The origin of ultra-high-energy cosmic rays (UHECR) observed at energies above 1019 eV is a mystery that has stimulated much experimental and theoretical activity in astro-physics. When cosmic rays penetrate the atmosphere, they produce showers of secondary particles and corresponding radiation, which in principle yield information on the particle tracks, energy and origin of the primary cosmic rays. The CODALEMA experiment in Nançay has recently measured the radio-electric-field profiles associated with these showers on an event-by-event basis. These novel observations are directly connected to the shower’s longitudinal development, which is related to the nature and energy of the incident cosmic ray.

There have been previous partial studies of radio emission from showers, so why is this result so promising? The UHECR flux is very low (a few per square kilometre per century), so the largest detector arrays are square kilometres in area to detect secondaries at ground level combined with various other techniques, such as the fluorescence emission. However, the latter method is limited to the optical domain, where the need for moonless skies and appropriate environmental conditions results in a maximum duty cycle of only about 10%. So, the radio detection technique offers an interesting if challenging alternative (or complementary) method in which one antenna array can provide a very large acceptance and sensitive volume adequate to characterize rare events, such as UHECR.

There is also another important argument for the radio technique: because the distance between radiating particles is several times smaller than typical radio wavelengths, the individual particles radiate in phase. This will result in a coherent type of radio emission dominating all other forms of radiation, with a corresponding electromagnetic radiated power proportional to the square of the deposited energy. In air, the coherent radiation will build up at frequencies up to several tens of megahertz, while in dense materials, more compact showers can result in coherence radiation up to several gigahertz. Gurgen Askar’yan first suggested the production of radio emission in air showers in 1962, and some observations were reported in the 1960 and 70s (Allan 1971, Gorham and Saltzerg 2001). The electronics available at the time made the measurements unreliable, however, and researchers abandoned the technique in favour of direct ground particle or fluorescence measurements.

High-performance digital signal-processing devices have now made feasible the sampling of radio-frequency (RF) waveforms with large frequency bandwidth and high time-resolution, depending on the nature of the primary cosmic ray. Exploiting these new possibilities, the SUBATECH Laboratory, Nantes, and the Paris Observatory have developed the CODALEMA (Cosmic ray Detection Array with Logarithmic Electro-Magnetic Antennas) experiment on the site of the Nançay Radio Observatory.

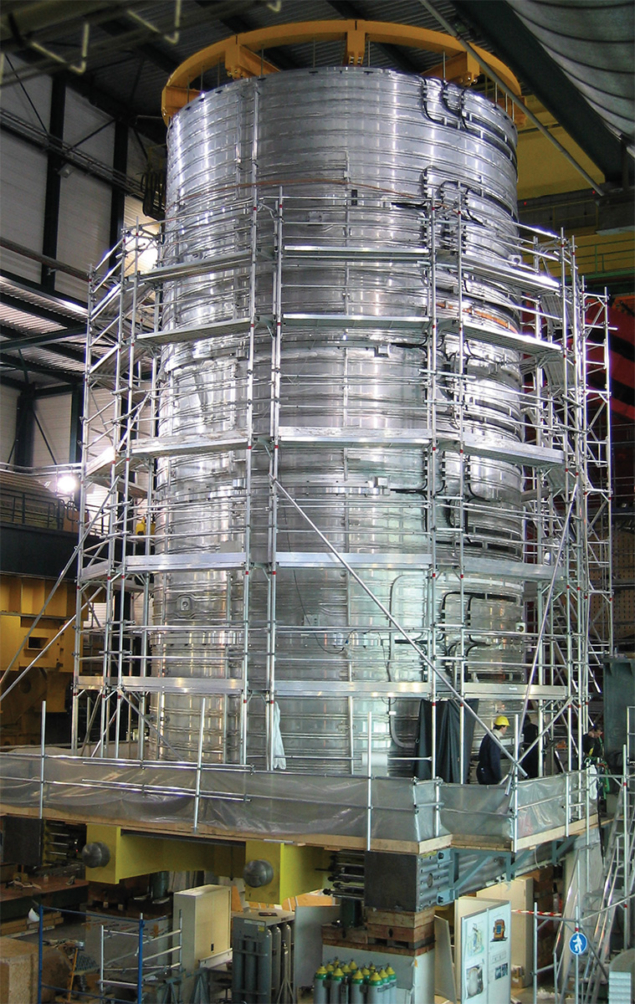

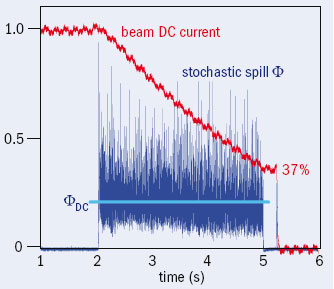

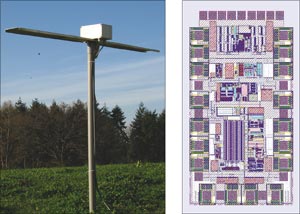

For its first phase, CODALEMA has used some of the 144 log-periodic antennas of the decametric array of the Nançay Observatory distributed along a 600 m baseline. All the antennas are band-pass filtered (24–82 MHz) and linked, after RF signal wide-band amplification, to fast-sampling digital oscilloscopes (figure 1).

