui d’« identifier, effectuer ou faire effectuer, seul ou avec ses partenaires, toutes les recherches présentant un intérêt pour la science ainsi que pour le progrès technologique, social et culturel du pays ». Environ 32 000 personnes, dont 11 000 chercheurs, travaillent au CNRS en collaboration avec les universités, d’autres organismes ou des laboratoires privés. La plupart des 1100 laboratoires du CNRS sont gérés en cotutelle avec un établissement partenaire Ils accueillent du personnel CNRS et, dans la majorité des cas, des enseignants-chercheurs. Ces unités mixtes de recherche, dont le statut date de 1966, constituent les briques de la recherche française et permettent de mener des recherches pointues tout en restant proche de l’enseignement et des étudiants.

L’évolution de la physique nucléaire et des hautes énergies

Placé sous la tutelle du ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la recherche et de l’innovation, le CNRS est le plus grand organisme de recherche en France. Avec un budget annuel de 3,4 milliards d’euros, il couvre l’ensemble des recherches scientifiques, des humanités aux sciences de la nature et de la vie, de la matière et de l’Univers, de la recherche fondamentale aux applications. Les disciplines sont organisées en dix instituts thématiques qui gèrent les programmes scientifiques ainsi qu’une importante partie des investissements dans les infrastructures de recherche, comme les contributions de ses laboratoires aux expériences du CERN. Il joue un rôle de coordination, en particulier à travers ses trois instituts nationaux, dont l’IN2P3 (Institut national de physique nucléaire et physique des particules) aux cotés des instituts nationaux des sciences de l’Univers et des mathématiques.

À la création du CNRS, la physique française est au meilleur niveau mondial : Irène et Frédéric Joliot-Curie, Jean Perrin, Louis de Broglie, Pierre Auger sont parmi les noms entrés dans l’histoire de la discipline. Le laboratoire de Frédéric Joliot-Curie au Collège de France joue un rôle important grâce à son cyclotron, de même que l’Institut du radium de Irène Joliot-Curie, le laboratoire de Louis Leprince-Ringuet à l’École polytechnique, ou encore celui de Jean Thibaud à Lyon. Des équipements, des boursiers et du personnel technique, des chaires en physique nucléaire dans les universités et les grandes écoles sont financés par le tout jeune CNRS. Avec la guerre, une véritable césure se produit : les chercheurs s’exilent ou tentent de continuer à faire fonctionner leurs laboratoires dans un isolement certain.

Fort de son engagement dans la résistance, Fréderic Joliot-Curie, prend la direction du CNRS en août 1944 et œuvre pour que la France rattrape le retard accumulé pendant la guerre, notamment en physique nucléaire. Après le lancement des bombes atomiques sur Hiroshima et Nagasaki, le Général de Gaulle demande à Frédéric Joliot-Curie et à Raoul Dautry, ministre de la reconstruction et de l’urbanisme, de mettre en place le Commissariat à l’énergie atomique (CEA). Dans l’idée de Joliot-Curie, cet organisme allait rassembler et coordonner toutes les recherches fondamentales de physique nucléaire, y compris celles des laboratoires universitaires. Dès 1946, les grands noms rejoignent le CEA : Pierre Auger, Irène Joliot-Curie, Francis Perrin, Lew Kowarski. Le CNRS se préoccupe alors peu de ce domaine. En 1947, la décision est prise de construire un centre à Saclay qui couple les recherches fondamentales et appliquées sur ce sujet. André Berthelot y dirigera le service de physique nucléaire et y installera plusieurs accélérateurs.

La création du CERN

Dans les années 1950, les physiciens français jouent un rôle important dans la création du CERN : Louis de Broglie, le premier scientifique de renom à demander la création d’un laboratoire multinational lors d’une conférence de Lausanne en 1949, Pierre Auger qui dirige le département des sciences exactes et naturelles de l’UNESCO, Raoul Dautry, l’administrateur général du CEA, Francis Perrin, haut-commissaire, et Lew Kowarski, l’un des premiers employés du CERN et qui deviendra plus tard le directeur des services techniques et scientifiques. On lui doit la construction de la première chambre à bulles au CERN et l’introduction des ordinateurs. Frédéric Joliot-Curie, révoqué en 1950 de ses fonctions au CEA pour ses convictions politiques, est quant à lui très affecté de ne pas être nommé au Conseil du CERN, à l’inverse de Francis Perrin, qui lui a succédé au CEA. Conscient des potentialités du CERN, Louis Leprince-Ringuet réoriente les recherches de ses équipes portant sur les rayons cosmiques vers les accélérateurs. Il deviendra le premier président français du Comité des directives scientifiques (SPC) en 1964 et son laboratoire jouera un rôle important dans l’implication des physiciens français au CERN.

