The lightweight axion is one of the major candidates for dark matter in the universe, along with weakly interacting massive particles. It originally arrived on the scene about 30 years ago to explain CP conservation in QCD, but there has never been as much theoretical and experimental activity in axion physics as there is today. Last year, the PVLAS collaboration at INFN Legnaro reported an intriguing result, which might indicate the detection of an axion-like particle (ALP) and which has triggered many further theoretical and experimental activities worldwide. The international workshop Axions at the Institute for Advanced Study, held at Princeton on 20–22 October 2006, brought together theorists and experimentalists to discuss current understanding and plans for future experiments. The well organized workshop and the unique atmosphere at Princeton provided ideal conditions for fruitful discussions.

In 2006, the PVLAS collaboration reported a small rotation of the polarization plane of laser light passing through a strong rotating magnetic dipole field. Though small, the detected rotation was around four orders of magnitude larger than predicted by QED (Zavattini et al. 2006). One possible interpretation involves ALPs produced via the coupling of photons to the magnetic field.

Combining the PVLAS result with upper limits achieved 13 years earlier by the BFRT experiment at Brookhaven National Laboratory (Cameron et al. 1993) yields values of the ALP’s mass and its coupling strength to photons of roughly 1 MeV and 2 × 10-6 GeV-1, respectively (Ahlers et al. 2006). If the PVLAS result is verified, these two values challenge theory because a standard QCD-motivated axion with a mass of 1 MeV should have a coupling constant seven orders of magnitude smaller. Another challenge to the particle interpretation of the PVLAS result comes from the upper limit measured recently at CERN with the axion solar helioscope CAST, which should have clearly seen such ALPs. However this apparent contradiction holds true only if such particles are produced in the Sun and can escape to reach the Earth.

So far there is no direct experimental evidence for conventional axions. The first sensitive limits were derived about two decades ago from astrophysics data (mainly from the evolution of stars, where axions produced via the Primakoff effect would open a new energy-loss channel so stars would appear older than they are), and also from experiments searching for axions of astrophysical origin (cavity experiments and CAST for example) and accelerator-based experiments. The conclusions were that QCD-motivated axions with masses in the micro-electron-volt to milli-electron-volt range seem to be most likely – if they exist at all.

The combined PVLAS–BFRT result would fit well into these expectations if the coupling constant were not too large by orders of magnitude. Theoreticians have tried to deal with this problem and develop models in line with the ALP interpretation of the PVLAS data and astrophysical observations. There may be some possibilities involving “specifically designed” ALP properties. However, to the authors’ understanding, such attempts fail if the conclusion announced at the workshop persists: according to preliminary new PVLAS results, the new particle is a scalar, whereas conventional axions are pseudoscalars. Consequently either the interpretation of the data or the experimental results must be reconsidered.

Although the PVLAS collaboration has measured the Coutton–Mouton effect – birefringence of a gas in a dipole magnetic field – for various gases with unprecedented sensitivity, the workshop openly considered possible systematic uncertainties. While experimental tests rule out many uncertainties, others are still to be checked. For example, the relatively large scatter of individual PVLAS measurements and the influence of the indirect effects of magnetic fringe fields remain to be understood. The PVLAS collaboration is therefore planning further detailed analyses.

