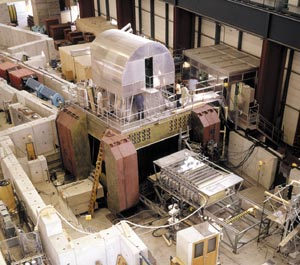

The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year. The anniversary conference, “Legacy for the Future”, took place on 4-5 October in the centre’s main building, which is adjacent to the Adriatic Sea about 10 km from Trieste in northeastern Italy. Some 300 scientists, many of whom are long-time associates and friends of ICTP, came to Trieste to celebrate the anniversary of an institution that is widely respected and revered. Among them were four Nobel laureates: Walter Kohn of the University of California at Santa Barbara; Rudolph A Marcus and Ahmed H Zewail of the California Institute of Technology; and John Nash, Jr, of Princeton University.

Exactly 40 years earlier, on 5 October 1964, a group of public officials, largely from Italy, joined eminent scientists from around the world at the Jolly Hotel in downtown Trieste for the inaugural meeting of the newly created ICTP. A seminar on plasma physics served as the scientific platform from which the centre was officially launched. Abdus Salam, who had led the effort for the creation of the centre, hosted the meeting. Marshall Rosenbluth, professor of physics at the University of California, San Diego, and a former student of Edward Teller, served as one of the main organizers. Sigvard Eklund, director-general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was there. So too were Guido Gerin, the Italian government’s representative to IAEA, and Begum Liaquat Ali Khan, Pakistan’s ambassador to Italy. In all, more than 70 scientists were in attendance, representing 14 countries in the West, five in the East and 12 from the South.

Four years later, on 7-29 June 1968, ICTP had organized a star-studded symposium on contemporary physics. The event took place not in downtown Trieste but in the centre’s then newly completed main building, not far from Miramare Castle Park, which was once the private estate of Maximilian, younger brother of the Hapsburg Emperor Franz Josef who had ruled the Austro-Hungarian empire from 1848 to 1916. The symposium, attended by nearly 300 scientists from some 40 countries, brought 21 current and future Nobel prize winners to Trieste. Eminent scientists in attendance included Hans Bethe, Francis Crick, Paul Dirac, Werner Heisenberg and Eugene Wigner.

During the four years leading up to the creation of the centre and the first four years of its existence, many of the principles and programmes that have guided ICTP ever since were put in place. The centre has evolved over the past 40 years, but that evolution has unfolded within the context of its long-standing mandate. Indeed the centre’s guiding principles have remained remarkably unchanged throughout its history. These include:

• Promoting and, where possible, providing world-class research facilities for scientists from the developing world.

• Conducting and fostering advanced scientific research at a high level, especially in theoretical physics and mathematics.

• Creating an international forum for the exchange of scientific information through courses, workshops and seminars in high-energy physics, condensed-matter physics, mathematics and a host of disciplines in which physics and mathematics play a critical role in analyses and research.

ICTP achieves its goals through a variety of programmes, many of which were established in the 1960s and have since become the “standard models” for efforts to build scientific capacity in developing nations. One of the most notable initiatives has been the Associateship Programme, which enables scientists from the developing world to visit ICTP for extended periods several times over a number of years (under the current rules each associate may visit three times for at least 40 days over a six-year period). The strategy is designed to enable scientists to keep abreast of developments within their fields without having to leave their home countries permanently. Over the past four decades nearly 2000 scientists from 77 developing nations have been appointed ICTP associates. Many have gone on to distinguished careers both as scientists and as science administrators.

Other ICTP programmes include the Federation Scheme, which enables institutions to regularly send members of their research staff to ICTP; the Office of External Activities, which sponsors a variety of research activities in developing countries; the Diploma Course Programme, which provides young students with a year’s training in Trieste, leading to a certificate that is equivalent to a master’s degree; and the Training and Research in Italian Laboratories Programme, which offers scientists in the developing world opportunities to work in scientific institutions in Italy. Over the past 40 years some 100 000 scientists from more than 170 countries have participated in ICTP’s schools, workshops and conferences or have come to the centre as visiting scientists with the opportunity to pursue their own research and forge new collaborations.

Today the centre sponsors more than 40 research and training activities annually that attract on average a total of 4000 scientists. Another 1000 come to ICTP each year to participate in activities that the centre hosts for other organizations, including local institutions and organizations both in Italy and around the world.

