Le réseau ENLIGHT dynamise la thérapie par ions légers

ENLIGHT, Réseau européen de recherche sur la thérapie par les ions légers, a récemment tenu sa dernière réunion. Financé par l’UE pendant trois ans, le réseau avait pour mission de coordonner les recherches menées en Europe sur l’utilisation des faisceaux d’ions légers (hadrons) en radiothérapie. La réunion a fait ressortir les avancées dans ce domaine et le rôle-clé qu’a joué le réseau en rapprochant différents centres européens pour promouvoir la thérapie hadronique, en particulier à l’aide d’ions carbone.

The European Network for Research in Light Ion Therapy (ENLIGHT), which had its inaugural meeting at CERN in February 2002, was established to coordinate European efforts in using light ion beams for radiation therapy. Funded by the European Commission for three years, the network was formed from a collaboration of European centres, institutions and scientists involved in research, and in the advancement and realization of hadron-therapy facilities in Europe (see CERN Courier May 2002 p29). The final meeting took place in June in Oropa, an ancient sanctuary in the Italian Alps. Organized by the Italian foundation for hadron therapy, Fondazione per Adroterapia Oncologica (TERA), it was chaired by Ugo Amaldi, whose promotion of hadron-therapy facilities is highly valued and widely recognized.

The meeting went beyond providing a mere platform for discussion for the 100 scientists in ENLIGHT. Following immediately after the 10th Workshop on Heavy Charged Particles in Biology and Medicine (HCPBM), it became an international gathering for clinicians, radiobiologists, physicists and engineers, and provided an opportunity to demonstrate the latest developments in hadron therapy. There were presentations and discussions on the key areas outlined in the EU project: epidemiology and patient selection; clinical trials; radiation biology; beam delivery and dosimetry of ion beams; imaging; and the economics of hadron-therapy treatment.

Researchers already know that hadrons are an important alternative to photons for radiation therapy. Conventional radiation therapy with photon beams is characterized by energy release that decreases steeply after a maximum at a depth of 2-3 cm for typical beams. Hadrons, by contrast, release the highest density of energy at the end of their path. Therefore a beam of protons or light ions allows a highly tailored treatment of deep-seated tumours with millimetre accuracy, minimally damaging surrounding tissue.

ENLIGHT has been instrumental in bringing together different European centres to promote hadron therapy, in particular with carbon ions; to establish international discussions comparing the respective advantages of intensity-modulated radiation treatment (IMRT) with X-rays, proton and carbon therapies; and to address the ancillary equipment and methods necessary for such therapies. These efforts have included a study to compare the clinical data for proton therapy (at the Centre de Protontherapie, Orsay) and carbon-ion therapy (GSI) for certain types of tumour (chordomas and chondrosarcomas) at the base of the skull.

Carbon-ion therapy

Clinical trials are conducted for a specific tumour type and location to identify the total amount of dose to be delivered, the optimal number of fractions and the possible combination with other treatments. (Fractions are the number of radiation treatments in which the total required dose is delivered). Experience gained from clinical results obtained with carbon ions at the Heavy Ion Medical Accelerator in Chiba (HIMAC) in Japan and at GSI shows that these particles are very effective at treating tumours as they produce irreparable neighbouring multiple-strand breaks in the double helix of DNA, mainly in the region of the tumour cells; furthermore, post-treatment survival rates are improved.

A group of clinicians from HIMAC presented some remarkable results at the meeting. They conducted trials on “non-small” lung cancers in which the number of fractions was decreased from 16 to 4; for small lung and liver cancers, treatments are carried out in only one or two irradiation sessions; prostate cancer is treated in fewer than 20 sessions, while approximately 30 are needed for proton therapy and 40 for conventional radiotherapy. In the Japanese carbon-ion facility the average number of fractions is reduced to 13, less than half of what is needed for proton or traditional radiotherapy treatment. This simultaneously decreases the patient’s discomfort, increases the number of patients that can be treated per year and lowers the cost of the total treatment.

With two new hadron-therapy centres soon to become operational in Heidelberg and Pavia, analysing the cost of ion therapy versus traditional treatment is an important issue. A session of the meeting was devoted to discussing the economic aspects of facilities and treatments, with several European estimates indicating the cost of a hadron-therapy centre to be in the order of €100 million. A study carried out at the German cancer research centre, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ), has compared the treatment cost of chordoma at the base of the skull, in which surgical removal is followed by conventional radiotherapy or carbon-ion radiotherapy. A primary 20-fraction treatment with carbon ions has an estimated cost of €20,000-25,000, more than primary conventional radiotherapy. However, hadron therapy becomes more cost-effective in the long term, as it makes recurring tumours less likely. Furthermore, the cost of carbon-ion therapy could decrease if there are fewer fractions.