In search of ALPs

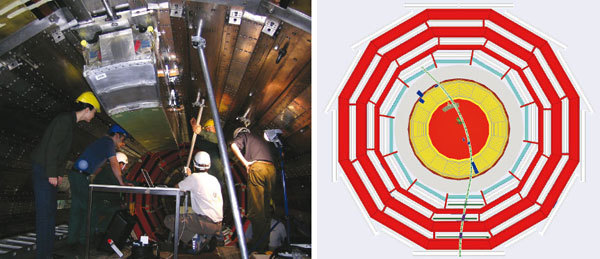

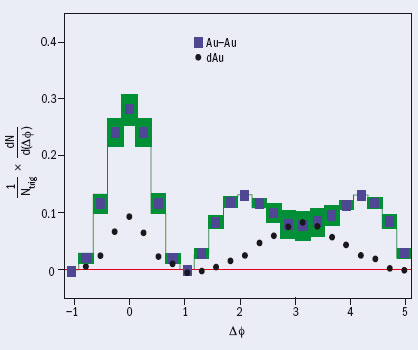

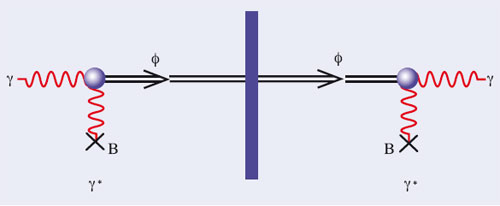

One clear conclusion is the need for more experimental data. A “smoking gun” proof of the PVLAS particle interpretation would be the production and detection of ALPs in the laboratory. In principle the BFRT collaboration has already attempted this in an approach called “light shining through a wall”. In the first part of such an experiment, light passes through a magnetic dipole field in which ALPs would be generated; a “wall” then blocks the light. Only the ALPs can pass this barrier to enter a second identical dipole magnet, in which some of them would convert back into photons (figure 1). Detection of these reconverted photons would then give the impression of light shining through a wall. The intensity of the light would depend on the fourth power of the magnetic field strength and the orientation of the light polarization plane with respect to the magnetic dipole field.

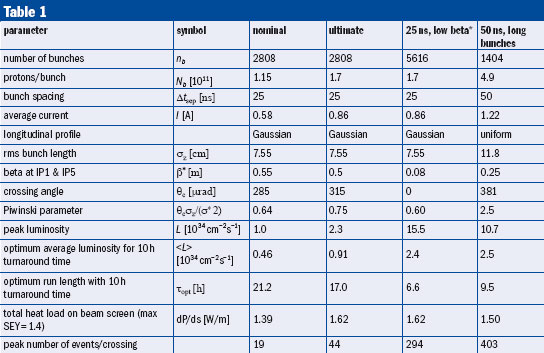

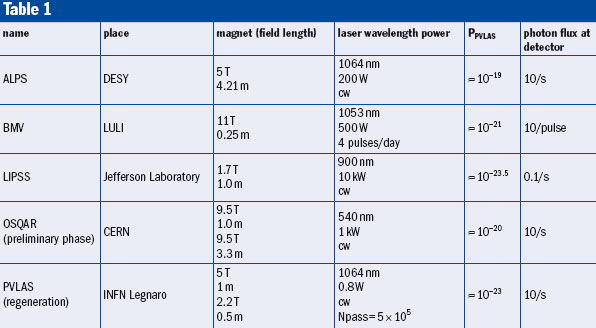

The PVLAS collaboration and other groups are planning a direct experimental verification of the ALP hypothesis. Table 1 provides an overview of some of the approaches presented at the workshop. Besides PVLAS the ALPS, BMV and LIPSS experiments should take data in 2007. BMV and OSQAR (as well as the Taiwanese experiment Q&A) will confirm directly the rotation of the light polarization plane that PVLAS claims. The BMV collaboration aims for such a measurement in late 2007.

Research during the coming year should therefore clarify the PVLAS claim in much greater detail. The measurement of a new axion-like particle would be revolutionary for particle physics and probably also for our understanding of the constituents of the universe. However, considering the theoretical difficulties described above, a different scenario might emerge. Within a year from now we might be confronted both with an independent confirmation of the PVLAS result on the rotation of the light polarization plane, and simultaneously with only upper limits on ALP production by the light shining through a wall approaches. This situation would require new theoretical models.

The planned experiments listed in Table 1 do not have the sensitivity to probe conventional QCD-inspired axions. In the near future, CAST will be the only set-up to touch the predictions for solar-axion production. The workshop in Princeton, however, heard about other promising experimental efforts to search directly for axions or other unknown bosons with similar properties. These studies use state-of-the-art microwave cavities – for example, as in ADMX in the US, which is looking for dark-matter axions – or pendulums to search for macroscopic forces mediated by ALPs.

On the theoretical side, as we mentioned above, attempts to interpret the PVLAS result have generated some doubts on the existence of a new ALP. Perhaps micro-charged particles inspired by string theory might provide a more natural explanation of the PVLAS result. Researchers are thus discussing novel ideas of how to turn experimental test benches for accelerator cavity development into sensitive set-ups to test for micro-charged particles. However, as Ed Witten explained in the workshop summary talk, string theories also predict many ALPs, so perhaps we are on the cusp of discovering an entire new sector of pseudoscalar particles.

In summary, it is clear that small-scale non-accelerator-based particle-physics experiments can have a remarkable input to particle physics. Stay tuned for further developments.

The authors wish to thank the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study for the warm hospitality, and especially Raul Rabadan and Kris Sigurdson for their perfect organization of the workshop.