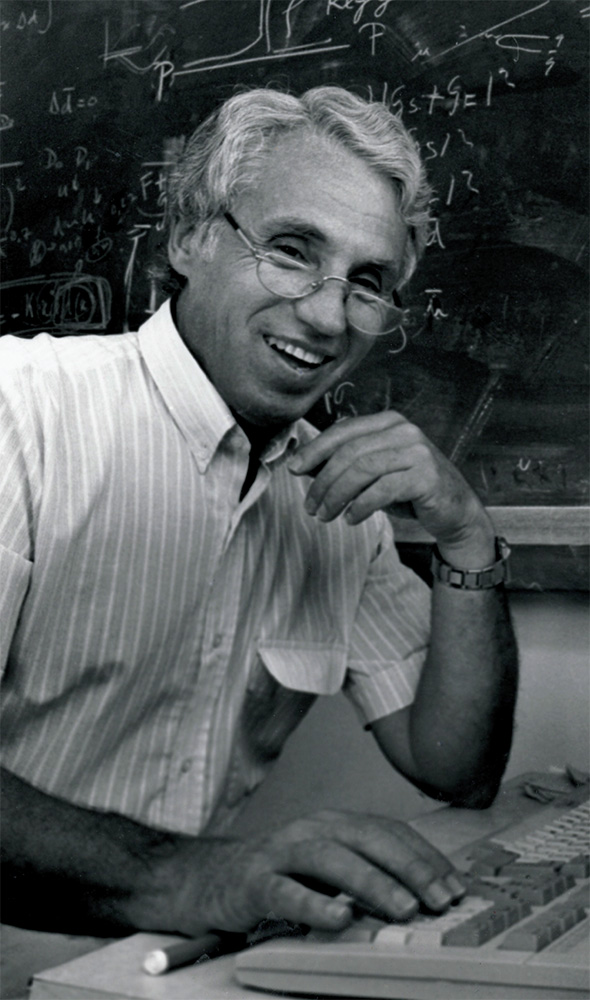

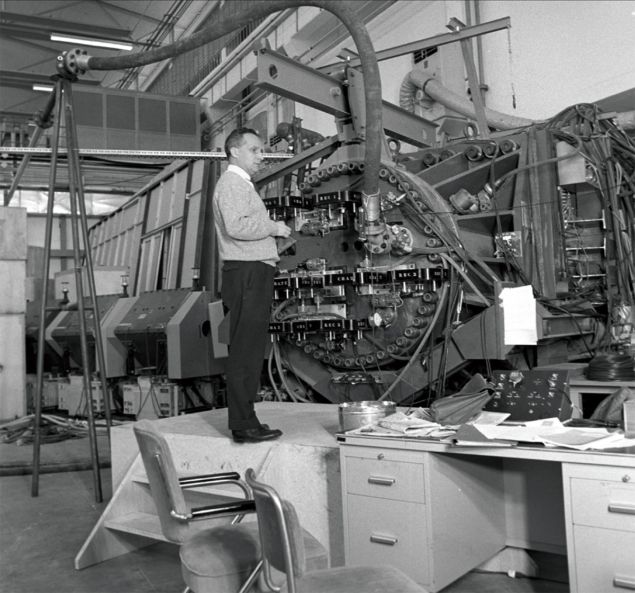

Une autre recrue du CNRS de l’après-guerre fera également parler de lui au CERN : Georges Charpak. Admis au CNRS comme chercheur en 1948, il réalise sa thèse sous la direction de Frédéric Joliot-Curie. Alors que ce dernier veut l’orienter vers la physique nucléaire, il choisit son propre sujet : les détecteurs. En 1963, il est recruté par Leon Lederman au CERN. La suite est connue : il met au point la chambre proportionnelle « multi-fils » qui remplace les chambres à bulles et les chambres à étincelles en permettant un traitement numérique des données. L’invention lui vaut le prix Nobel de physique en 1992.

