As part of the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a team led by physicists and engineers from the LHCb collaboration has proposed a design for a novel ventilator. The High Energy Ventilator (HEV) is based on components which are simple and cheap to source, complies with hospital standards, and supports the most requested ventilator-operation modes, writes the newly formed HEV collaboration. Though the system needs to be verified by medical experts before it can enter use, in the interests of rapid development the HEV team has presented the design to generate feedback, corrections and support as the project progresses. The proposal is one of several recent and rapidly developing efforts launched by high-energy physicists to help combat COVID-19.

The majority of people who contract COVID-19 suffer mild symptoms, but in some cases the disease can cause severe breathing difficulties and pneumonia. For such patients, the availability of ventilators that deliver oxygen to the lungs while removing carbon dioxide could be the difference between life and death. Even with existing ventilator suppliers ramping up production, the rapid rise in COVID-19 infections is causing a global shortage of devices. Multiple efforts are therefore being mounted by governments, industry and academia to meet the demand, with firms which normally operate in completely different sectors – such as Dyson and General Motors – diverting resources to the task.

There are many proposals on the market, but we don’t know now which ones will in the end make a difference, so everything which could be viable should be pursued

Paula Collins

HEV was born out of discussions in the LHCb VELO group, when lead-designer Jan Buytaert (CERN) realised that the systems which are routinely used to supply and control gas at desired temperatures and pressures in particle-physics detectors are well matched to the techniques required to build and operate a ventilator. The team started from a set of guidelines recently drawn up by the UK government’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency regarding rapidly manufactured ventilator systems, and was encouraged by a 3D-printed prototype constructed at the University of Liverpool in response to these guidelines. The driving pressure of ventilators — which must be able to handle situations of rapidly changing lung compliance, and potential collapse and consolidation — is a crucial factor for patient outcomes. The HEV team therefore aimed to produce a patient-safety-first design with a gentle and precise pressure control that is responsive to the needs of the patient, and which offers internationally recommended operation modes.

As the HEV team comprises physicists, not medics, explains HEV collaborator Paula Collins of CERN, it was vital to get the relevant input from the very start. “Here we have benefitted enormously from the experience and knowledge of CERN’s HSE [occupational health & safety and environmental protection] group for medical advice, conformity with applicable legislation and health-and-safety requirements, and the working relationship with local hospitals. The team is also greatly supported from other CERN departments, in particular for electronic design and the selection of the best components for gas manipulation. During lockdown, the world is turning to remote connection, and we were very encouraged to find that it was possible in a short space of time to set up an online chat group of experienced anesthesiologists and respiratory experts from Australia, Belgium, Switzerland and Germany, which sped up the design considerably.”

Stripped-down approach

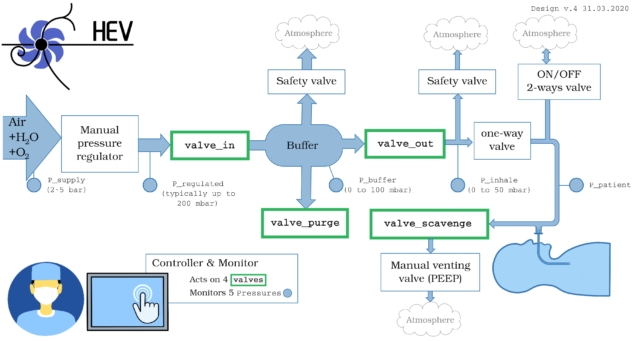

The HEV concept relies on easy-to-source components, which include electro-valves, a two-litre buffer container, a pressure regulator and several pressure sensors. Embedded components — currently Arduino and Rasbperry Pi — are being used to address portability requirements. The unit’s functionality will be comprehensive enough to provide long-term support to patients in the initial or recovery phases, or with more mild symptoms, freeing up high-end machines for the most serious intensive care, explains Collins: “It will incorporate touchscreen control intuitive to use for qualified medical personnel, even if they are not specialists in ventilator use, and it will include extensive monitoring and failsafe mechanisms based on CERN’s long experience in this area, with online training to be developed.”

The first stage of prototyping, which was achieved at CERN on 27 March, was to demonstrate that the HEV working principle is sound and allows the ventilator to operate within the required ranges of pressure and time. The desired physical characteristics of the pressure regulators, valves and pressure sensors are now being refined, and the support of clinicians and international organisations is being harnessed for further prototyping and deployment stages. “This is a device which has patient safety as a major priority,” says HEV collaborator Themis Bowcock of the University of Liverpool. “It is aimed at deployment round the world, also in places that do not necessarily have state-of-the-art facilities.”

Complementary designs

The HEV concept complements another recent ventilator proposal, initiated by physicists in the Global Argon Dark Matter Collaboration. The Mechanical Ventilator Milano (MVM) is optimised to permit large-scale production in a short amount of time and at a limited cost, also relying on off-the-shelf components that are readily available. In contrast to the HEV design, which aims to control pressure by alternately filling and emptying a buffer, the MVM project regulates the flow of the incoming mixture of oxygen and air via electrically controlled valves. The proposal stems from a cooperation of particle- and nuclear-physics laboratories and universities in Canada, Italy and the US, with an initial goal to produce up to 1000 units in each of the three countries while the interim certification process is ongoing. Clinical requirements are being developed with medical experts, and detailed testing and qualification of the first prototype is presently underway with a breathing simulator at Ospedale San Gerardo in Monza, Italy.

Sharing several common ideas with the MVM principle, but with emphasis on further reducing the number and specificity of components to make construction possible during times of logistical disruption, a team led by particle physicists at the Laboratory of Instrumentation and Experimental Particles Physics in Portugal has also posted a proof-of-concept study for a ventilator on arXiv. All ventilator designs are evolving quickly and require further development before they can be deployed in hospitals.

“It is difficult to conceive a project which goes all the way and includes all the bells and whistles needed to get it into the hospital, but this is our firm goal,” says Collins. “After one week we had a functioning demonstrator, after two weeks we aim to test on a medical mechanical lung and to start prototyping in the hospital context. We find ourselves in a unique and urgent situation where there are many proposals on the market, but we don’t know now which ones will in the end make a difference, so everything which could be viable should be pursued.”