As the LHC surpasses one exabyte of stored data – the largest scientific data set ever accumulated – Cristinel Diaconu and Ulrich Schwickerath call for new collaborations to join a global effort in data preservation, to allow future generations to unearth the hidden treasures.

In 2009, the JADE experiment had been inoperational for 23 years. The PETRA electron–positron collider that served it had already completed a second life as a pre-accelerator for the HERA electron–proton collider and was preparing for a third life as an X-ray source. JADE and the other PETRA experiments were a piece of physics history, well known for seminal measurements of three-jet quark–quark-gluon events, and early studies of quark fragmentation and jet hadronisation. But two decades after being decommissioned, the JADE collaboration was yet to publish one of its signature measurements.

At high energies and short distances, the strong force becomes weaker. Quarks behave almost like free particles. This “asymptotic freedom” is a unique hallmark of QCD. In 2009, as now, JADE’s electron–positron data was unique in the low-energy range, with other data sets lost to history. When reprocessed with modern next-to-next-to-leading-order QCD and improved simulation tools, the DESY experiment was able to rival experiments at CERN’s higher-energy Large Electron–Positron (LEP) collider for precision on the strong coupling constant, contributing to a stunning proof of QCD’s most fundamental behaviour. The key was a farsighted and original initiative by Siggi Bethke to preserve JADE’s data and analysis software.

New perspectives

This data resurrection from JADE demonstrated how data can be reinterpreted to give new perspectives decades after an experiment ends. It was a timely demonstration. In 2009, HERA and SLAC’s PEP-II electron–positron collider had been recently decommissioned, and Fermilab’s Tevatron proton–antiproton collider was approaching the end of its operations. Each facility nevertheless had a strong analysis programme ahead, and CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) was preparing for its first collisions. How could all this data be preserved?

