In lead collisions at the LHC, some of the strongest electromagnetic fields in the universe bombard the inside of the beam pipe with radioactive gold. By following the collision fragments, John Jowett explores a little-known link between nuclear physics and the performance limits of heavy-ion colliders.

New results in fundamental physics can be a long time coming. Experimental discoveries of elementary particles have often occurred only decades after their prediction by theory.

Still, the discovery of the fundamental particles of the Standard Model has been speedy in comparison to another longstanding quest in natural philosophy: chrysopoeia, the medieval alchemists’ dream of transforming the “base metal” lead into the precious metal gold. This may have been motivated by the observation that the dull grey, relatively abundant metal lead is of similar density to gold, which has been coveted for its beautiful colour and rarity for millennia.

The quest goes back at least to the mythical, or mystical, notion of the philosopher’s stone and Zosimos of Panopolis around 300 CE. Its evolution, in various cultures, through medieval times and up to the 19th century, is a fascinating thread in the emergence of modern empirical science from earlier ways of thinking. Some of the leaders of this transition, such as Isaac Newton, also practised alchemy. While the alchemists pioneered many of the techniques of modern chemistry, it was only much later that it became clear that lead and gold are distinct chemical elements and that chemical methods are powerless to transmute one into the other.

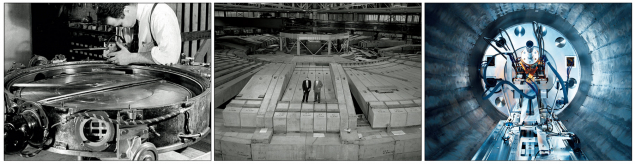

With the dawn of nuclear physics in the 20th century, it was discovered that elements could transform into others through nuclear reactions, either naturally by radioactive decay or in the laboratory. In 1940, gold was produced at the Harvard Cyclotron by bombarding a mercury target with fast neutrons. Some 40 years ago, tiny amounts of gold were produced in nuclear reactions between beams of carbon and neon, and a bismuth target at the Bevalac in Berkeley. Very recently, gold isotopes were produced at the ISOLDE facility at CERN by bombarding a uranium target with proton beams (see “Historic gold” images).

Now, tucked away discreetly in the conclusions of a paper recently published by the ALICE collaboration, one can find the observation, originating from Igor Pshenichnov, Uliana Dmitrieva and Chiara Oppedisano, that “the transmutation of lead into gold is the dream of medieval alchemists which comes true at the LHC.”

ALICE has finally measured the transmutation of lead into gold, not via the crucibles and alembics of the alchemists, nor even by the established techniques of nuclear bombardment used in the experiments mentioned above, but in a novel and interesting way that has become possible in “near-miss” interactions of lead nuclei at the LHC.

At the LHC, lead has been transformed into gold by light.

Since the first announcement, this story has attracted considerable attention in the media. Here I would like to put this assertion in scientific context and indicate its relevance in testing our understanding of processes that can limit the performance of the LHC and future colliders such as the FCC.

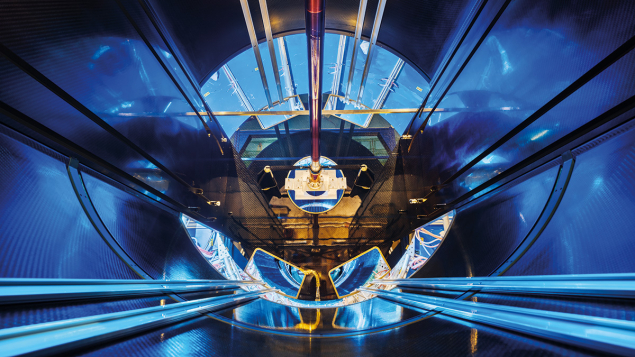

Electromagnetic pancakes

Any charged particle at rest is surrounded by lines of electric fields radiating outwards in all directions. These fields are particularly strong close to a lead nucleus because it contains 82 protons, each with one elementary charge. In the LHC, the lead nuclei travel at 99.999994% of the speed of light, squeezing the field lines into a thin pancake transverse to the direction of motion in the laboratory frame of reference. This compression is so strong that, in the vicinity of the nucleus, we find the strongest magnetic and electric fields known in the universe, trillions of times stronger than even the prodigiously powerful superconducting magnets of the LHC, and orders of magnitude greater than the Schwinger limit where the vacuum polarises or the magnetic fields found in rare, rapidly spinning neutron stars called magnetars. Of course, these fields extend only over a very short time as one nucleus passes by the other. Quantum mechanics, via a famous insight of Fermi, Weizsäcker and Williams, tells us that this electromagnetic flash is equivalent to a pulse of quasi-real photons whose intensity and energy are greatly boosted by the large charge and the relativistic compression.