The meeting also looked at the principles of treatment optimization and planning. The centre at PSI in Villigen has studied treatment planning for intensity-modulated proton treatment (IMPT), in which three or four fields with complex particle fluences combine to create a uniform dose in the treatment volume. In this way, it is possible to optimize the sparing of healthy tissue. A similar project is under study for carbon ions at GSI.

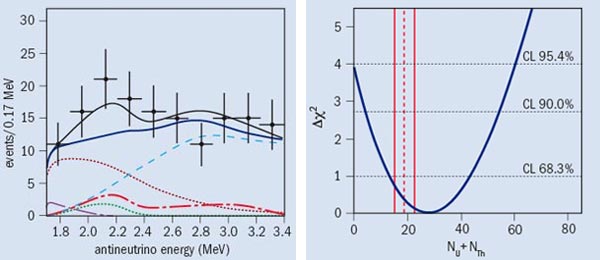

Studies are under way to investigate the implementation of online positron emission tomography (PET) imaging in carbon-ion facilities. The technique uses the positrons emitted by the nuclear fragments of the treatment beam and the imaging systems of the conventional PET. It offers a non-invasive method for comparing in situ the planned dose and the dose delivered. The data can be used to correct and redesign planning for subsequent treatment fractions. Work on online PET in proton therapy was also presented.

The meeting also learned of a project that compares the dose distribution achieved with X-rays, protons and carbon ions. The treatment-plan systems available for IMRT – passive scattering and spot scanning for proton beams, and raster scanning for carbon ion beams – are being used to compare the effectiveness of the different radiations in delivering the dose to the target volume while sparing the organs at risk. When implemented, this could become a fundamental daily reference tool for radiotherapists and oncologists.

Facilities for the future

There are a variety of facilities with highly specialized beams available for studying specific radiobiological aspects in Europe that could be more usefully organized on a wider basis. This was discussed during the meeting, with proposals ranging from identifying a single European facility for studying radiobiology in hadron therapy to the creation of a European network of existing and new facilities. In both cases, the EU framework programmes are seen as potential funding sources, with a common European “Experiments Committee” to approve experiments and allocate beam time.

In the ENLIGHT network the characteristics of synchrotron-based hadron-therapy centres have been studied to optimize designs for a possible second-generation hadron-therapy facility. The work has involved the optimization of injection and extraction systems, the beam diagnostic, monitoring of the treatment, and the dosimetry.

In the final session, the role and effect of the ENLIGHT initiative and future perspectives were discussed. It was acknowledged that the network has certainly succeeded in focusing the attention of European countries on the importance of hadrons in cancer treatment. Four national centres have been approved: Heidelberg Ion Therapy (HIT); the Centro Nazionale di Adroterapia Oncologica (CNAO) in Pavia; MedAustron in Wiener Neustadt; and ETOILE in Lyon. There is an increasing interest in further initiatives and more countries are expressing interest in creating national projects, in particular Sweden, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain and the UK.

Interest in the industry is increasing rapidly. Several companies with experience in proton accelerators are preparing to launch carbon-therapy machines on the market. For example, Roberto Petronzio, president of the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN), announced an agreement between INFN, Ansaldo Superconduttori and ACCEL to develop and launch a 250 MeV/u superconducting cyclotron suitable for protons and carbon ions (see CERN Courier September 2005 p9).

The interest in carbon-ion therapy is also crossing the Atlantic back to the US, where the initial pioneering studies using hadrons began more than 50 years ago at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. Although the most recent facilities installed in the US are based on proton accelerators, there is growing interest in using heavier ions, and building dual systems for both proton and carbon ions is becoming more likely.

A major success of ENLIGHT has been the creation of a multidisciplinary platform, uniting traditionally separate communities so that clinicians, physicists, biologists and engineers with experience in carbon ions and protons work together. It was unanimously acknowledged that ENLIGHT has been a key catalyst in building a European platform and pushing hadron therapy forward. Discussions are under way to continue this fruitful network, as it is felt that ENLIGHT is a crucial ingredient for progress and therefore should be maintained and broadened.

• ENLIGHT consists of the following members: the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO); CERN; the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC); GSI; the Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ); the Fondazione per Adroterapia Oncologica (TERA); the Karolinska Institutet; the ETOILE project; the Forschungszentrum Rossendorf (FZR), Dresden; the Hospital Virgen de la Macarena, Sevilla; and Charles University, Prague.