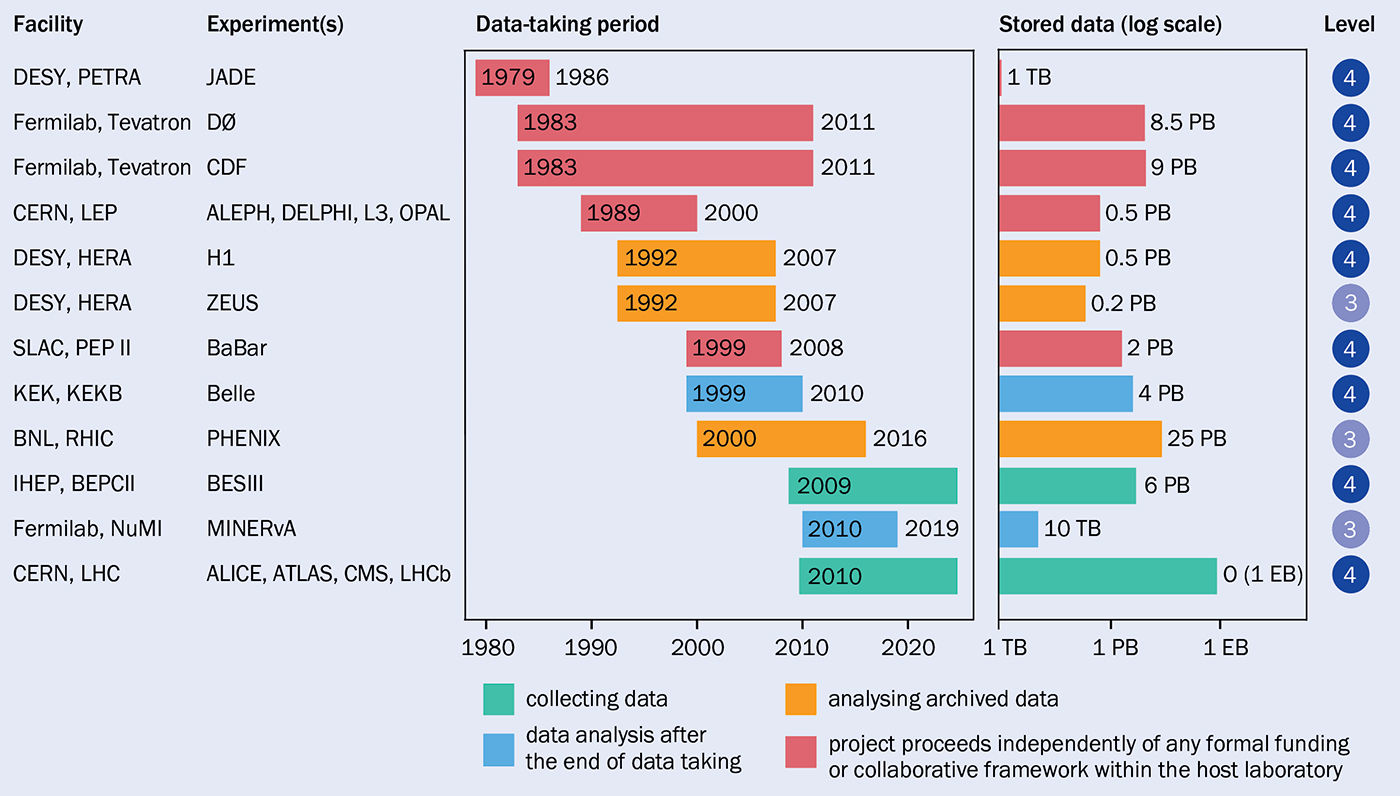

The uniqueness of these programmes, for which no upgrade or followup was planned for the coming decades, invited the consideration of data usability at horizons well beyond a few years. A few host labs risked a small investment, with dedicated data-preservation projects beginning, for example, at SLAC, DESY, Fermlilab, IHEP and CERN (see “Data preservation” dashboard). To exchange data-preservation concepts, methodologies and policies, and to ensure the long-term preservation of HEP data, the Data Preservation in High Energy Physics (DPHEP) group was created in 2014. DPHEP is a global initiative under the supervision of the International Committee for Future Accelerators (ICFA), with strong support from CERN from the beginning. It actively welcomes new collaborators and new partner experiments, to ensure a vibrant and long-term future for the precious data sets being collected at present and future colliders.

At the beginning of our efforts, DPHEP designed a four-level classification of data abstraction. Level 1 corresponds to the information typically found in a scientific publication or its associated HEPData entry (a public repository for high-energy physics data tables). Level 4 includes all inputs necessary to fully reprocess the original data and simulate the experiment from scratch.

At the beginning of our efforts, DPHEP designed a four-level classification of data abstraction. Level 1 corresponds to the information typically found in a scientific publication or its associated HEPData entry (a public repository for high-energy physics data tables). Level 4 includes all inputs necessary to fully reprocess the original data and simulate the experiment from scratch.

The concept of data preservation had to be extended too. Simply storing data and freezing software is bound to fail as operating systems evolve and analysis knowledge disappears. A sensible preservation process must begin early on, while the experiments are still active, and take into account the research goals and available resources. Long-term collaboration organisation plays a crucial role, as data cannot be preserved without stable resources. Software must adapt to rapidly changing computing infrastructure to ensure that the data remains accessible in the long term.