When two beams of nuclei are brought into collision in the LHC, some hadronic interactions occur. In the unimaginable temperatures and densities of this ultimate crucible we create droplets of the quark–gluon plasma, the main subject of study of the heavy-ion programme. However, when nuclei “just miss” each other, the interactions of these electromagnetic fields amount to photon–photon and photon–nucleus collisions. Some of the processes occurring in these so-called ultra-peripheral collisions (UPCs) are so strong that they would limit the performance of the collider, were it not for special measures implemented in the last 10 years.

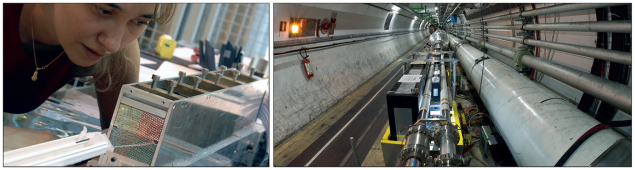

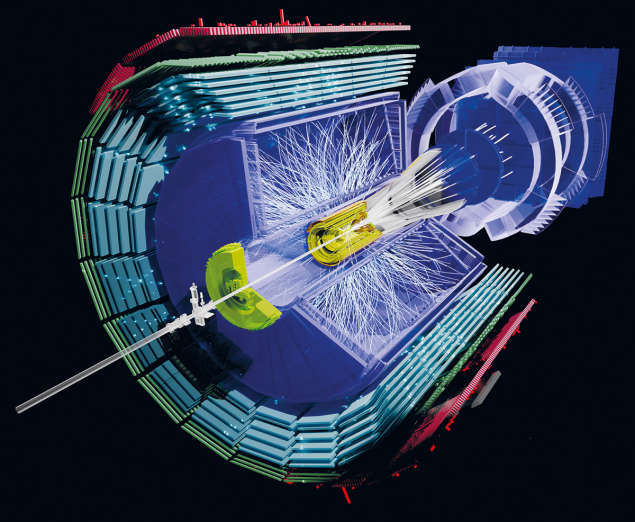

The ALICE paper is one among many exploring the rich field of fundamental physics studies opened up by UPCs at the LHC (CERN Courier January/February 2025 p31). Among them are electromagnetic dissociation processes where a photon interacting with a nucleus can excite oscillations of its internal structure and result in the ejection of small numbers of neutrons and protons that are detected by ALICE’s zero degree calorimeters (ZDCs). The ALICE experiment is unique in having calorimeters to detect spectator protons as well as neutrons (see “Spotting spectators” figure). The residual nuclei are not detected although they contribute to the signals measured by the beam-loss monitor system of the LHC.

Each 208Pb nucleus in the LHC beams contains 82 protons and 208–82 = 126 neutrons. To create gold, a nucleus with a charge of 79, three protons must be removed, together with a variable number of neutrons.

Alchemy in ALICE

While less frequent than the creation of the elements thallium (single-proton emission) or mercury (two-proton emission), the results of the ALICE paper show that each of the two colliding lead-ion beams contribute a cross section of 6.8 ± 2.2 barns to gold production, implying that the LHC now produces gold at a maximum rate of about 89 kHz from lead–lead collisions at the ALICE collision point, or 280 kHz from all the LHC experiments combined. During Run 2 of the LHC (2015–2018), about 86 billion gold nuclei were created at all four LHC experiments, but in terms of mass this was only a tiny 2.9 × 10–11 g of gold. Almost twice as much has already been produced in Run 3 (since 2023).

The transmutation of lead into gold is the dream of medieval alchemists which comes true at the LHC

Strikingly, this gold production is somewhat larger than the rate of hadronic nuclear collisions, which occur at about 50 kHz for a total cross section of 7.67 ± 0.25 barns.

Different isotopes of gold are created according to the number of neutrons that are emitted at the same time as the three protons. To create 197Au, the only stable isotope and the main component of natural gold, a further eight neutrons must be removed – a very unlikely process. Most of the gold produced is in the form of unstable isotopes with lifetimes of the order of a minute.

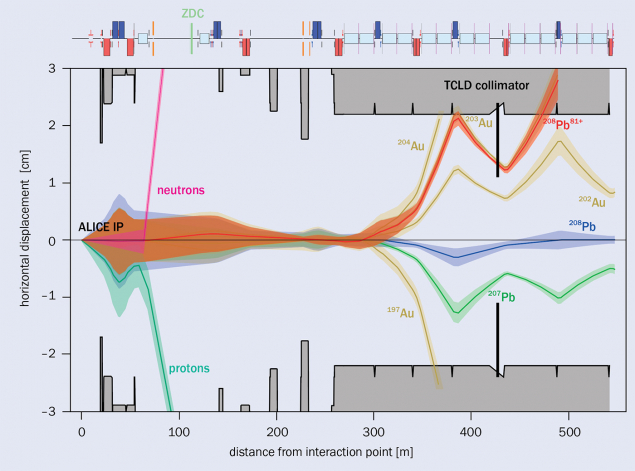

Although the ZDC signals confirm the proton and neutron emission, the transformed nuclei are not themselves detected by ALICE and their fate is not discussed in the paper. These interaction products nevertheless propagate hundreds of metres through the beampipe in several secondary beams whose trajectories can be calculated, as seen in the “Ultraperipheral products” figure.