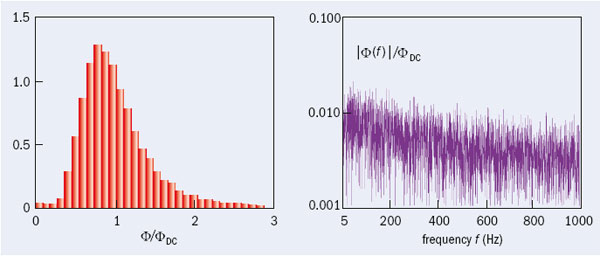

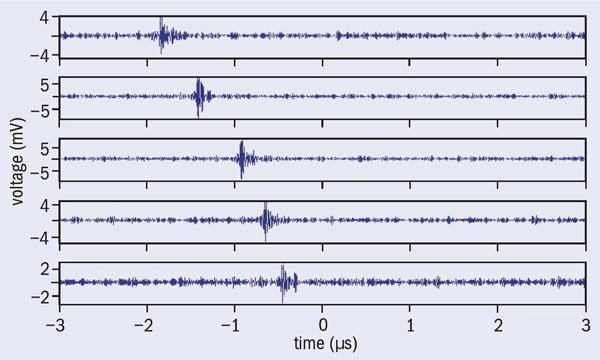

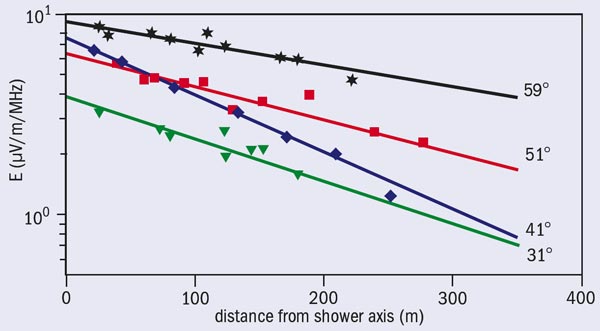

In its first running period, CODALEMA has established the appropriate conditions for the analysis of the antenna data, either in stand-alone mode or in coincidence with a set of particle detectors acting as a trigger. Figure 2 shows four cosmic-ray events identified at different zenith angles. It illustrates how the results reveal the dependence of the electric field on the distance of the antenna to the shower impact (in metres) at energies around 1017 eV. They show for the first time the richness of the information contained in the longitudinal shower development measured by radio detection.

First, the device is sensitive to amplitudes down to 1 μV/m/MHz, which is free from the fluctuations in the number of particles encountered in particle detectors. This allows detailed analysis of the field amplitude and its dependence on the energy and nature of the incident cosmic ray. It is remarkable that this sensitivity is carried over distances presumably greater than 600 m from where the shower hits the ground. The clear zenith angle dependence of the field profile illustrates the large angular acceptance of the array. This demonstrates for the first time the sensitivity of this detection method to the development of the shower, related to sequences of charge generation. Additionally, a Fourier transform analysis of the signal revealed a possible frequency dependence of the signal with impact parameter, a quantity strongly connected to the physical characteristics of the air shower.

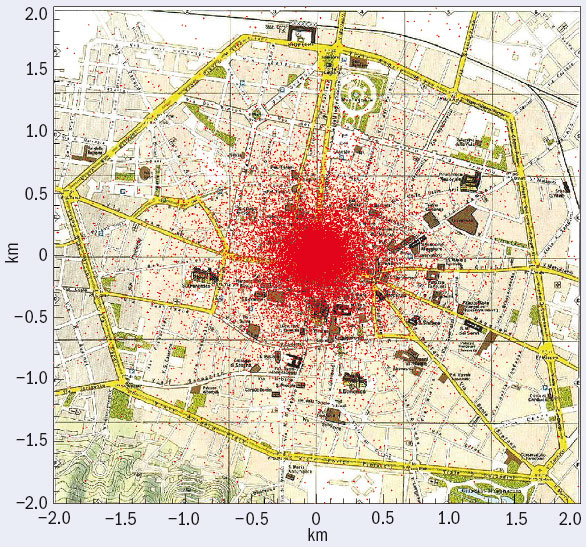

At last, the study of the stand-alone antenna mode has clearly established that the transient character of the radio signal can be safely used to determine the arrival direction (with an accuracy of around 0.7°) and to reconstruct full event waveforms.

