Hans Joachim Specht: Scientist and Visionary, edited by Sanja Damjanovic, Volker Metag, Jürgen Schukraft and Hans Joachim Specht, Springer Nature

Across a career that accompanied the emergence of heavy-ion physics at CERN, Hans Joachim Specht was often a decisive voice in shaping the experimental agenda and the institutional landscape in Europe. Before he passed away last May, he and fellow editors Sanja Damjanovic (GSI), Volker Metag (University of Giessen) and Jürgen Schukraft (Yale University) finalised the manuscript for Scientist and Visionary – a new biographical work that offers both a retrospective on Specht’s wide-ranging scientific contributions and a snapshot of four decades of evolving research at CERN, GSI and beyond.

Precision and rigour

Specht began his career in nuclear physics under the mentorship of Heinz Maier-Leibnitz at the Technische Universität München. His early work was grounded in precision measurements and experimental rigour. Among his most celebrated early achievements were the discoveries of superheavy quasi-molecules and quasi-atoms, where electrons can be bound for short times to a pair of heavy ions, and nuclear-shape isomerism, where nuclei exhibit long-lived prolate or oblate deformations. These milestones significantly advanced the understanding of atomic and nuclear structure. Around 1979, he shifted focus, joining the emerging efforts at CERN to explore the new frontier of ultra-relativistic heavy-ion collisions, which was started five years earlier at Berkeley by the GSI-LBL collaboration. It was Bill Willis, one of CERN’s early advocates for high-energy nucleus–nucleus collisions, who helped draw Specht into this developing field. That move proved foundational for both Specht and CERN.

From the early 1980s through to 2010, Specht played leading roles in four CERN nuclear-collision experiments: R807/808 at the Intersecting Storage Rings, and HELIOS, CERES/NA45 and NA60 at the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS). As the book describes, he was instrumental, and not only in their scientific goals, namely to search for the highest temperatures of the newly formed hot, dense QCD matter, exceeding the well established Hagedorn limiting hadron fluid temperature of roughly 160 MeV. The overarching aim was to establish that quasi-thermalised gluon matter and even quark–gluon matter can be created at the SPS. Specht was also involved in the design and execution of these detectors. At the Universität Heidelberg, he built a heavy-ion research group and became a key voice in securing German support for CERN’s heavy-ion programme.

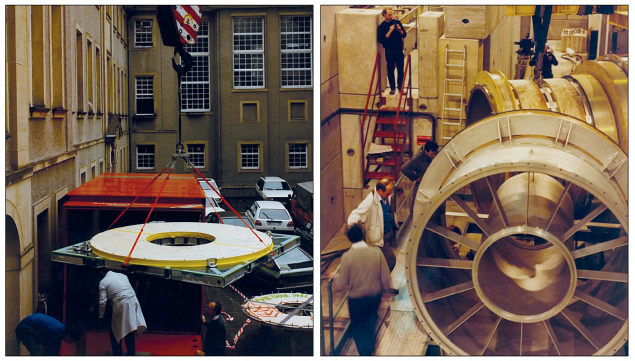

CERES was Specht’s brainchild, and stood out for its bold concept

As spokesperson of the HELIOS experiment from 1984 onwards, Specht gained recognition as a community leader. But it was CERES, his brainchild, that stood out for its bold concept: to look for thermal dileptons using a hadron-blind detector – a novel idea at the time that introduced the concept of heavy-ion collision experiments. Despite considerable scepticism, CERES was approved in 1989 and built in under two years. Its results on sulphur–gold collisions became some of the most cited of the SPS era, offering strong evidence for thermal lepton-pair production, potentially from a quark–gluon plasma – a hot and deconfined state of QCD matter then hypothesised to exist at high temperatures and densities, such as in the early universe. Such high temperatures, above the hadrons’ limiting Hagedorn temperature of 160 MeV, had not yet been experimentally demonstrated at LBNL’s Bevalac and Brookhaven’s Alternating Gradient Synchrotron.

Advising ALICE

In the early 1990s, while CERES was being upgraded for lead–gold runs, Specht co-led a European Committee for Future Accelerators working group that laid the groundwork for ALICE, the LHC’s dedicated heavy-ion experiment. His Heidelberg group formally joined ALICE in 1993. Even after becoming scientific director of GSI in 1992, Specht remained closely involved as an advisor.

Specht’s next major CERN project was NA60, which collided a range of nuclei in a fixed-target experiment at the SPS and pushed dilepton measurements to new levels of precision. The NA60 experiment achieved two breakthroughs: a nearly perfect thermal spectrum consistent with blackbody radiation of temperatures 240 to 270 MeV, some hundred MeV above the previous highest hadron Hagedorn temperature of 160 MeV. Clear evidence of in-medium modification of the ρ meson was observed, due to meson collisions with nucleons and heavy baryon resonances, showing that this medium is not only hot, but also that its net baryon density is high. These results were widely seen as strong confirmation of the lattice–QCD-inspired quark–gluon plasma hypothesis. Many chapter authors, some of whom were direct collaborators, others long-time interpreters of heavy-ion signals, highlight the impact NA60 had on the field. Earlier claims, based on competing hadronic signals for deconfinement, such as strong collective hydrodynamic flow, J/ψ melting and quark recombination, were often also described by hadronic transport theory, without assuming deconfinement.

Specht didn’t limit himself to fundamental research. As director of GSI, he oversaw Europe’s first clinical ion-beam cancer therapy programme using carbon ions. The treatment of the first 450 patients at GSI was a breakthrough moment for medical physics and led to the creation of the Heidelberg Ion Therapy centre in Heidelberg, the first hospital-based hadron therapy centre in Europe. Specht later recalled the first successful treatment as one of the happiest moments of his career. In their essays, Jürgen Debus, Hartmut Eickhoff and Thomas Nilsson outline how Specht steered GSI’s mission into applied research without losing its core scientific momentum.

Specht was also deeply engaged in institutional planning, helping to shape the early stages of the Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research, a new facility to study heavy ion collisions, which is expected to start operations at GSI at the end of the decade. He also initiated plasma-physics programmes, and contributed to the development of detector technologies used far beyond CERN or GSI. In parallel, he held key roles in international science policy, including within the Nuclear Physics Collaboration Committee, as a founding board member of the European Centre for Theoretical Studies in Nuclear Physics in Trento, and at CERN as chair of the Proton Synchrotron and Synchro-Cyclotron Committee, and as a decade-long member of the Scientific Policy Committee.

The book doesn’t shy away from more unusual chapters either. In later years, Specht developed an interest in the neuroscience of music. Collaborating with Hans Günter Dosch and Peter Schneider, he explored how the brain processes musical structure – an example of his lifelong intellectual curiosity and openness to interdisciplinary thinking.

Importantly, Scientist and Visionary is not a hagiography. It includes a range of perspectives and technical details that will appeal to both physicists who lived through these developments and younger researchers unfamiliar with the history behind today’s infrastructure. At its best, the book serves as a reminder of how much experimental physics depends not just on ideas, but on leadership, timing and institutional navigation.

That being said, it is not a typical scientific biography. It’s more of a curated mosaic, constructed through personal reflections and contextual essays. Readers looking for deep technical analysis will find it in parts, especially in the sections on CERES and NA60, but its real value lies in how it tracks the development of large-scale science across different fields, from high-energy physics to medical applications and beyond.

For those interested in the history of CERN, the rise of heavy-ion physics, or the institutional evolution of European science, this is a valuable read. And for those who knew or worked with Hans Specht, it offers a fitting tribute – not through nostalgia, but through careful documentation of the many ways Hans shaped the physics and the institutions we now take for granted.