On the night of 12 March, the Keck interferometer in Hawaii began operations. It is currently the largest optical

telescope in the world, with a resolution equivalent to that of a single telescope with a diameter of 85 m. Just five

days later, interferometry began at the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile.

The test was carried out with small 40 cm telescopes, but, when full-scale observations begin later in the year, the

facility will give a resolution equivalent to that of a 200 m telescope.

Interferometry – combining data from

several different telescopes to simulate the effect of using one large telescope – was originally the preserve of

radioastronomers. At longer wavelengths, the level of precision required to combine signals from the different

telescopes is easier to obtain. Thanks to interferometry, milliarcsecond resolution has been commonplace in

radioastronomy for many years.

Owing to great technological advances, optical interferometry is finally

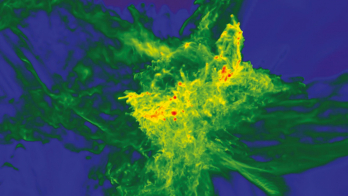

catching up, opening the door to a wealth of new discoveries. In particular, astronomers can now look forward to

the direct imaging of planets in other solar systems; seeing views of the surfaces of stars other than our Sun;

studying the environment close to black holes; and looking back in time to the epoch when the first stars and

galaxies started to shine.

However, although interferometry increases the resolution of observations,

sensitivity is much lower than that of a single large telescope. The mirrors do not collect as much light, so faint

objects are difficult to image. The Keck interferometer consists of two 10 m telescopes made up of 1.8 m mirror

segments. Meanwhile, the VLT has four 8.2 m telescopes and several 1.8 m auxiliary telescopes under

construction. This larger collecting area will give increased sensitivity.

The future is exciting, and CERN

Courier readers can look forward to some stunning “Pictures of the month” in years to come.