Return on investment

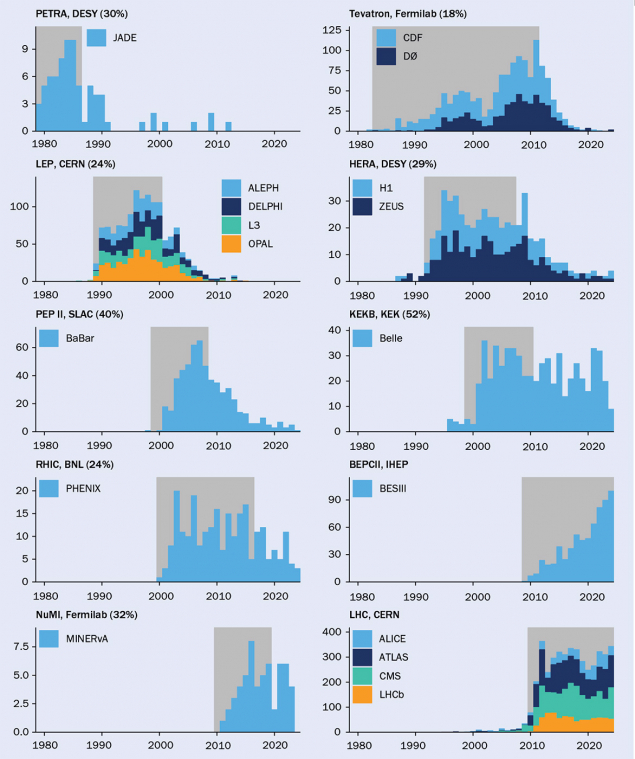

But how much research gain could be expected for a reasonable investment in data preservation? We conservatively estimate that for dedicated investments below 1% of the cost of the construction of a facility, the scientific output increases by 10% or more. Publication records confirm that scientific outputs at major experimental facilities continue long after the end of operations (see “Publications per year, during and after data taking” panel). Publication rates remain substantial well beyond the “canonical” five years after the end of the data taking, particularly for experiments that pursued dedicated data-preservation programmes. For some experiments, the lifetime of the preservation system is by now comparable with the data-taking period, illustrating the need to carefully define collaborations for the long term.

Publication records confirm that scientific outputs at major experimental facilities continue long after the end of operations

The most striking example is BaBar, an electron–positron-collider experiment at SLAC that was designed to investigate the violation of charge-parity symmetry in the decays of B mesons, and which continues to publish using a preservation system now hosted outside the original experiment site. Aging infrastructure is now presenting challenges, raising questions about the very-long-term hosting of historical experiments – “preservation 2.0” – or the definitive end of the programme. The other historical b-factory, Belle, benefits from a follow-up experiment on site.

Publications per year, during and after data taking

The publication record at experiments associated with the DPHEP initiative. Data-taking periods of the relevant facilities are shaded, and the fraction of peer-reviewed articles published afterwards is indicated as a percentage for facilities that are not still operational. The data, which exclude conference proceedings, were extracted from Inspire-HEP on 31 July 2025.

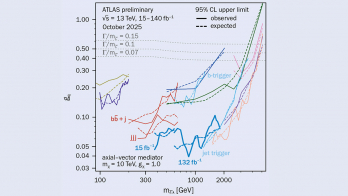

HERA, an electron– and positron–proton collider that was designed to study deep inelastic scattering (DIS) and the structure of the proton, continues to publish and even to attract new collaborators as the community prepares for the Electron Ion Collider (EIC) at BNL, nicely demonstrating the relevance of data preservation for future programmes. The EIC will continue studies of DIS in the regime of gluon saturation (CERN Courier January/February 2025 p31), with polarised beams exploring nucleon spin and a range of nuclear targets. The use of new machine-learning algorithms on the preserved HERA data has even allowed aspects of the EIC physics case to be explored: an example of those “treasures” not foreseen at the end of collisions.

IHEP in China conducts a vigorous data-preservation programme around BESIII data from electron–positron collisions in the BEPCII charm factory. The collaboration is considering using artificial intelligence to rank data priorities and user support for data reuse.

