Suppose, as the villain of a story, you absolutely needed to transport a macroscopic amount of antimatter, for whatever sinister purpose. How would you go about it and could you smuggle it, for example, into the Vatican catacombs? The truth is that we will probably never have a macroscopic amount of antimatter for such a scenario to ever become reality.

According to the preface to the popular novel Angels and Demons (2000), author Dan Brown was apparently inspired by the imminent commissioning of CERN’s “antimatter factory”, the Antiproton Decelerator (AD). The real-life AD has now been fully operational for about five years, and the experiments there have produced some notable physics results. One of the big stories along the way was the synthesis in 2002 of antihydrogen atoms by the ATHENA and ATRAP collaborations.

This feat was an important step towards one of the ultimate goals of everyday antimatter science: precision comparisons of the spectra of hydrogen and antihydrogen. According to the CPT theorem, these spectra should be identical. To get an idea of what precision means in this context, take a look at the website of 2005 Nobel Laureate Theodor Hänsch, which has the following cryptic headline: f(1S–2S) = 2 466 061 102 474 851(34) Hz. This may look like a cryptic puzzle appearing in Brown’s fiction, but it simply means that the frequency of one of the n = 1 to n = 2 transitions in hydrogen has been measured with an absolute precision of about 1 part in 1014. This is impressive, but where do we stand with antihydrogen?

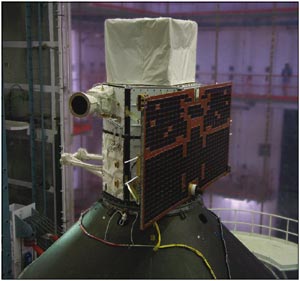

Storing antihydrogen

Image credit: N Madsen/Swansea.

Both ATHENA and ATRAP produced antihydrogen by mixing antiprotons and positrons in electromagnetic “bottles” called Penning traps. Penning traps feature strong solenoidal magnetic fields and longitudinal electrostatic wells that confine charged particles. The antiprotons come from CERN’s AD, and the positrons come from the radioactive isotope 22Na. The whole process involves cleverly slowing, trapping, and cooling both species of particles (Amoretti et al.. 2002 and Gabrielse et al.. 2002). But here’s the rub: when the charged antiproton and positron combine, the neutral antihydrogen is no longer confined by the fields of the Penning trap, and the precious anti-atom is lost. The ATHENA experiment demonstrated antihydrogen production because it could detect the annihilation of the anti-atoms when they escaped the Penning trap volume and annihilated on the walls.

To study antihydrogen using laser spectroscopy, anti-atoms need to be sustained for longer. In the 1s–2s transition mentioned above, the excited state (2s) has a lifetime of about a seventh of a second; while in ATHENA, an anti-atom would annihilate on the walls of the Penning trap within a few microseconds of its creation. Thus, the next-generation antihydrogen experiments include the provision for trapping the neutral anti-atoms that are produced in a mixture of charged constituents.

The Antihydrogen Laser Physics Apparatus (ALPHA) collaboration has recently commissioned a new device designed to trap the neutral anti-atoms. ALPHA takes the place of ATHENA at the AD and features five of the original groups from ATHENA (Aarhus, Swansea, Tokyo, RIKEN and Rio de Janeiro) plus new contributors from Canada (TRIUMF, Calgary, UBC and Simon Fraser), the US (Berkeley and Auburn), the UK (Liverpool) and Israel (Nuclear Research Center, Negev).

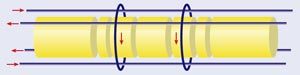

Neutral atoms – or anti-atoms – can be trapped because they have a magnetic moment, which can interact with an external magnetic field. If we build a field configuration that has a minimum magnetic field strength, from which the field grows in all directions, some quantum states of the atom will be attracted to the field minimum. This is how hydrogen atoms are trapped for studies in Bose–Einstein condensation (BEC). The usual geometry is known as an Ioffe–Pritchard trap. A quadrupole winding and two solenoidal “mirror coils” produce the field to provide transverse and longitudinal confinement, respectively. The image above also shows the electrodes that provide the axial confinement in the Penning trap for the charged antiprotons and positrons. The idea is that the antihydrogen produced in the Penning trap is “born” trapped within the Ioffe–Pritchard trap – if its kinetic energy does not exceed the depth of the trapping potential.

