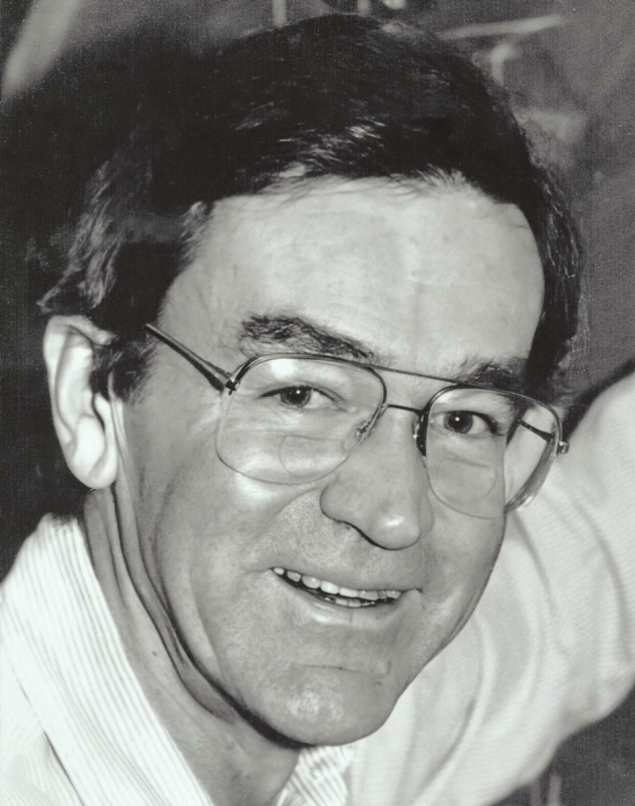

Theoretical physicist James D “BJ” Bjorken, whose work played a key role in revealing the existence of quarks, passed away on 6 August aged 90. Part of a wave of young physicists who came to Stanford in the mid-1950s, Bjorken also made important contributions to the design of experiments and the efficient operation of accelerators.

Born in Chicago on 22 June 1934, James Daniel Bjorken grew up in Park Ridge, Illinois, where he was drawn to mathematics and chemistry. His father, who had immigrated from Sweden in 1923, was an electrical engineer who repaired industrial motors and generators. After earning a bachelor’s degree at MIT, he went to Stanford University as a graduate student in 1956. He was one of half a dozen MIT physicists, including his adviser Sidney Drell and future director of the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory Burton Richter, who were drawn by new facilities on the Stanford campus. This included an early linear accelerator that scattered electrons off targets to explore the nature of the neutron and proton.

Ten years later those experiments moved to SLAC, where the newly constructed Stanford Linear Collider would boost electrons to much higher energies. By that time, theorists had proposed that protons and neutrons contained fundamental particles. But no one knew much about their properties or how to go about proving they were there. Bjorken, who joined the Stanford faculty in 1961, wrote an influential 1969 paper in which he suggested that electrons were bouncing off point-like particles within the proton, a process known as deep inelastic scattering. He started lobbying experimentalists to test it with the SLAC accelerator.

Carrying out the experiments would require a new mathematical language and Bjorken contributed to its development, with simplifications and improvements from two of his students (John Kogut and Davison Soper) and Caltech physicist Richard Feynman. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, those experiments confirmed that the proton does indeed consist of fundamental particles – a discovery honoured with the 1990 Nobel Prize in Physics for SLAC’s Richard Taylor and MIT’s Henry Kendall and Jerome Friedman. Bjorken’s role was later recognised by the prestigious Wolf Prize in Physics and the 2015 High Energy and Particle Physics Prize of the European Physical Society.

While the invention of “Bjorken scaling” was his most famous scientific achievement, Bjorken was also known for identifying a wide variety of interesting problems and tackling them in novel ways. He was somewhat iconoclastic. He also had colourful and often distinctly visual ways of thinking about physics – for instance, describing physics concepts in terms of plumbing or a baked Alaska. He never sought recognition for himself and was very generous in recognising the contributions of others.

In 1979 Bjorken headed east to become associate director for physics at Fermilab. He returned to SLAC in 1989, where he continued to innovate. Over the course of his career, among other things, he invented ideas related to the existence of the charm quark and the circulation of protons in a storage ring. He helped popularise the unitarity triangle and, along with Drell, co-wrote the widely used graduate-level textbooks Relativistic Quantum Mechanics and Relativistic Quantum Fields. In 2009 Bjorken contributed to an influential paper by three younger theorists suggesting approaches for searching for “dark” photons, hypothetical carriers of a new fundamental force.

He was also awarded the American Physical Society’s Dannie Heineman Prize, the Department of Energy’s Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award, and the Dirac Medal from the International Center for Theoretical Physics. In 2017 he shared the Robert R Wilson Prize for Achievement in the Physics of Particle Accelerators for groundbreaking theoretical work he did at Fermilab that helped to sharpen the focus of particle beams in many types of accelerators.

Known for his warmth, generosity and collaborative spirit, Bjorken passionately pursued many interests outside physics, from mountain climbing, skiing, cycling and windsurfing to listening to classical music. He divided his time between homes in Woodside, California and Driggs, Idaho, and thought nothing of driving long distances to see an opera in Chicago or dropping in unannounced at the office of some fellow physicist for deep conversations about general relativity, dark matter or dark energy – once remarking: “I’ve found the most efficient way to test ideas and get hard criticism is one-on-one conversation with people who know more than I do.”