Bent crystals

Over the past decade, the understanding of particle steering by a bent crystal lattice has progressed very well, and in particular the accelerator applications of the bent-crystal channelling technique have greatly expanded. Crystal bending and extraction of particle beams has become an established technology at high-energy accelerators, and with the approaching start-up of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, crystal-channelling techniques are providing further applications that are useful in the multi-tera-electron-volt range. One new application proposes bending the LHC protons (or ions) by a huge angle of 1-20 ° in the 0.45-7 TeV energy range using a bent single crystal of silicon or germanium. This would allow calibration of the calorimeters in the CMS (or ATLAS) detector in situ, using an LHC beam of precisely known energy. The simulations presented at the workshop show that such an application at the LHC is feasible. The workshop also reported results from the experiment at the Institute for High Energy Physics (IHEP), Protvino, on crystal bending of 70 GeV protons by 9 ° (150 mrad) and its application for beam delivery during 1994-2004.

At lower particle-accelerator energies, crystal channelling can be used to produce low-emittance beams useful for medical and biological applications. The success in bending beams of less than 1 GeV was reported from the Beam Test Facility of the INFN’s Laboratori Nazionali di Frascati (LNF). Here, a positron beam of about 500 MeV provides the right energy scale for using the facility as a test bench for possible future applications of crystal techniques with light ions in medical machines. This study was made possible through the support of Transnational Access to Research Infrastructure granted to LNF by the European Union as one of the major research infrastructures in Europe to give free access to researchers for the period 2004-2008. The advances in crystal micro-technology for producing micro-beams for possible future applications in radiobiology and medicine was also reported by the INFN-IHEP collaboration. This work covers the range from lower energies (kilo-electron-volts and mega-electron-volts) to higher energies (giga-electron-volts) and compares channelling techniques with alternative ones.

From Japan, a collaboration from Hiroshima University and KEK reported on an experiment on electron-beam deflection with channelling in silicon crystals at the 150 MeV electron ring of the university’s Relativistic Electron Facility for Education and Research. The group plans tests with bent crystals at KEK’s Proton Synchrotron and aims to apply crystal deflection of high-energy beams at the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Centre, the 50 GeV high-intensity proton machine currently under construction in Japan.

Undulators and targets

While bent (and also focusing) crystals are well-known tools in accelerators, crystal undulators are just being introduced into experiments. Channelling undulators offer sub-millimetre periods and magnetic fields of the order of 1000 T. Samples of crystal undulators have already been manufactured and tested with X-rays and in channelling proton beams. Now tests using positron beams have been started at IHEP Protvino and at CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron, and are also planned at LNF. The first data from the experiment on positron radiation in a crystal undulator at IHEP were presented at the workshop.

The Yerevan Physical Institute presented calculations on radiation produced by 20 MeV electrons channelled in the crystallographic planes of quartz, both with and without periodic deformations. The institute also plans experiments to study the influence of external fields on channelling radiation.

Intense positron sources using crystal effects are another application of strong coherent fields. A number of talks reported on the theories of coherent radiation and pair production in ordered matter, and CERN’s WA103 collaboration reviewed the experimental progress in the field. The KEK-Tokyo-Tomsk-Paris collaboration reported a study of positron production from a thick silicon-crystal target using 8 GeV channelling electrons with high bunch charges.

For the future, many interesting directions are foreseen in the field

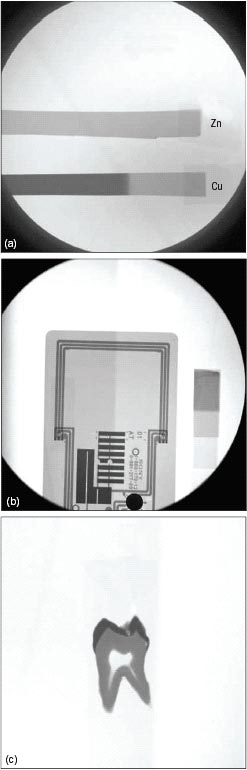

The workshop marked two decades since the experimental discovery of parametric X-ray radiation (PXR) in Tomsk in 1985: the radiation is generated by the motion of electrons inside a crystal, such that the energy intensity of the radiation depends on the parameters of the crystal structure. PXR has since been a subject of experimental and theoretical research and possible applications at accelerators, and was a subject in many talks at the workshop. A team working at Nuclotron at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna has reported the first observation of PXR from moderately relativistic nuclei in crystals. A nice example of an application is a tunable monochromatic X-ray source based on PXR developed at the Laboratory for Electron Beam Research and Application in Nihon University, Japan. So far the main use of the X-rays there has been in radiography for biological samples such as teeth or bones (figure 1). The contrast of the images was controlled with precise changes of the X-ray energy, a great advantage of a system that uses a PXR beam.

For the future, many interesting directions are foreseen in the field. A great deal of effort worldwide is being put into crystal radiation research and applications. Further progress is expected in applications using bent crystals for beam steering at accelerators. It will be an ideal opportunity to take full advantage of the channelling-crystal potentialities at the LHC and other high-energy accelerators, making crystals to serve for both collimation and extraction. The opportunity to have an extracted beam at a multi-tera-electron-volt machine should stimulate more research at the highest energies into particle interactions with aligned atomic lattices. The first crystal-channelling undulators and their initial tests with positron beams should proceed to the realization of novel radiation sources; thus, new positron-channelling experiments on undulator radiation are eagerly awaited.

The success of the workshop is reflected both in the level of participation, with around 40 specialists coming from different geographical areas, such as Europe, Japan and the former USSR, and in the high quality of the presentations. The resulting papers will be published as a special issue of Nuclear Instruments and Methods B, covering nearly all topics of current interest in channelling and radiation in aligned periodic structures at relativistic energies.