This is a big “if”. A ground-state hydrogen atom has a magnetic moment that gives us a trap depth of only about 0.7 K for a magnetic well depth of 1 T. The superconducting magnetic traps that we can build and squeeze into our experiments will give 1–2 T of well-depth for neutral atoms. All antihydrogen experiments to date occur in devices cooled by liquid helium at 4.2 K, but there are strong indications that the antihydrogen produced by direct mixing of antiprotons and positrons is warmer than this, with temperatures of at least hundreds of kelvin. ATRAP has devised a laser-assisted method of producing antihydrogen that May give colder atoms, but their temperature has not yet been measured. (Note that the highly excited antihydrogen atoms produced in both experiments can have significantly larger magnetic moments, thus experiencing higher trapping potentials. The trick, then, is to keep them around while they decay to the ground state.) Both groups are investigating new ways to produce colder anti-atoms, and the 2007 run at the AD (June–October) promises to be revealing.

Designer magnets

A second important issue facing both collaborations is the effect on the charged particles of adding the highly asymmetric Ioffe–Pritchard field to the Penning trap. Penning traps depend on the rotational symmetry of the solenoidal field for their stability. As ALPHA collaborator Joel Fajans of Berkeley initially pointed out, the addition of transverse magnetic fields to a Penning trap can be a recipe for disaster, leading either to immediate particle loss, or to a slower, but equally fatal, loss due to diffusion. Fajans’ solution, adopted by the ALPHA collaboration, is to use a higher-order magnetic multi-pole field for the transverse confinement. A higher-order field can, in principle, provide the same well-depth as a quadrupole while generating significantly less field at the axis of the trap, where the charged particles are confined.

To construct such a magnet, the ALPHA collaboration surveyed the experts in fabrication of superconducting magnets for accelerator applications. It turns out that the Superconducting Magnet Division at the Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) had previously developed a technique that is almost tailor-made to our needs. The key here is to use the proper materials in the construction of the magnet. To detect antiproton annihilations, ALPHA incorporates a three-layer silicon vertex detector similar to those used in high-energy experiments. However, the annihilation products (pions) must travel through the magnets of the atom trap before reaching the silicon. Therefore, it is highly desirable to minimize the amount of material used in the magnet construction to minimize multiple scattering between the vertex and the detector. So bulky stainless-steel collars for containing the magnetic forces, as used in the Tevatron or the LHC, cannot be used.

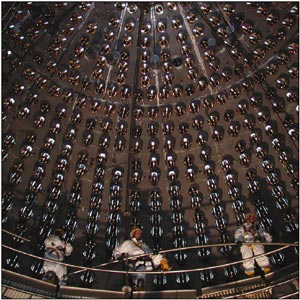

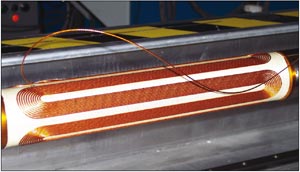

Image credit: J Escallier/BNL.

The Brookhaven process uses composite materials to constrain the superconducting cable that forms the basis of the magnet. Using a specially developed 3D winding machine, the team at BNL was able to wind an eight-layer octupole and the mirror coils directly onto the outside of the ALPHA vacuum chamber. The mechanical strength is provided by pre-tensioned glass fibres in an epoxy substrate. Only the superconducting cable is metal.

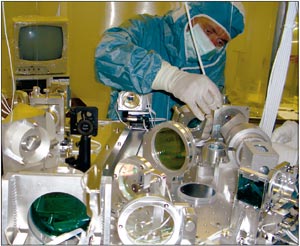

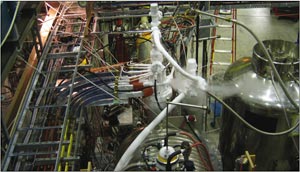

Image credit: N Madsen.

