In 1969 many weak amplitudes could be accurately calculated with a model of just three quarks, and Fermi’s constant and the Cabibbo angle to couple them. One exception was the remarkable suppression of strangeness-changing neutral currents. John Iliopoulos, Sheldon Lee Glashow and Luciano Maiani boldly solved the mystery using loop diagrams featuring the recently hypothesised charm quark, making its existence a solid prediction in the process. To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of their insight, the trio were guests of honour at an international symposium at the T. D. Lee Institute at Shanghai Jiao Tong University on 29 October, 2019.

The UV cutoff needed in the three-quark theory became an estimate of the mass of the fourth quark

The Glashow-Iliopoulos-Maiani (GIM) mechanism was conceived in 1969, submitted to Physical Review D on 5 March 1970, and published on 1 October of that year, after several developments had defined a conceptual framework for electroweak unification. These included Yang-Mills theory, the universal V−A weak interaction, Schwinger’s suggestion of electroweak unification, Glashow’s definition of the electroweak group SU(2)L×U(1)Y, Cabibbo’s theory of semileptonic hadron decays and the formulation of the leptonic electroweak gauge theory by Weinberg and Salam, with spontaneous symmetry breaking induced by the vacuum expectation value of new scalar fields. The GIM mechanism then called for a fourth quark, charm, in addition to the three introduced by Gell-Mann, such that the first two blocks of the electroweak theory are made each by one lepton and one quark doublet, [(νe, e), (u, d)] and [(νµ, µ), (c, s)]. Quarks u and c are coupled by the weak interaction to two superpositions of the quarks d and s: u ↔ dC , with dC the Cabibbo combination dC = cos θC d + sin θC s, and c ↔ sC , with sC the orthogonal combination. In subsequent years, a third generation, [(ντ, τ ), (t, b)] was predicted to describe CP violation. No further generations have been observed yet.

Problem solved

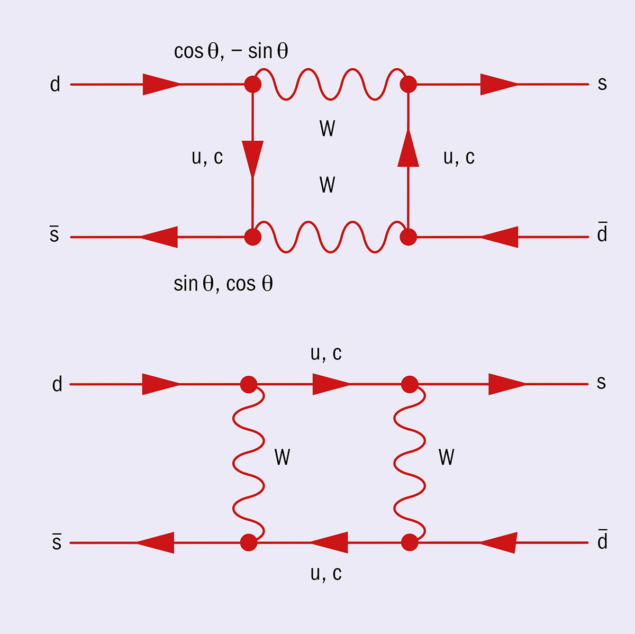

The GIM mechanism was the solution to a problem arising in the simplest weak interaction theory with one charged vector boson coupled to the Cabibbo currents. As pointed out in 1968, strangeness-changing neutral-current processes, such as KL → µ+µ− and K0 – K0 mixing, are generated at one loop with amplitudes of order G sinθC cosθC (GΛ2), where G is the Fermi constant, Λ is an ultraviolet cutoff, and GΛ2 (dimensionless) is the first term in a perturbative expansion which could be continued to take higher order diagrams into account. To comply with the strict limits existing at the time, one had to require a surprisingly small value of the cutoff, Λ, of 2 − 3 GeV, to be compared with the naturally expected value: Λ = G-1/2 ~ 300 GeV. This problem was taken seriously by the GIM authors, who wrote that “it appears necessary to depart from the original phenomenological model of weak interactions”.

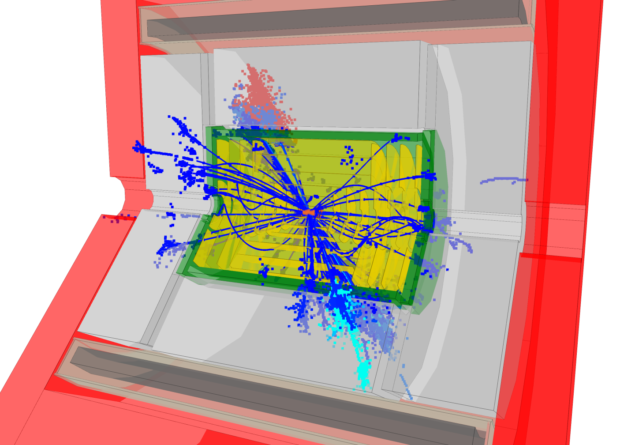

To sidestep this problem, Glashow, Iliopoulos and Maiani brought in the fourth “charm” quark, already introduced by Bjorken, Glashow and others, with its typical coupling to the quark combination left alone in the Cabibbo theory: c ↔ sC = − sinθC d + cosθC s. Amplitudes for s → d with u or c on the same fermion line would cancel exactly for mc = mu, suggesting a more natural means to suppress strangeness-changing neutral-current processes to measured levels. For mc >> mu, a residual neutral-current effect would remain, which, by inspection, and for dimensional reasons, is of order G sinθC cos θC (Gmc2). This was a real surprise: the “small” UV cutoff needed in the simple three-quark theory became an estimate of the mass of the fourth quark, which was indeed sufficiently large to have escaped detection in the unsuccessful searches for charmed mesons that had been conducted in 1960s. With the two quark doublets included, a detailed study of strangeness changing neutral current processes gave mc ∼ 1.5 GeV, a value consistent with more recent data on the masses of charmed mesons and baryons. Another aspect of the GIM cancellation is that the weak charged currents make an SU(2) algebra together with a neutral component that has no strangeness changing terms. Thus, there is no difficulty to include the two quark doublets in the unified electroweak group SU(2)L×U(1)Y of Glashow, Weinberg and Salam. The 1970 GIM paper noted that “in contradistinction to the conventional (three-quark) model, the couplings of the neutral intermediary – now hypercharge conserving – cause no embarrassment.”

The GIM mechanism has become a cornerstone of the Standard Model and it gives a precise description of the observed flavour changing neutral current processes for s and b quarks. For this reason, flavour-changing neutral currents are still an important benchmark and give strong constraints on theories that go beyond the Standard Model in the TeV region.