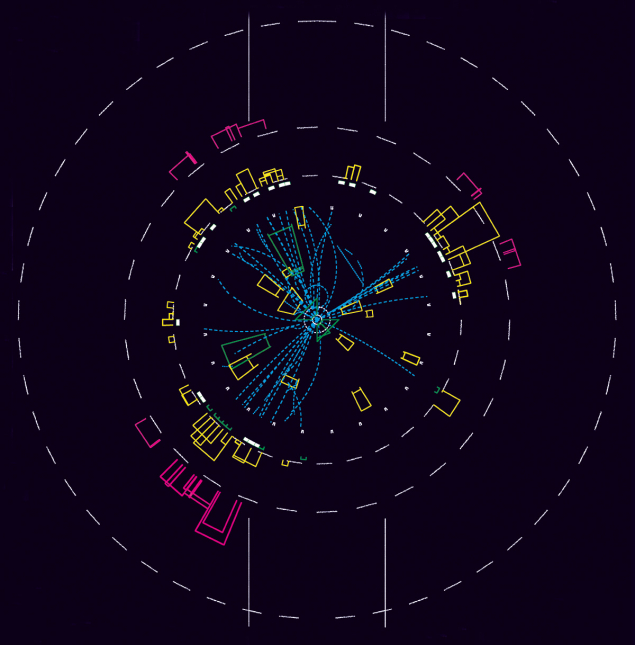

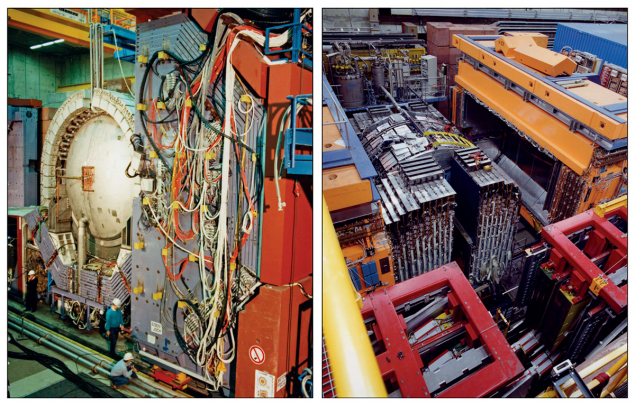

Remarkably, LEP experiments are still publishing physics analyses with archived ALEPH data almost 25 years after the completion of the LEP programme on 4 November 2000. The revival of the CERNLIB collection of FORTRAN data-analysis software libraries has also enabled the resurrection of the legacy software stacks of both DELPHI and OPAL, including the spectacular revival of their event displays (see “Data resurrection” figure). The DELPHI collaboration revised their fairly restrictive data-access policy in early 2024, opening and publishing their data via CERN’s Open Data Portal.

Some LEP data is currently being migrated into the standardised EDM4hep (event data model) format that has been developed for future colliders. As well as testing the format with real data, this will ensure data preservation and support software development, analysis training and detector design for the electron–positron collider phase of the proposed Future Circular Collider using real events.

The future is open

In the past 10 years, data preservation has grown in prominence in parallel with open science, which promotes free public access to publications, data and software in community-driven repositories, and according to the FAIR principles of findability, accessibility, interoperability and reusability. Together, data preservation and open science help maximise the benefits of fundamental research. Collaborations can fully exploit their data and share its unique benefits with the international community.

The two concepts are distinct but tightly linked. Data preservation focuses on maintaining data integrity and usability over time, whereas open data emphasises accessibility and sharing. They have in common the need for careful and resource-loaded planning, with a crucial role played by the host laboratory.

Data preservation and open science both require clear policies and a proactive approach. Beginning at the very start of an experiment is essential. Clear guidelines on copyright, resource allocation for long-term storage, access strategies and maintenance must be established to address the challenges of data longevity. Last but not least, it is crucially important to design collaborations to ensure smooth international cooperation long after data taking has finished. By addressing these aspects, collaborations can create robust frameworks for preserving, managing and sharing scientific data effectively over the long term.

Today, most collaborations target the highest standards of data preservation (level 4). Open-source software should be prioritised, because the uncontrolled obsolescence of commercial software endangers the entire data-preservation model. It is crucial to maintain all of the data and the software stack, which requires continuous effort to adapt older versions to evolving computing environments. This applies to both software and hardware infrastructures. Synergies between old and new experiments can provide valuable solutions, as demonstrated by HERA and EIC, Belle and Belle II, and the Antares and KM3NeT neutrino telescopes.

From afterthought to forethought

In the past decade, data preservation has evolved from simply an afterthought as experiments wrapped up operations into a necessary specification for HEP experiments. Data preservation is now recognised as a source of cost-effective research. Progress has been rapid, but its implementation remains fragile and needs to be protected and planned.

In the past 10 years, data preservation has grown in prominence in parallel with open science

The benefits will be significant. Signals not imagined during the experiments’ lifetime can be searched for. Data can be reanalysed in light of advances in theory and observations from other realms of fundamental science. Education, training and outreach can be brought to life by demonstrating classic measurements with real data. And scientific integrity is fully realised when results are fully reproducible.

The LHC, having surpassed an exabyte of data, now holds the largest scientific data set ever accumulated. The High-Luminosity LHC will increase this by an order of magnitude. When the programme comes to an end, it will likely be the last data at the energy frontier for decades. History suggests that 10% of the LHC’s scientific programme will not yet have been published when collisions end, and a further 10% not even imagined. While the community discusses its strategy for future colliders, it must therefore also bear in mind data preservation. It is the key to unearthing hidden treasures in the data of the past, present and future.

Further reading

DPHEP Collab. 2012 arXiv:1205.4667.

LHC Reinterpretation Forum 2025 arXiv:2504.00256.

DPHEP Collab. 2023 Eur. Phys. J. C 83 795.

CERN Open Data Portal: opendata.cern.ch.