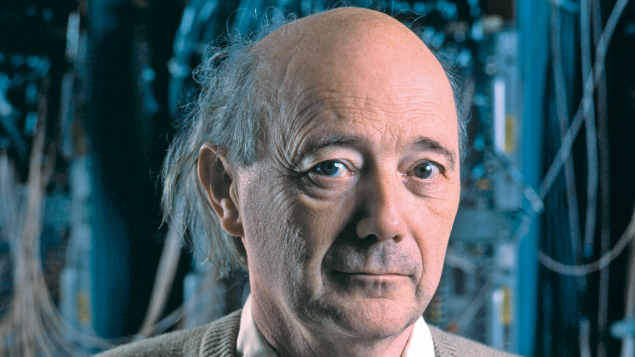

Ole Hansen, a leading Danish nuclear-reaction physicist, passed away on 11 May 2025, three days short of his 91st birthday. His studies of nucleon transfer between a projectile nucleus and a target nucleus made it possible to determine the bound states in either or both nuclei and confront it with the framework for which the Danish Nobel Prize winners Aage Bohr and Ben Mottelson had developed a unified theory. He conducted experiments at Los Alamos in the US and Aldermaston in the UK, among others, and developed a deep intuitive relationship with Clebsch–Gordan coefficients.

Together with Ove Nathan, Ole oversaw a proposal to build a large tandem accelerator at the Niels Bohr Institute department located at Risø, near Roskilde. The government and research authorities had supported the costly project, but it was scrapped on an afternoon in August 1978 as a last-minute saving to help establish a coalition between the two parties across the centre of Danish politics. Ole’s disappointment was enormous: he decided to take up an offer at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) to continue his nuclear work there, while Nathan threw himself into university politics and later became rector of the University of Copenhagen.

Deep exploration

Ole sent his resignation as a professor at the University of Copenhagen to the Queen – a civil servant had to do so at the time – but was almost immediately confronted with demands for cutbacks at BNL, which would stop the research programme with the tandem accelerator there. Ole did not withdraw his resignation, but together with US colleagues proposed a research programme at very high energies by injecting ions from the tandem into the existing particle accelerator, AGS, thereby achieving energies in the nucleon–nucleon centre-of-mass system of up to 5 GeV. This was the start of the exploration of the deeper structure of nuclear matter, which is revealed as a system consisting of quarks and gluons at temperatures of billions of degrees. This later led to the construction of the first atomic nucleus collision machine, the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) in the US. Ole himself participated in the E802 and E866 experiments at BNL/AGS, and in the BRAHMS experiment at RHIC.

Ole will be remembered as the first director of the unified Niels Bohr Institute and for establishing the Danish National Research Foundation

Ole will also be remembered as the first director, called back from the US, of the unified Niels Bohr Institute, which was established in 1993 as a fusion of the physics, astronomy and geophysics departments surrounding the Fælledparken commons in Copenhagen after an international panel chaired by him had recommended a merger. Ole realised the necessity of merging the departments in order to create the financial room for manoeuvre needed to be able to hire new and younger researchers again. He left his mark on the construction, which initially had to deal with the very different cultures of the Blegdamsvej, Ørsted and Geophysics institutes. He approached the task efficiently but with a good understanding and respect for the scientific perspectives and the individual researchers.

Back in Denmark, Ole played a significant role in the establishment of the competitive research system we know today, including the establishment of the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF), of which he was vice-chair in the first years, and with the streamlining of the institute’s research and the establishment of several new areas.

Strong interests

Despite the scale of all his administrative tasks, Ole maintained a lively interest in research and actively supported the establishment of the Centre for CERN Research (now the NICE National Instrument Center) together with the author of this obituary. He was also a member of the CERN Council during the exciting period when the LHC took shape.

Ole will be remembered as an open-minded, energetic and visionary man with an irreverent sense of humour that some feared but others greatly appreciated. Despite his modest manner, he influenced his colleagues with his strong interest in new physics and his sharp scepticism. If consulted, he would probably turn his nose up at the word “loyal”, but he was ever a good and loyal friend. He is survived by his wife, Ruth, and four children.