In today’s world, when it comes to economic and social well being, developing nations face the dual challenge of trying to catch up with developed countries while simultaneously keeping abreast of the latest technologies. While the statistics provide precise indicators of the centre’s success they fail to reveal how ICTP has been able to do what it does, the challenges that it has faced and its ability to adapt to changing circumstances. The centre’s early history and its struggles and triumphs during the 1960s and 1970s not only shed revealing light on ICTP, but also on how much science, particularly science in the developing world, has changed over the past four decades – and how much it hasn’t.

The centre’s roots lie post-World War Two, in an era marked by a conflicting sense of heady optimism and deep concern. On the one hand the end of the colonial era laid the groundwork for developing countries to seek independence and to pursue initiatives that would provide their citizens with the necessary skills that their nations would need to succeed on their own, including improved abilities in science and technology. On the other hand the rise of the Cold War, which in many respects reached its most heated moments during the 1960s, sparked tensions between East and West that continually threatened to erupt into global armed conflict between the world’s two superpowers, both of which had extensive nuclear arsenals. ICTP was a response to both of these global concerns.

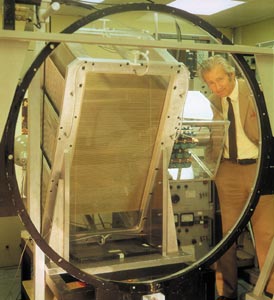

Abdus Salam, a Pakistani-born prodigy, who had earned a PhD from the University of Cambridge in the UK under a programme designed to assist gifted young scientists from developing countries in the Commonwealth, called for the creation of an institution that would allow developing-world scientists to avoid the dilemma he had faced as a young scientist in the 1950s: to remain in his native Pakistan and forego his career or to return to the UK to continue his research and teaching in an environment that would allow him to reach his full potential. As a member of the Pakistani delegation to the IAEA General Conference in 1960 in Vienna, Austria, he used his position to seek the agency’s support for his proposal to create an international physics centre that would provide training and research opportunities for scientists from the developing world. His goal was to enable scientists from the South to pursue their careers without having to leave their home countries.

At the same time Paolo Budinich, professor of physics at the University of Trieste and an Italian citizen born in what became part of Yugoslavia after World War One, set his sights on creating an institution that would serve as an open forum for scientists from the East and West, especially from the United States and the Soviet Union.

Budinich and his colleagues at the University of Trieste were keen to locate the proposed centre in Trieste. World War Two had left this once-proud port city stranded at the southern edge of the “iron curtain”, a circumstance that was fuelling poisonous nationalist sentiments. One of the few remedies, envisioned by Budinich, was to establish cultural collaborations, especially in science, that would help part the curtain that had been drawn between East and West.

It was this vision of an international physics centre serving as an intellectual crossroads between north, south, east and west that gave the proposal its broad purpose and appeal. Nevertheless the debate over the utility of such an institution was fierce.

Critics contended that the goals of the proposed centre could be better met by establishing special research and training programmes for developing-world scientists within existing centres – for example, the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study in the United States or the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna in the Soviet Union (see p25). Others argued that the developing world should focus on more pressing social and economic concerns – for example, combating hunger or alleviating poverty. Still others maintained that physics conducted by third-world scientists would fall short of international standards, relegating the proposed institution to third-rate status.

Despite the opposition, Salam and Budinich’s persistence eventually won the day. After nearly three years of discussion and debate the IAEA board of governors decided to back the proposal, providing United Nations (UN) approval for the concept. At the same time the Italian government agreed to supply sufficient funding – some $275 000 annually for the first four years of the centre’s existence – to ensure that the initiative would be able to function, at least at a base level, during its early years. IAEA, in addition to providing the UN’s endorsement, agreed to provide $55 000 a year to ICTP. In 1970 the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) joined the effort as an additional partner.

The agreement, signed in 1963, between the Italian government and IAEA represented a sterling example of global co-operation – proof that governments and international organizations can work together on initiatives capable of achieving sustainable progress.

Given the events of the past few years, marked by a fraying of global alliances and an overall coarsening of the dialogue between nations, it is good to remember a time when our global community came together to advance the cause of international harmony and understanding. The business of ICTP is science – and more specifically physics and mathematics – but its “legacy for the future” extends far beyond the scientific community to our global society itself. That is just one more reason to celebrate the 40th anniversary of ICTP.