The ordinate shows horizontal displacement from the central path of the outgoing beam. This coordinate system is commonly used in accelerator physics as it suppresses the bending of the central trajectory – downwards in the figure – and its separation into the beam pipes of the LHC arcs.

The “5σ” envelope of the intense main beam of 208Pb nuclei that did not collide is shown in blue. Neutrons from electromagnetic dissociation and other processes are plotted in magenta. They begin with a certain divergence and then travel down the LHC beam pipe in straight lines, forming a cone, until they are detected by the ALICE ZDC, some 114 m away from the collision, after the place where the beam pipe splits in two. Because of the coordinate system, the neutron cone appears to bend sharply at the first separation dipole magnet.

Protons are shown in green. As they only have 40% of the magnetic rigidity of the main beam, they bend quickly away from the central trajectory in the first separation magnet, before being detected by a different part of the ZDC on the other side of the beam pipe.

Photon–photon interactions in UPCs copiously produce electron–positron pairs. In a small fraction of them, corresponding nevertheless to a large cross-section of about 280 barns, the electron is created in a bound state of one of the 208Pb nuclei, generating a secondary beam of 208Pb81+ single-electron ions. The beam from this so-called bound-free pair production (BFPP), shown in red, carries a power of about 150 W – enough to quench the superconducting coils of the LHC magnets, causing them to transition from the superconducting to the normal resistive state. Such quenches can seriously disrupt accelerator operation, as the stored magnetic energy is rapidly released as heat within the affected magnet.

To prevent this, new “TCLD” collimators were installed on either side of ALICE during the second long shutdown of the LHC. Together with a variable-amplitude bump in the beam orbit, which pulls the BFPP beam away from the first impact point so that it can be safely absorbed on the TCLD, this allowed the luminosity to be increased to more than six times the original LHC design, just in time to exploit the full capacity of the upgraded ALICE detector in Run 3.

Light-ion collider

Besides lead, the LHC has recently collided beams of 16O and 20Ne (see “First oxygen and neon collisions at the LHC”), and nuclear transmutation has manifested itself in another way. In hadronic or electromagnetic events where equal numbers of protons and neutrons are emitted, the outgoing nucleus has almost the same charge-to-mass ratio, since nuclear binding energies are very small at the top of the periodic table. It may then continue to circulate with the original beam, resulting in a small contamination that increases during the several hours of an LHC fill. Hybrid collisions can then occur, for example including a 14N nucleus formed by the ejection of a proton and a neutron from 16O. Fortunately, the momentum spread introduced by the interactions puts many of these nuclei outside the acceptance of the radio-frequency cavities that keep the beams bunched as they circulate around the ring, so the effect is smaller than had first been expected.

The most powerful beam from an electromagnetic-dissociation process is 207Pb from single neutron emission, plotted in green. It has comparable intensity to 208Pb81+ but propagates through the LHC arc to the collimation system at Point 3.

Similar electromagnetic-dissociation processes occur elsewhere, notably in beam interactions with the LHC collimation system. The recent ALICE paper, together with earlier ones on neutron emissions in UPCs, helps to test our understanding of the nuclear interactions that are an essential ingredient of complex beam-physics simulations. These are used to understand and control beam losses that might otherwise provoke frequent magnet quenches or beam dumps. At the LHC, a deep symbiosis has emerged between the fundamental nuclear physics studied by the experiments and the accelerator physics limiting its performance as a heavy-ion collider – or even as a light-ion collider (see “Light-ion collider” panel).

The figure also shows beams of the three heaviest gold isotopes in gold. 204Au has an impact point in a dipole magnet but is far too weak to quench it. 203Au follows almost the same trajectory as the BFPP beam. 202Au propagates through the arc to Point 3. The extremely weak flux of 197Au, the only stable isotope of gold, is also shown.

Worth its weight in gold

Prospecting for gold at the LHC looks even more futile when we consider that the gold nuclei emerge from the collision point with very high energies. They hit the LHC beam pipe or collimators at various points downstream where they immediately fragment in hadronic showers of single protons, neutrons and other particles. The gold exists for tens of milliseconds at most.

And finally, the isotopically pure lead used in CERN’s ion source costs more by weight than gold, so realising the alchemists’ dream at the LHC was a poor business plan from the outset.

The moral of this story, perhaps, is that among modern-day natural philosophers, LHC physicists take issue with the designation of lead as a “base” metal. We find, on the contrary, that 208Pb, the heaviest stable isotope among all the elements, is worth far more than its weight in gold for the riches of the physics discoveries that it has led us to.

Further reading

R Sherr et al. 1941 Phys. Rev. 60 473.

K Aleklett et al. 1981 Phys. Rev. C 23 1044.

A E Barzakh et al. 2022 Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 513 26.

ALICE Collab. 2025 Phys. Rev. C 111 054906.

M Schaumann et al. 2020 Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 23 121003.