by John Campbell, AAS publications, 494pp hbk £25/$40 (obtainable direct from the publisher: AAS publications, PO Box 31-035, Christchurch, New Zealand; e-mail “aas@its.canterbury.ac.nz”).

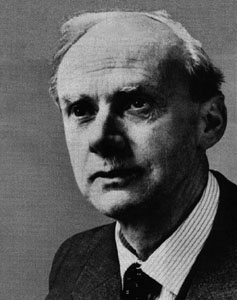

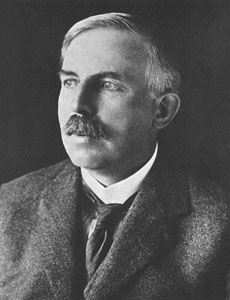

Ernest Rutherford towered over the early 20th-century decryption of the atom. At a series of university settings – Cambridge, McGill, Manchester and then Cambridge again – he masterminded a progression of classic experiments that dramatically revealed the nature of radioactivity, and the structure of the atom and its nucleus. Many of those he had chosen to be his research partners – Blackett, Chadwick, Cockcroft, Geiger and Walton, among others – went on to become physics figureheads in their own right. In Manchester, Rutherford inspired Niels Bohr to abandon the theory of electrons in metals and turn to that of electrons in atoms instead.

Rutherford biographies are not scarce, with inspired memoirs and nostalgic reminiscences by several contemporaries – Allibone, Da Costa Andrade, Oliphant – and the 1983 biography Rutherford, Simple Genius by David Wilson.

The title of Wilson’s book succinctly catches the nature of Rutherford. He was no fiery intellect like many of his central European contemporaries. Instead, his slow but penetrating insight and analysis, and his gift for patient, incisive investigation, isolated key problems and elucidated them.

Rutherford was born in modest surroundings in New Zealand when the country was still being settled. When New Zealand schoolchildren of the late 19th century learned history, they learned British history – there was no New Zealand history. University examination papers were despatched by boat to Britain for marking.

New Zealander John Campbell – he teaches physics at the University of Canterbury – was struck, ashamed even, by the lack of recognition of his nation’s premier scientist and he set out to do something about it. He developed a fitting memorial at Rutherford’s birthplace in Nelson and embarked on this major biography, which fleshed out Rutherford’s New Zealand background. While other epochs in Rutherford’s life have been well documented, his youthin New Zealand has until now been largely overlooked. Compared with 50 sketchy pages in Wilson’s book, perhaps half of Campbell’s book deals with local matters – Rutherford’s birth, schooling, early university education and periodic visits throughout his life. During his studies, Rutherford emerged as a gifted student but no precocious childhood genius.

As well as the focus on New Zealand, there is much valuable additional material in the book – anecdotes, the paradox of how the 20th century’s foremost experimental physicist never received the Nobel Prize for Physics (even before his historic discovery of the atomic nucleus in 1911, he received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his work on radioactivity), several major discoveries that were missed at Cambridge in the early 1930s – the positron, induced radioactivity – and finally the bizarre circumstances of his death at the age of only 66. (Details of Rutherford’s death are strangely absent in existing biographies, written when many people still had an upright Victorian attitude.) Rutherford had been influential in key applied research positions in the First World War. What impact would his blustering no-nonsense personality have made in Second World War science and technology?

The book underlines Rutherford’s continual push for higher-energy particles. In a 1927 speech to the Royal Society, he said: “It has long been my ambition to have available for study a copious supply of atoms and electrons which have an individual energy far transcending that of particles from radioactive bodies.” At Cambridge, industrial techniques were exploited in the search for higher voltages – an early example of technology transfer. This ultimately led to Cockcroft and Walton’s accelerator, carried further by Oliphant. However, Rutherford dropped the ball by not acknowledging the arrival of the upstart cyclotron, developed by Ernest Lawrence in the US.

Especially poignant is the description of Rutherford’s undemonstrative romance and marriage to the faithful Mary (“May”) Newton, whom he met while a student in New Zealand and who eventually followed him to Britain after patiently waiting to be summoned.

Campbell’s homely but complete biography of “Ern” is totally in keeping with Rutherford’s own bluntness – a valuable addition to the biography of a key scientific figure. It will be particularly appreciated in New Zealand, even if major world publishers did not agree with this antipodean focus. A shorter 250-page version is thus in the pipeline.