Nuclear physics is as wide-ranging and relevant today as ever before in the century-long history of the subject. Researchers study exotic systems from hydrogen-7 to the heaviest nuclides at the boundaries of the nuclear landscape. By constraining the nuclear equation of state using heavy-ion collisions, they peer inside stars in controlled laboratory tests. By studying weak nuclear processes such as beta decays, they can even probe the Standard Model of particle physics. And this is not to mention numerous applications in accelerator-based atomic and condensed-matter physics, radiobiology and industry. These nuclear-physics research areas are just a selection of the diverse work done at the Grand Accélérateur National d’Ions Lourds (GANIL), in Caen, France.

GANIL has been operating since 1983, initially using four cyclotrons, with a fifth Cyclotron pour Ions de Moyenne Energie (CIME) added in 2001. The latter is used to reaccelerate short-lived nuclei produced using beams from the other cyclotrons – the Système de Production d’Ions Radioactifs en Ligne (SPIRAL1) facility. The various beams produced by these cyclotrons drive eight beams with specialised instrumentation. Parallel operation allows the running of three experiments simultaneously, thereby optimising the available beam time. These facilities enable both high-intensity stable-ion beams, from carbon-12 to uranium-238, and lower intensity radioactive-ion beams of short-lived nuclei, with lifetimes from microseconds to milliseconds, such as helium-6, helium-8, silicon-42 and nickel-68. Coupled with advanced detectors, all these beams allow nuclei to be explored in terms of excitation energy, angular momentum and isospin.

The new SPIRAL2 facility, which is currently being commissioned, will take this work into the next decade and beyond. The most recent step forward is the beam commissioning of a new superconducting linac – a major upgrade to the existing infrastructure. Its maximum beam intensity of 5 mA, or 3 × 1016 particles per second, is more than two orders of magnitude higher than at the previous facility. The new beams and state-of-the-art detectors will allow physicists to explore phenomena at the femtoscale right up to the astrophysical scale.

Landmark facility

SPIRAL2 was approved in 2005. It now joins a roster of cutting-edge European nuclear-physics-research facilities which also features the Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research (FAIR), in Darmstadt, Germany, ISOLDE and nTOF at CERN, and the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Russia. Due to their importance in the European nuclear-physics roadmap, SPIRAL2 and FAIR are both now recognised as European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures (ESFRI) Landmark projects, alongside 11 other facilities, including accelerator complexes such as the European X-Ray Free-Electron Laser, and telescopes such as the Square Kilometre Array.

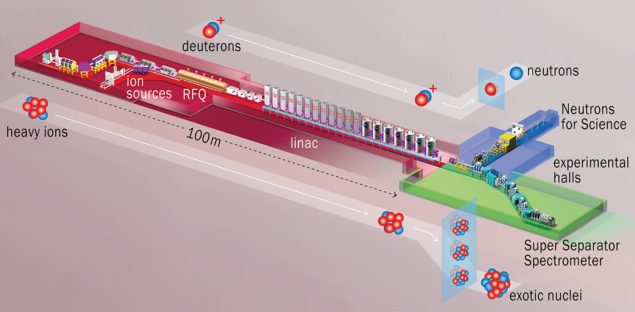

Construction began in 2011. The project was planned in two phases: the construction of a linac for very-high-intensity stable beams, and the associated experimental halls (see “High intensity” figure); and infrastructure for the reacceleration of short-lived fission fragments, produced using deuteron beams on a uranium target through one of the GANIL cyclotrons. Though the second phase is currently on hold, SPIRAL2’s new superconducting linac is now in a first phase of commissioning.

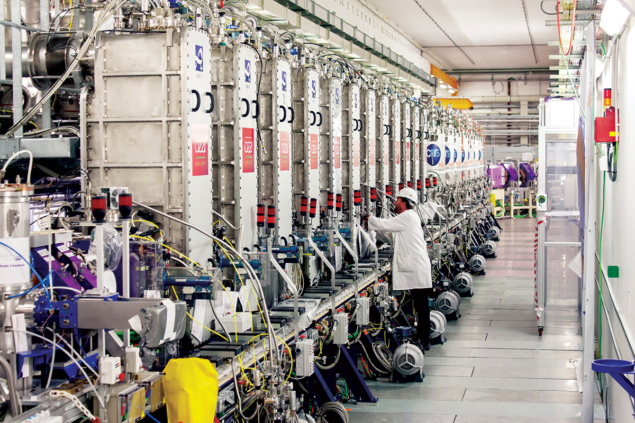

Most linacs are optimised for a beam with specific characteristics, which is supplied time and again by an injector. The particle species, velocity profile of the particles being accelerated and beam intensity all tend to be fixed. By tuning the phase of the electric fields in the accelerating structures, charged particles surf on the radio-frequency waves in the cavities with optimal efficiency in a single pass. Though this is the case for most large projects, such as Linac4 at CERN, the Spallation Neutron Source (SNS) in the US and the European Spallation Source in Sweden, SPIRAL2’s linac (see “Multitasking” figure) has been designed for a wide range of ions, energies and intensities.

The multifaceted physics criteria called for an original design featuring a compact multi-cryostat structure for the superconducting cavities, which was developed in collaboration with fellow French national organisations CEA and CNRS. Though the 19 cryomodules are comparable in number to the 23 employed by the larger and more powerful SNS accelerator, the new SPIRAL2 linac has far fewer accelerating gaps. On the other hand, compared to normal-conducting cavities such as those used by Linac4, the power consumption of the superconducting structures at SPIRAL2 is significantly lower, and the linac conforms to additional constraints on the cryostat’s design, operation and cleanliness. The choice of superconducting rather than room-temperature cavities is ultimately linked not only to the need for higher beam intensities and energies, but also to the potential for the larger apertures needed to reduce beam losses.

