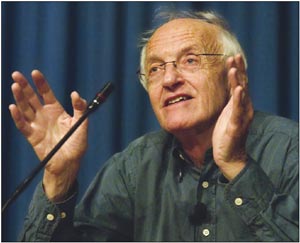

Carolyn Lee talks to the author and playwright about his life and his latest book.

When acclaimed playwright, novelist and translator Michael Frayn visited CERN in March there was a distinct air of humility about him. This Tony award winner, who is best known for such plays as Copenhagen and Noises Off, is genuinely honest and enthusiastic about science – a subject he openly claims he knows little about.

Frayn studied philosophy at Cambridge and went on to study in Russia during the Cold War, eventually becoming one of the leading translators of Russian literature. So, how did he find himself exploring science in his works? It all started in a rather serendipitous way: “When I was six years old there was a gang at school led by a fierce, Amazon-like girl, and because I wore spectacles I was appointed ‘gang scientist’. My job was to make explosives for the gang, using chalky soil, sawdust and elderberries.” Although he failed in his mission, this sparked his interest in science.

During his twenties Frayn served in the army and made friends with a fellow soldier who was fascinated by science and went on to become a zoologist. It was this friendship that introduced him to quantum theory and the uncertainty principle. As a student of philosophy, he also encountered extraordinary applications for these ideas, but it was not until the 1990s when he wrote Copenhagen that he began exploring science on a deeper level. “My only access to science is through the wonderful books that some scientists and science writers produce for the benefit of the lay people. Science becomes a very specialized subject and any non-scientist who ventures into it is a fool. But at the same time, I think you have to be an even bigger fool not to try to understand something, because it’s so important.”

Frayn indicates that modern, experimental science is possibly the greatest human achievement, affecting everything about the world and our general philosophical understanding of it. However, as Richard Feynman pointed out, to truly understand science, especially physics, one needs to understand mathematics. Despite this struggle to understand, Frayn says that it is important to let a little science into one’s life.

After bursting onto the scientific scene with his play Copenhagen, to much critical acclaim, Frayn was greatly struck by the generosity with which scientists treated it. He points out that there were a great many mistakes in the play, despite all of his efforts, and was surprised by the graciousness of the letters suggesting that he take another look at certain aspects. Whereas, “People in the arts, I think, take a great malicious pleasure in correcting each other,” he says.

Frayn first heard of Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg while on the services’ Russian course at Cambridge with his friend. Yet, he was only introduced to the story of Heisenberg’s visit to Bohr in Copenhagen in 1941 when he read a book by Thomas Powers called Heisenberg’s War. It was an unusual situation with old friends meeting under tremendously difficult circumstances as the Nazi regime had occupied the city. Many questions remain about the discussions that took place during this tense visit and the idea of such uncertainty sparked Frayn’s imagination.

“What fascinated me about the story are the questions it raises: Why did Heisenberg go to Copenhagen? What were his motives? And you can never really know the answer.” There is an uncertainty with human motivation and an uncertainty with the behaviour of a particle, and though the reasons are completely different, Frayn indicates that both have a theoretical barrier beyond which the human mind cannot reach, although he does encourage debate on this issue.

As for the scientists that he admires, he says: “All of them! I think Ernest Rutherford was a very interesting figure, and Niels Bohr because he was just a wonderful person. Science writer Richard Dawkins writes so well and tries to reach out to the lay readers, he truly appreciates the beauty of science.” He is also sympathetic to Werner Heisenberg, who he feels was put in a difficult position.

Touching the universe

Covering a wide range of disciplines, including linguistics, literature, neuroscience, philosophy and quantum physics, Frayn’s latest book, The Human Touch, asks whether the world has meaning or order other than what we give to it. The book also explores the similarities between science and fiction, both of which deal with narrative. He suggests that even the most abstract science is trying to tell a story and keep the interest of its audience. The Human Touch questions our place in the universe, a recurring theme in Frayn’s works. “The plays I’ve written are about how we organize the world around us, how we try to make sense out of it and try to make sense out of each other. I have been writing The Human Touch on and off for the past 30 years and I’ve tried to confront some of these questions.”

During his visit to CERN, Frayn gave a colloquium on his new book to CERN staff. Although a bit intimidated by the level of knowledge at CERN, he seemed to enjoy the opportunity to listen and debate with physicists about some of these philosophical questions.

After touring the ATLAS and CMS experiments, Frayn was stunned by CERN’s huge efforts to understand the universe more precisely. “I had no real concept of the sheer scale, the amount of effort and political skill needed, and the extraordinary technological complexity of it all, quite apart from the theories it will be testing. It really is quite amazing.” The desire to know our world better is something this philosophical writer appreciates, especially considering that these experiments are being constructed and performed in the sole interest of science, and not for monetary gain or military power.