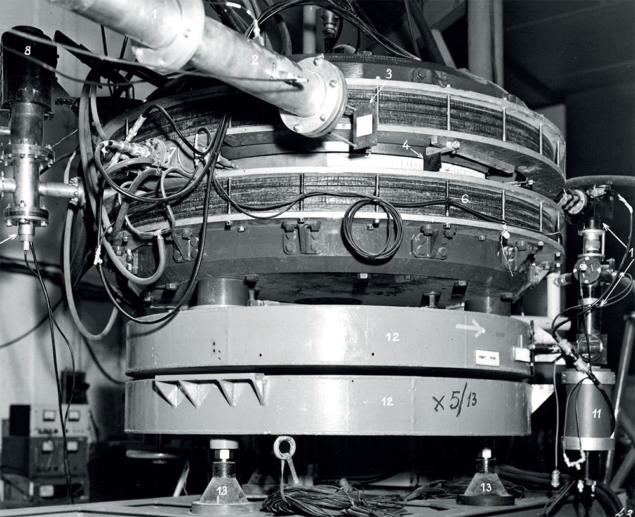

A son retour au Collège de France, Frédéric Joliot-Curie s’engage auprès d’Irène dans la création du campus d’Orsay. Avec la perspective de nouvelles installations au CERN, des infrastructures en France leur semblent nécessaires pour permettre aux physiciens français de se former et de préparer leurs expériences au CERN. « Contribuer à créer et à faire vivre le CERN en laissant s’éteindre la recherche fondamentale française en physique nucléaire serait agir contre les intérêts de notre pays et contre ceux de la science », écrit Irène Joliot-Curie dans « Le Monde ». Le gouvernement de Pierre Mendès France donne une priorité à la recherche et alloue en 1954 des crédits pour la construction de deux accélérateurs, un synchrocyclotron dans l’Institut du radium d’Irène Joliot-Curie, et un accélérateur linéaire pour le Laboratoire de physique de Yves Rocard à l’École normale supérieure. Irène Joliot-Curie obtient les terrains nécessaires à Orsay pour la construction de l’Institut de physique nucléaire (IPNO) et le Laboratoire de l’accélérateur linéaire (LAL). Irène Joliot-Curie ne verra pas le nouveau laboratoire et c’est Fréderic Joliot-Curie qui devient le premier directeur de l’IPNO et Hans Halban, rappelé d’Angleterre, prend la direction du LAL. Ces deux instituts emblématiques jouent encore un rôle majeur pour les contributions françaises au CERN.

L’éclosion des laboratoires

Pendant les années 1950-1960, le CNRS connaît un fort développement et d’autres laboratoires de physique nucléaire et des hautes énergies sont créés. Un accélérateur Cockroft-Walton construit pendant la guerre à Strasbourg par les Allemands sera le germe du Centre de recherches nucléaires, dirigé par Serge Gorodetzky. Créée en 1947, la chaire de Maurice Scherer en physique nucléaire à Caen devient le Laboratoire de physique corpusculaire. L’un de ses premiers thésards, Louis Avan, fondera un laboratoire du même nom à Clermont-Ferrand en 1959. A Grenoble, Louis Néel pose les fondations d’une importante activité de recherche en physique et le CEA y installera le Centre d’études nucléaires en 1956. En 1967, le réacteur de recherche franco-allemand de l’Institut Laue-Langevin y est construit. La même année, l’Institut des sciences nucléaires de Grenoble voit le jour : il accueillera un cyclotron, utilisé en particulier pour produire des radio-isotopes en médecine. Son directeur, Jean Yoccoz, sera l’un des futurs directeurs de l’IN2P3. Le Centre d’études nucléaires de Bordeaux-Gradignan s’installe dans un ancien château bordelais en 1969.

Les physiciens de ces laboratoires participent activement aux expériences au CERN, bénéficiant en particulier d’une mobilité facilitée par le CNRS. Parmi eux, Bernard Gregory, du laboratoire de Leprince-Ringuet, s’oriente, en vue de la prochaine mise en service du Synchrotron à protons (PS) du CERN, vers la construction à Saclay d’une grande chambre à bulles à hydrogène liquide de 81 centimètres. Elle produira plus de dix millions de clichés d’interactions de particules, distribués à travers toute l’Europe. En 1965, Bernard Gregory est désigné directeur général du CERN. Cinq ans plus tard, il succède à Louis Leprince-Ringuet à la direction du laboratoire de l’École polytechnique, puis devient directeur général du CNRS. Il est élu président du Conseil en 1977.

Gérer l’expansion

Dans les années 1960, les équipements de recherche deviennent si imposants qu’émerge au sein du CNRS l’idée de créer des instituts nationaux pour coordonner les ressources et les activités des laboratoires. Le directeur du LAL, André Blanc-Lapierre, milite pour la création d’un institut national de physique nucléaire et de physique des particules, à l’instar de l’INFN italien fondé en 1951. Il s’agit d’organiser les moyens alloués aux différents laboratoires par le CNRS, les universités et le CEA : les discussions entre les partenaires commencent.

Parallèlement, un autre débat anime les physiciens français. Après la construction en 1958 de l’accélérateur de protons SATURNE de 3 GeV au CEA à Saclay et, en 1962, de l’accélérateur linéaire à électrons de 1,3 GeV au LAL à Orsay, et la construction du collisionneur électron-positron ACO, les esprits se divisent sur la construction d’une machine nationale qui complèterait les capacités expérimentales du CERN et renforcerait la communauté scientifique française. Deux propositions sont en lice : une machine à protons et une machine à électrons. D’autant qu’en Europe d’autres machines sont sorties de terre. En Italie, le collisionneur électron-positon AdA est suivi en 1969 par ADONE. À Hambourg en Allemagne, le synchrotron à électrons DESY démarre en 1964.