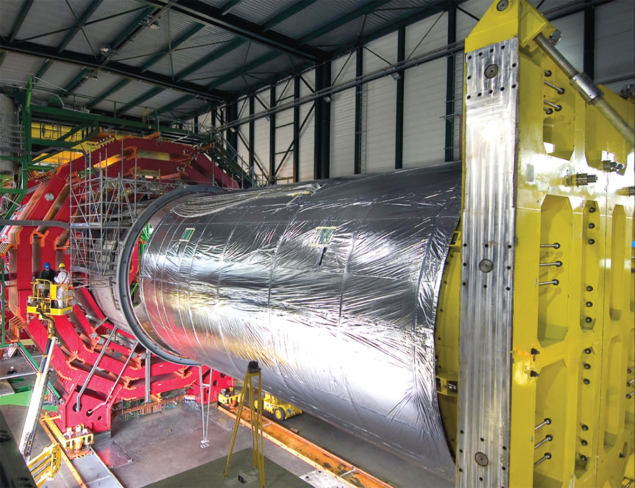

These results clearly demonstrate the interest in a complete re-investigation of the radio detection of UHECR that Askar’yan first proposed in the 1960s. Only two experiments in the world have undertaken this type of analysis with atmosphere showers: CODALEMA and the LOPES experiment, which is studying the same RF domain (Isar et al. 2006). The latter works as an extension of the triggering multi-detector set-up Kascade-Grande in Karlsruhe. Other active experiments use dense materials such as ice, salt or lunar regolith, and therefore study higher frequency domains; these include RICE and ANITA (Antarctic), FORTE satellite (Greenland), SALSA (Mississippi) and GLUE (NASA-Goldstone).

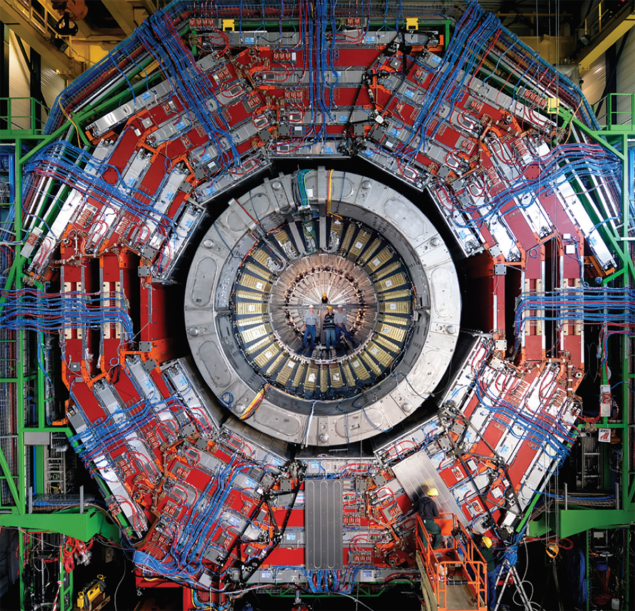

In addition, the CODALEMA results indicate specific features that encourage the use of this technique as a complementary method to experiments based on large ground detector arrays, such as the Pierre Auger Observatory. The CODALEMA collaboration is currently investigating this possibility. In addition, it is considering the exploitation of the large zenithal acceptance for the challenging study of very inclined showers, which correspond to large slant depths in the atmosphere (or Earth). For example, while suppressed by the Earth’s opacity and barely accessible to other techniques, high-energy neutrinos can interact at any point along such trajectories, producing τ particles and subsequent detectable “young” showers in the atmosphere. Another interesting application is the characterization of distant storms and very energetic atmospheric radiation events of currently unknown origin. An upgraded experimental set-up has been running since November 2006, consisting of 16 antennas with new active wide-bandwidth dipoles together with 13 particle detectors to allow shower-energy determinations for calibration purposes.

• The CODALEMA collaboration comprises three laboratories from the Institut National de Physique Nucléaire et de Physique des Particules (IN2P3): SUBATECH/Nantes, LPSC/Grenoble LAL/Orsay, two laboratories from the Institut National des Sciences de l’Univers (INSU): Observatoire de Paris/LESIA and LAOB/Besançon; the LPCE/Orleans CNRS laboratory; and the private ESEO Angers Institute.