Millions of asteroids orbit the Sun. Smaller fragments often brush the Earth’s atmosphere to light up the sky as meteors. Once every few centuries, a meteoroid has sufficient size to cause regional damage, most recently the Chelyabinsk explosion that injured thousands of people in 2013, and the Tunguska event that flattened thousands of square kilometres of Siberian forest in 1908. Asteroid impacts with global consequences are vastly rarer, especially compared to the frequency with which they appear in the movies. But popular portrayals do carry a grain of truth: in case of an impending collision with Earth, nuclear deflection would be a last-resort option, with fragmentation posing the principal risk. The most important uncertainty in such a mission would be the materials properties of the asteroid – a question recently studied at CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS), where experiments revealed that some asteroid materials may be stronger under extreme energy deposition than current models assume.

Planetary defence

“Planetary defence represents a scientific challenge,” says Karl-Georg Schlesinger, co-founder of OuSoCo, a start-up developing advanced material-response models used to benchmark large-scale nuclear deflection simulations. “The world must be able to execute a nuclear deflection mission with high confidence, yet cannot conduct a real-world test in advance. This places extraordinary demands on material and physics data.”

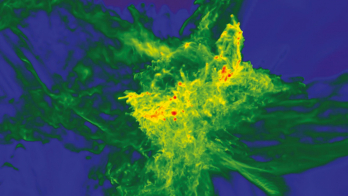

Accelerator facilities play a key role in understanding how asteroid material behaves under extreme conditions, providing controlled environments where impact-relevant pressures and shock conditions can be reproduced. To probe the material response directly, the team conducted experiments at CERN’s HiRadMat facility in 2024 and 2025, as a part of the Fireball collaboration with the University of Oxford. A sample of the Campo del Cielo meteorite, a metal-rich iron-nickel body, was exposed to 27 successive short, intense pulses of the 440 GeV SPS proton beam, reproducing impact-relevant shock conditions that cannot be achieved with conventional laboratory techniques.

“The material became stronger, exhibiting an increase in yield strength, and displayed a self-stabilising damping behaviour,” explains Melanie Bochmann, co-founder and co-team lead alongside Schlesinger. “Our experiments indicate that – at least for metal-rich asteroid material – a larger device than previously thought can be used without catastrophically breaking the asteroid. This keeps open an emergency option for situations involving very large objects or very short warning times, where non-nuclear methods are insufficient and where current models might assume fragmentation would limit the usable device size.”

Throughout the experiments at the SPS, the team monitored each pulse using laser Doppler vibrometry alongside temperature sensors, capturing in real time how the meteorite softened, flexed and then unexpectedly re-strengthened without breaking. This represents the first experimental evidence that metal-rich asteroid material may behave far more robustly under extreme, sudden energy loading than predicted.

The experiments could also provide valuable insights into planetary formation processes

After the SPS campaign, initial post-irradiation measurements were performed at CERN. These revealed that magnesium inclusions had been activated to produce sodium-22, a radioactive isotope that decays to produce a positron, allowing diagnostics similar to those used in medical imaging. Following these initial measurements, the irradiated meteorite has been transferred to the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the UK, where neutron diffraction and positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy measurements are planned.

“These analyses are intended to examine changes in the meteorite’s internal structure caused by the irradiation and to confirm, at a microscopic level, the increase in material strength by a factor of 2.5 indicated by the experimental results,” explains Bochmann.

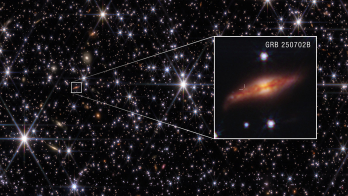

Complementary information can be gathered by space missions. Since NASA’s NEAR Shoemaker spacecraft successfully landed on asteroid Eros in 2001, two Japanese missions and a further US mission have visited asteroids, collecting samples and providing evidence that some asteroids are loosely bound rocky aggregates. In the next mission, NASA and ESA plan to study Apophis, an asteroid several hundreds of metres in size in each dimension that will safely pass closer to Earth than many satellites in geosynchronous orbit on 13 April 2029 – a close encounter expected only once every few thousand years.

The missions will observe how Apophis is twisted, stretched and squeezed by Earth’s gravity, providing a rare opportunity to observe asteroid-scale material response under natural tidal stresses. Bochmann and Schlesinger’s team now plan to study asteroids with a similar rocky composition.

Real-time data

“In our first experimental campaign, we focused on a metal-rich asteroid material because its more homogeneous structure is easier to control and model, and it met all the safety requirements of the experimental facility,” they explain. “This allowed us to collect, for the first time, non-destructive, real-time data on how such material responds to high-energy deposition.”

“As a next step, we plan to study more complex and rocky asteroid materials. One example is a class of meteorites called pallasites, which consist of a metal matrix similar to the meteorite material we have already studied, with up to centimetre-sized magnesium-rich crystals embedded inside. Because these objects are thought to originate from the core–mantle boundary of early planetesimals, such experiments could also provide valuable insights into planetary formation processes.”

Further reading

M Bochmann et al. 2025 Nat. Commun. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-66912-4.