Theoretical cosmologist Mairi Sakellariadou discusses her goals as president of the European Physical Society and the importance of supporting curiosity-driven research.

Why theoretical cosmology?

I was first trained as a mathematician, and then as a physicist. I’ve always worked at the interface between theory and data, where one of the most interesting things is to test cosmological models inspired by some fundamental theory. For example, you can create a model based on string theory or on a non-perturbative approach to quantum gravity, and then use data to constrain the quantum gravity theory. Today we receive a wealth of data from different kinds of experiments, which allows us to test early-universe models without relying on ad hoc ideas. Although it is not something I directly work on, the current tension in the value of the Hubble constant serves as an example. This of course could be telling us something about new physics, but it seems to me it is more likely to be an issue with the way we interpret data and apply the same models across different scales. Supernovae are taken as “standard candles” when measuring the expansion rate of the universe, for example, and one may wonder how correct this assumption is. It is important to perform systematic studies of the raw data before we rush to new theories.

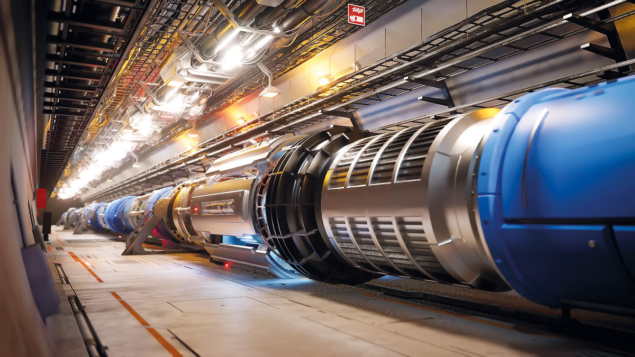

My current work mainly bears on gravitational waves. I am also editor-in-chief of the journal General Relativity and Gravitation. I joined the LIGO collaboration the year of the discovery, studying the implications of gravitational-wave background searches for new physics. I am working on similar studies for the proposed Einstein Telescope. Gravitational waves allow us to test high-energy models beyond the Standard Model at energy scales that are above those that can be reached by accelerators. There are also new results coming from pulsar timing arrays. We live in a time where many exciting results are coming fast.

How big is the European Physical Society, and what led you to be elected president?

The European Physical Society (EPS) is the federation of all national physics societies in Europe. It was founded in 1968 by particle physicist Gilberto Bernardini, who contributed to the foundation of CERN and later became director of the Synchrocyclotron division and directorate member for research.

Several years ago, following the LIGO/Virgo discoveries, I initiated the gravitational physics division of the EPS and, in doing so, entered the EPS council. Then I was elected a member of the executive committee and was eventually contacted to run for election. I admit that I was reluctant at first because it’s another task with a lot of responsibilities. But it turned out I was elected, and I took up the position formally on April 27th. I am proud to have been elected as president and I will do my best to serve the EPS and respect the confidence that representatives of so many European national societies have put in me.

What do you hope to achieve during your two-year mandate?

I have several goals as president. The most important one is to strengthen the position of Europe. What do I mean by that? There are important issues that we all face together, such as our economic independence (for instance, sources of energy, technological advances in electronics, biophysics and medical applications) and the preservation of the environment. The EPS can play a role by building teams of experts to address these issues, to be in a position to advise policy makers at the European level.

Scientific policy is another example. We live in an era with very large changes in the scale of experiments, the size of datasets, as well as advanced data-analysis techniques such as artificial intelligence. We should be able to have a say about how these things are dealt with and what the priorities are. The EPS can have a solid dialogue with large experimental teams and important research centres such as CERN. We can pass the message, for example via the national physics societies, and provide lists of experts able to advise politicians on such matters.

Last but not least is education. We need to adapt the programmes offered to the students because there is huge demand for soft skills, and I am not sure they are adequately provided. We also need to offer opportunities to welcome students and early-career researchers from regions around the world that need support. We should collaborate with them and provide scholarships to enable them to spend time at a facility such as CERN or DESY and develop key skills.

To achieve all that, we should strengthen the links between the EPS and the national societies (be they small or large). We represent the interest of all physicists in Europe equally. We also need to have a more active dialogue with our colleagues in North America and Asia because we share common challenges. Of course, to do that requires hard work and commitment.

How can the EPS support fundamental research such as particle physics?

We have a high-energy physics division, of course. From my point of view, we need to accentuate the motivation for exploring the laws of the universe. CERN obviously plays a key role in this because colliders are one of the basic experimental devices to do so. Gravitational-wave observatories are another example. These experiments have to go hand-in-hand because they have a common ambition. The EPS can give an extra voice to the scientific aspects of this enterprise. Of course, the question of financing next-generation experiments remains to be solved, as well as the balance between fundamental science and applied research. For me there is no doubt that such experiments should continue. Unfortunately, today one often has to state the implications for industry and the applications for society. This can sometimes be difficult to square with curiosity-driven science.

If approved, would a new collider at CERN take away funding from other fields?

This is a very simplistic view. Science funding is not a zero-sum game. As CERN did for the LHC, it’s good to find external sources. Money can’t go to everyone in equal amounts, so we need a way to set scientific priorities in Europe. First and foremost, this should take into account the scientific case. Then we should look at the number of countries that are interested and the level of investments that have been made – for example, also involving industry.

Money can’t go to everyone in equal amounts, so we need a way to set scientific priorities in Europe

Is the scientific case for the Future Circular Collider sufficiently clear in this respect?

If the argument is to find super-symmetry, or particles predicted by some other framework of physics beyond the Standard Model, then I’m afraid it will fail. Of course, in scientific working groups you need to go into specifics such as which hypotheses will be tested, and which signatures are possible. But such detail is a trap when engaging with broader audiences because we can’t be sure that such things exist at the energies we can explore. Instead, the argument should be that we try to understand better the elementary particles and laws. We need to pass the message to politicians, to the person on the street and to scientists that there are some important questions that can only be addressed with future colliders. While CERN and particle physicists should not be defensive, they should be clearer about what the role and ultimate hope of a collider is. Then there is no argument that can go against it. This is something that could be elaborated by the high-energy physics division of the EPS, for example by providing a document stating the views of particle physicists. We should also be prepared for a critical dialogue, to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the arguments. One should in any case ensure that anyone invited to give their views should have an established scientific reputation within their field, a prerequisite that is not met in some high-level discussions and media outlets.

Does the existence of several future-collider options pose a problem from a communications perspective?

I think it’s problematic if, scientifically, a consensus cannot be reached. There is something similar going on in the gravitational-wave community, where divisions exist about where to build the Einstein Telescope and which configuration it should have. This may lead to a healthy process of course, but discussions should be kept between experts. Indeed, it can weaken the case for a new experiment if scientists are seen to be disagreeing strongly.

What effects are current political shifts in Europe having on physics?

I’m afraid that there could be very negative effects. To this we have to add the risks created by the conflicts we see expanding. One effect could also be the changes in priorities for funding. As one of the largest scientific societies, we need to keep supporting collaborations among scientists no matter their country of origin, ethnicity, gender, or any other discriminating factor. We also need to provide financial support where possible, for example as we have done recently for Ukrainian colleagues to participate in our activities, and to make statements in response to events going way beyond the world of physics.