La France en revanche donne la priorité à la construction européenne avec le CERN. Aucun des deux projets proposés ne voit donc le jour. Jean Teillac, successeur de Frédéric Joliot-Curie à la tête de l’IPNO, fonde l’IN2P3 en 1971, regroupant les laboratoires du CNRS et des universités. Il faudra attendre 1975 pour que le CEA et l’IN2P3 décident de construire ensemble à Caen une machine nationale, le Grand accélérateur national d’ions lourds (GANIL), spécialisé en physique nucléaire. Bien que les laboratoires concernés du CEA ne fassent pas partie de l’IN2P3, les collaborations entre les physiciens des deux organismes sont importantes.

Ainsi, André Lagarrigue, directeur du LAL depuis 1969, propose la construction d’une nouvelle chambre à bulles, Gargamelle, sur un faisceau de neutrinos du CERN. Le scientifique avait exploré auparavant à l’École polytechnique la faisabilité de chambres à bulles contenant des liquides lourds au lieu de l’hydrogène, favorisant les interactions avec des neutrinos. Après sa construction au CEA Saclay, la chambre remplie de fréon liquide est installée au CERN et décèlera en 1973 les courants neutres. Une découverte majeure, certainement nobélisable si Lagarrigue n’avait pas succombé à une crise cardiaque en 1975.

Depuis lors

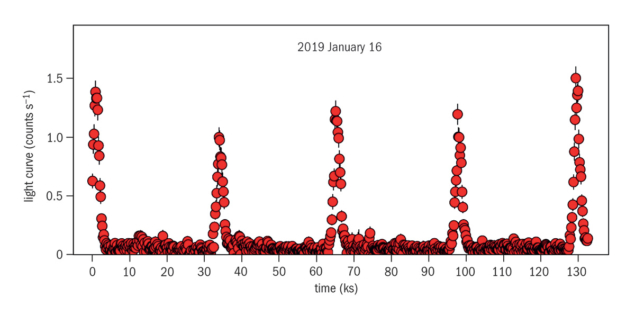

L’IN2P3 compte aujourd’hui une vingtaine de laboratoires, environ 3200 personnes dont 1000 chercheurs et enseignants-chercheurs dans les domaines de la physique nucléaire, des particules et des astroparticules ainsi qu’en cosmologie. L’Institut contribue au développement d’accélérateurs, de détecteurs et d’instruments d’observation et leurs applications. Son centre de calcul à Lyon joue un rôle important dans le traitement et le stockage de grands volumes de données, hébergeant par ailleurs des infrastructures numériques d’autres disciplines.

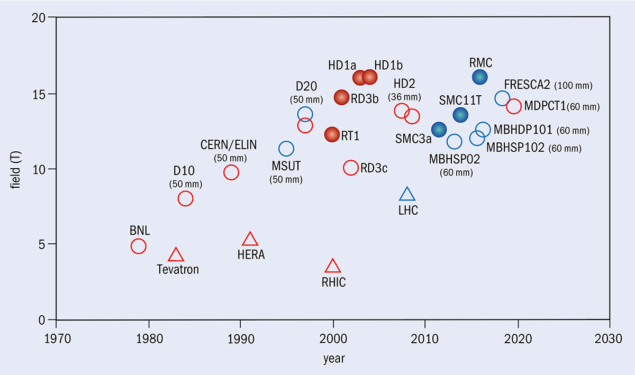

Les liens avec le CERN sont forts à travers des nombreux projets et expériences : la découverte des bosons W et Z par UA1 et UA2, le LEP avec des contributions à ALEPH, DELPHI et L3, la découverte du boson de Higgs par ATLAS et CMS au LHC, LHCb et ALICE, la physique des neutrinos, la violation de CP, les expériences sur l’antimatière, ainsi que la physique nucléaire. Les collaborations impliquent d’autres instituts du CNRS comme l’INP (Institut de physique), auquel sont rattachés des théoriciens, ainsi que les spécialistes de la physique quantique et des lasers, ou encore les recherches des champs magnétiques intenses.

Et la suite ? Les futurs projets du CERN sont en discussion à l’occasion de la mise à jour de la stratégie européenne pour la physique des particules. Ils offrent la possibilité de faire émerger de nouvelles collaborations entre le CERN et le CNRS, en physique mais aussi en ingénierie, en calcul, dans les applications biomédicales ou, pourquoi pas, en sciences humaines. Sans aucun doute, de la synergie entre ces deux organismes porteurs d’une richesse scientifique exceptionnelle, de nouvelles recherches passionnantes verront le jour !

- La version anglaise de cet article est disponible ici.