Harold Shapiro reviews the work of the committee that he chaired to recommend priorities for US particle physics during the next 15 years.

I am not a particle physicist. I have spent most of my career as an economist and a university president with a sustained interest in science policy and its relationship to the health of the scientific enterprise and to long-term economic growth. But when the US National Research Council asked me to chair an independent committee of both physicists and non-physicists to look at the future role of the US programme in elementary-particle physics, I welcomed the chance to learn more about this intriguing area of science.

Some might wonder why such an unusual group of experts would be convened to provide advice to the US federal government on particle physics. Indeed, the committee that I chaired included members with expertise in particle physics, other branches of physics, engineering, scientific fields outside of physics, and even several non-scientists. Members from the larger international community of particle physicists were included as well. In many respects the nature of the strategic issues facing the US programme in particle physics required both fresh perspectives from a broader context and penetrating analysis to provide a credible path forward. To be frank, one of the first questions facing the committee was simply, “Does particle physics, especially accelerator-based experiments, still matter?”

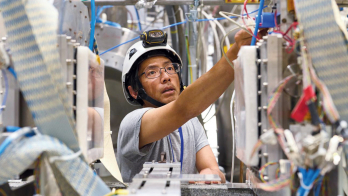

During its work, the committee engaged in a comprehensive set of data-gathering activities, including public meetings, letters to and from the global community, and numerous formal and informal discussions with stakeholders around the world. As part of our work, I travelled to the major particle-physics facilities in the US, Europe and Japan. In the US, most of the major facilities are scheduled to be shut down or converted to other uses within the next few years. Europe and Japan, in contrast, have recognized the scientific potential of particle physics and have been increasing their investments.

With respect to the US programme, what I found was a scientific field at a crossroads. Particle physicists could be on the verge of answering questions that human beings have asked for millennia. What are the origins of mass? Can the basic forces of nature be unified? How did the universe evolve? Why does it have the properties that it does? But even as the scientific opportunities have blossomed, our political and social will to sustain US commitment to this field has faltered. US leadership, together with that of our colleagues abroad, is important because it is critical to reaping the scientific, technological, economic and cultural dividends that come from advancing the scientific frontier.

As the field of particle physics took shape in the middle of the 20th century, America’s scientists focused on experiments designed to measure and explain the properties and forces governing the ultimate constituents of matter. Since then, even as the field became increasingly internationalized with distinguished centres abroad, the US has been home to some of the world’s most accomplished theorists, a diverse array of experiments, and some of the largest particle accelerators. Moreover the US has welcomed and greatly benefited from the intellectual and financial input of scientists from around the world. The US role in particle physics both anchored and symbolized the growing distinction and reach of the overall US scientific enterprise.

Before continuing, let me say something about the word “leadership,” especially with such an international audience where this term may carry nationalistic or even imperialistic overtones. In the context of current discussions about globalization, “the flat world” and the growing interdependence of national efforts around the world, what does leadership mean for the US in a field such as particle physics? Leadership does not mean dominance, but rather taking initiative at the frontiers, accepting appropriate risks, and catalysing partnerships both at home and abroad. Given the wide distribution of talent and facilities it is not only futile but an irresponsible use of public resources for any country or region to aspire to dominance. In the world that lies before us, leadership will be a shared phenomenon that flows from developing and brokering mutual gains among equal partners. In articulating a strategy for the US, the committee sought a path that leveraged US strengths for the benefit of not only the domestic programme, but also the global enterprise. In terms of scientific facilities, this means that we must move from a paradigm of “We’re going to build this, will you help us?” to one of “What can we build together that will benefit us all?”

The US is now on the verge of forfeiting its role among the international leaders in particle physics. Operations at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Europe will soon begin and it will become the world’s most powerful accelerator. Like many other fields in the physical sciences, federal funding for particle physics in the US has stagnated for more than a decade, and the field is gradually losing US researchers and students. Within a few years, the majority of US experimental particle physicists will be working on experiments that are being conducted in other countries. Simply put, the intellectual centre of gravity is moving abroad and the US has not put forward a compelling strategic vision to contribute to the global enterprise.

This potential retreat of the US programme in particle physics from the scientific frontiers could not be happening at a worse time. Particle physics is entering one of the most exciting periods in its history. The technologies needed to do experiments at the terascale are now available, and both theoretical and experimental results point towards revolutionary new discoveries that will be made at this scale. Physicists could not only discover new dimensions and the particles responsible for mass (or other phenomena unimagined today), but these experiments could also provide clues to the nature of dark energy and dark matter, which are essential to our comprehension of the universe. Indeed in the next few decades particle physics could yield a radical new view of the cosmos.

Even as the Europeans have been finishing the LHC, particle physicists worldwide have been designing the next generation of particle accelerator. Known as the International Linear Collider (ILC), this new tool would comprise two accelerators that fire electrons and anti-electrons at each other head-on, probing conditions that existed just a fraction of a second after the birth of the universe. The ILC is so important and so large an undertaking that it can only arise from a global effort. The potential role of the US in building, supporting, and perhaps hosting the ILC is now a key to the continued distinction of the US programme. Indeed, participation in the scientific opportunities addressed by the ILC is likely to be important for any nation actively engaged in particle physics, but it is particularly important now for the US because of the absence of any other key strategic focus.

To ensure its vitality in particle physics and to contribute effectively to the global effort, the US must be willing to do three things. First, it must maintain a broad range of theoretical and experimental programmes, since new discoveries often come from unexpected places. Second, it must make a commitment to participating in the direct and controlled exploration of the terascale. In part, that means supporting the work of US scientists at the LHC. It also means investing the risk capital so that the US can be in a position, four or five years from now, to mount a compelling bid to host the ILC – if the US decides then that it is still in its best interests to compete for the ILC. For the US to mount a compelling bid, however, it must not only demonstrate the technical capabilities and economic resources necessary for hosting the ILC, but it must also demonstrate the energy, enthusiasm and commitment that are required to be a credible international partner. Moreover, the science of the terascale is so compelling that the US should play a strong role in the ILC no matter where it is sited. Third, to ensure a responsible use of public funds, the US must make an increased commitment to establishing mutually advantageous joint ventures with its colleagues abroad.

Scientific leadership, like competitiveness, is won generation by generation, but once it is lost it is difficult for the next generation to win it back. Students stop enrolling in graduate programmes, university departments scale back or shut down, researchers emigrate, retire or move to other fields. Maintaining the leading role of the US will need continued federal support, probably at a greater level than at present if the US mounts a compelling bid and is chosen to host the ILC. But the history of science demonstrates that our investments can be expected to repay themselves many times over.