The new ALPHA device was designed and constructed during the AD shutdown of November 2004 to July 2006 and commissioned during the physics run at the AD in July–November 2006. The Brookhaven magnets performed beautifully, demonstrating that charged antiprotons and positrons can be stored in the full octupole field for times far exceeding those necessary to synthesize antihydrogen. We even made the first preliminary attempt to produce and trap antihydrogen in the full field configuration; but we have yet to observe evidence for trapping.

Meanwhile, the ATRAP collaboration worked hard to commission a new quadrupole trap for antihydrogen and succeeded in storing clouds of antiprotons and electrons in their new device. The 2007 physics run at the AD promises to be an exciting one for antihydrogen physics. Both ALPHA and ATRAP should have operational devices that are capable – in theory – of trapping neutral antimatter for the first time.

Back to Dan Brown

So let’s look at what is possible in experiments with antimatter today, leaving the speculation to aficionados of sci-fi and NASA. If you wanted to take antimatter to the offices of your national funding agency, you might consider taking some antiprotons, since most of the mass-energy of an antihydrogen atom is in the nucleus. This might be tempting, since our charged-particle traps are certainly deeper than those for neutral matter or antimatter. ATRAP and ALPHA initially capture antiprotons in traps with depths of a few kilo-electron-volts, corresponding to tens of millions of kelvin. But, density is an issue. A good charged-particle trap for cold positrons has a particle density of about 109 cm–3. Antiproton density is much smaller, but we’ll be optimistic and use this number. So to transport a milligram of antiprotons – of the order of 1021 particles – you would need a trap volume of 1012 cm3, or 106 m3. That means a cube 100 m wide, which will not fit in your luggage. Incidentally, a milligram of antimatter, annihilating on matter, would yield an energy equivalent to about 50 tonnes of TNT.

So, what about transporting some neutral antimatter? Neutral atom traps certainly have higher densities. The first BEC result for hydrogen at MIT reported a density in the order of 1015 cm–3 for about 109 atoms in the condensate. This is better, but still far less than a milligram, even if you can get the atoms from a gas bottle. The size of the trap is now down to 105 cm3, which is more manageable. Note, however, that the BEC transition in this experiment was at 50 μK – far below the 4.2 K that we hope to achieve with antihydrogen. Unfortunately, to get really cold and dense atomic hydrogen requires using evaporative cooling – throwing hot atoms away to cool the remaining ones in the trap. This implies damaging your lab before you send the surviving, trapped anti-atoms to their final, cataclysmic fate. And don’t forget that the total history of antiproton production here on Earth amounts to perhaps a few tens of nanograms in the past 25 years or so. Unfortunately, the antiproton production cross-section is unlikely to change.

How many anti-atoms can we trap? The Japanese-led ASACUSA experiment, using an extra stage of deceleration after the AD, can trap around a million of the 30 million decelerated anti-protons that the AD delivers every 100 s or so. Suppose we could make all of these into antihydrogen (in comparison, ATHENA achieved about 15%). The trapping efficiency for neutral anti-hydrogen is anybody’s guess at this point – we would be grateful for 1%. This is why the very notion of having a dense cloud of interacting antihydrogen atoms will bring a weary smile to the face of anyone working in the AD zone. Using the above figures, it would take us 1019 s – about 300 billion years – to accumulate just one milligram. One might also question if anyone could engineer a device reliable enough to safely contain an explosive quantity of anti-matter – not in my lab, thanks.

Back down to the sober reality here at CERN, we would be happy just to demonstrate trapping of antihydrogen in principle. This means initially trapping just a few anti-atoms – not making a BEC or antihydrogen ice. The future of our emerging field seems to depend on this, although ASACUSA is developing a plan to do spectroscopy on antihydrogen in flight. Time will tell which approach proves more promising. Two things are certain: the real technology of antimatter production and trapping lags far behind Dan Brown’s imagination; and the Vatican is safe from us.