SPIRAL2 joins a roster of cutting-edge European nuclear-physics-research facilities

Beams are produced using two specialised ion sources. At 200 kW in continuous-wave (CW) mode, the beam power is high enough to make a hole in the vacuum chamber in less than 35 µs, placing additional severe restrictions on the beam dynamics. The operation of high beam intensities, up to 5 mA, also causes space-charge effects that need to be controlled to avoid a beam halo which could activate accelerator components and generate neutrons – a greater difficulty in the case of deuteron beams.

For human safety and ease of technical maintenance, beam losses need to be kept below 1 W/m. Here, the SPIRAL2 design has synergies with several other high-power accelerators, leading to improvements in the design of quarter-wave resonator cavities. These are used at heavy-ion accelerators such as the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams in the US and the Rare Isotope Science Project in Korea; for producing radioactive-ion beams and improving beam dynamics at intense-light particle accelerators worldwide; for producing neutrons at the International Fusion Materials Irradiation Facility, the ESS, the Myrrha Multi-purpose Hybrid Research Reactor for High-tech Applications, and the SNS; and for a large range of studies relating to materials properties and the generation of nuclear power.

Beam commissioning

Initial commissioning of the linac began by sending beams from the injector to a dedicated system with various diagnostic elements. The injector was successfully commissioned with a range of CW beams, including a 5 mA proton beam, a 2 mA alpha-particle beam, a 0.8 mA oxygen–ion beam and a 25 µA argon–ion beam. In each case, almost 100% transmission was achieved through the radio-frequency quadrupoles. Components of the linac were installed, the cryomodules cooled to liquid-helium temperatures (4.5 K), and the mechanical stability required to operate the 26 superconducting cavities at their design specifications demonstrated.

As GANIL is a nuclear installation, the injection of beams into the linac required permission from the French nuclear-safety authority. Following a rigorous six-year authorisation process, commissioning through the linac began in July 2019. An additional prerequisite was that a large number of safety systems be validated and put into operation. The key commissioning step completed so far is the demonstration of the cavity performance at 8 MV/m – a competitive electric field well above the required 6.5 MV/m. The first beam was injected into the linac in late October 2019. The cavities were tuned and a low-intensity 200 µA beam of protons accelerated to the design value of 33 MeV and sent to a first test experiment in the neutrons for science (NFS) area. A team from the Nuclear Physics Institute in Prague irradiated copper and iron targets and the products formed in the reaction were transported by a fast-automatic system 40 m away, where their characteristic γ-decay was measured. Precise measurements of such cross-sections are important in order to benchmark safety codes required for the operation of nuclear reactors.

SPIRAL2 is now moving towards its design power by gradually increasing the proton beam current and subsequently the duty cycle of the beam – the ratio of pulse duration to the period of the waveform. A similar procedure with alpha particles and deuteron beams will then follow. Physics programmes will begin in autumn next year.

Future physics

With the new superconducting linac, SPIRAL2 will provide intense beams from protons to nickel – up to 14.5 MeV/A for heavy ions – and continuous and quasi-mono energetic beams of neutrons up to 40 MeV. With state-of-the-art instrumentation such as the Super Separator Spectrometer (S3), the charged particle beams will allow the study of very rare events in the intense background of the unreacted beam with a signal to background fraction of 1 in 1013. The charged particle beams will also characterise exotic nuclei with properties very different from those found in nature. This will address questions related to heavy and super-heavy element/isotope synthesis at the extreme boundaries of the periodic table, and the properties of nuclei such as tin-100, which have the same number of neutrons and protons – a far cry from naturally existing isotopes such as tin-112 and tin-124. Here, ground-state properties such as the mass of nuclei must be measured with a precision of one part in 109 – a level of precision equivalent to observing the addition of a pea to the weight of an Airbus A380. SPIRAL2’s low-energy experimental hall for the disintegration, excitation and storage of radioactive ions (DESIR), which is currently under construction, will further facilitate detailed studies of the ground-state properties of exotic nuclei fed both by S3 and SPIRAL1, the existing upgraded reaccelerated exotic-beams facility. The commissioning of S3 is expected in 2023 and experiments in DESIR in 2025. In parallel, a continuous improvement in the SPIRAL2 facility will begin with the integration of a new injector to substantially increase the intensity of heavy-ion beams.

Properties must be measured with a level of precision equivalent to observing the addition of a pea to the weight of an Airbus A380

Thanks to its very high neutron flux – up to two orders of magnitude higher, in the energy range between 1 and 40 MeV, than at facilities like LANSCE at Los Alamos, nTOF at CERN and GELINA in Belgium – SPIRAL2 is also well suited for applications such as the transmutation of nuclear waste in accelerator-driven systems, the design of present and next-generation nuclear reactors, and the effect of neutrons on materials and biological systems. Light-ion beams from the linac, including alpha particles and lithium-6 and lithium-7 impinging on lead and bismuth targets, will also be used to investigate more efficient methods for the production of certain radioisotopes for cancer therapy.

Developments at SPIRAL2 are quickly moving forwards. In September, the control of the full emittance and space–charge effects was demonstrated – a crucial step to reach the design performance of the linac – and a first neutron beam was produced at NFS, using proton beams. The future looks bright. With the new SPIRAL2 superconducting linac now supplementing the existing cyclotrons, GANIL provides an intensity and variety of beams that is unmatched in a single laboratory, making it a uniquely multi-disciplinary facility in the world today.