Image credit: G Ricciardi.

The Second Workshop on Theory, Phenomenology and Experiments in Heavy Flavour Physics took place on 16–18 June in Anacapri, Capri, Italy – the same location as the first meeting in the series in May 2006. The aim of the series is to bring together theoreticians and experimentalists to develop a dialogue on phenomenological issues. The focus is on discussion and interaction among physicists who are active in the field. The topics this year focused on results, especially in B-physics, as well as exploring the potential for heavy flavour physics in both current and future experiments. With participation by invitation only, owing to space problems at the venue, the 60 or so attendees took part in many fruitful and lively discussions after the seminars and during the free time.

During the past decade flavour physics has witnessed unprece-dented experimental and theoretical progress, opening up the era of precision tests of the Standard Model. The quark and lepton sectors of the Standard Model have been subjected to a series of stringent tests, and it has become customary to look for violations of the Standard Model by using unitarity triangles. Updates of the unitarity triangle analyses were presented by Marco Ciuchini from Rome III/INFN and Jérôme Charles from the Centre de Physique Théorique, Marseille, for the UTfit and CKMfitter collaborations, respectively.

Such updates have been possible, not only because of the large amount of data now available, but also through theoretical progress (e.g. in lattice calculations). As Chris Sachrajda from the University of Southampton and Fermilab’s Paul Mackenzie reported, many approximations in typical lattice calculations have been overcome in recent years. Numerous simulations are now being performed that include quark–antiquark pairs, or a pion mass less than or equal to 300 MeV. Moreover, it is now becoming possible to generate configurations on lattices that are sufficiently fine and large to allow direct simulation of the charm quark.

An impressive amount of data has come from the two asymmetric e+e– B factories, PEP-II and KEKB, and their respective detectors, BaBar and Belle. The BaBar experiment concluded data taking in April 2008, having collected a total of 531 fb–1, of which 433 fb–1 was on the Υ(4S) peak, corresponding to about 470 × 106 BB pairs. In 2008, BaBar also collected 30 fb–1 on the Υ(3S) resonance and 14 fb–1 on the Υ(2S) resonance, with interesting results, such as the first evidence of the ηB – the long-sought bottomonium ground state. By the time of the workshop, Belle had accumulated about 850 fb–1, with 730 fb–1 on the Υ(4S) resonance.

The B factories have led the recent progress in knowledge of the unitarity triangle related to the B system, with angles α, β and γ (or φ2, φ1 and φ3). Christoph Schwanda from the Austrian Academy of Sciences and Giuseppe Finocchiaro from the Frascati National Laboratory/INFN reported on measurements of the angles and sides of the unitarity triangle. Paolo Gambino of Torino and Francesca Di Lodovico from Queen Mary, University of London, reviewed the main theoretical problems on the way to the long-sought precise theoretical inclusive determination of ΙVubΙ in the Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa (CKM) matrix.

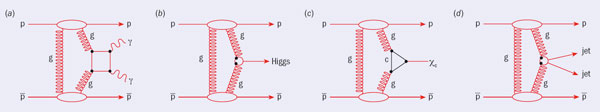

Golden modes and penguins

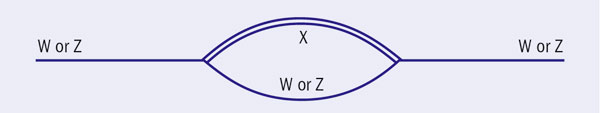

The B factories’ golden modes for the extraction of sin2β are b → cc decays, and the latest measurement from BaBar gives sin2β = 0.714 ± 0.032 ± 0.018, in agreement with the results from Belle. Other interesting decays are the b → sqq “penguin dominated” decays, those study of which is motivated not only by the measure of sin2β, but mostly by the search for new physics.

The angle α can be studied in b → uud modes, and its determination is made complicated by the addition of the b → d penguin amplitude to the b → uud tree one. The first measurements of the B0 → ρ0ρ0 decay confirm the indication that the effect of penguin amplitudes is relatively small in ρρ decays, which in fact yield the most stringent constraints on α.

A precise measurement of the unitarity angle, γ, unthinkable when the B factories started, is now becoming possible with the large statistics accumulated by the B factories. Several new measurements of B± → D0 K± transitions have appeared recently, and strong evidence for direct CP violation in these decays is building up.

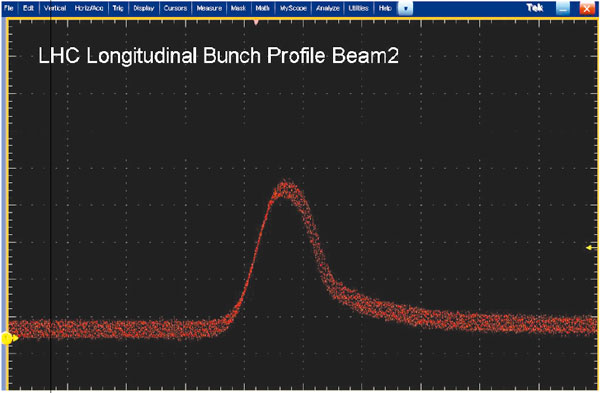

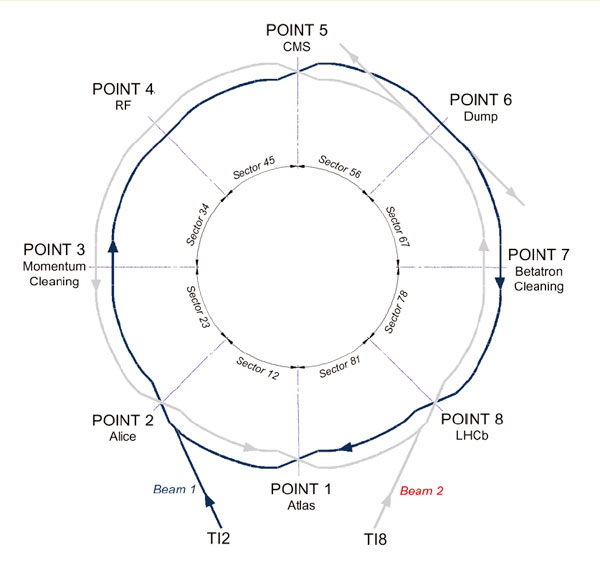

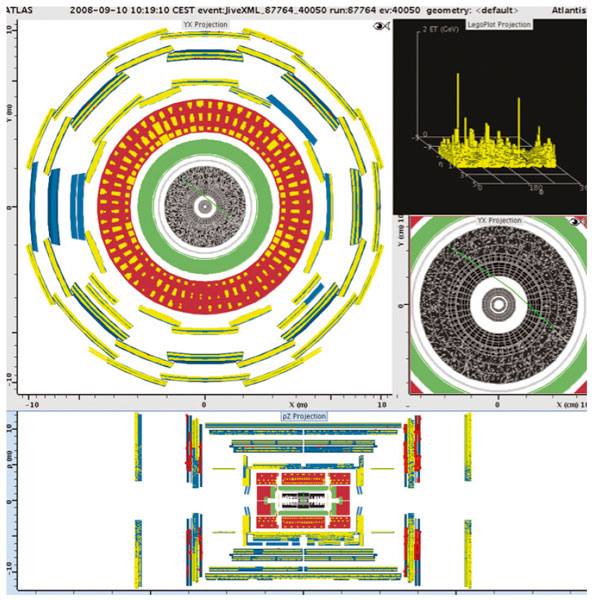

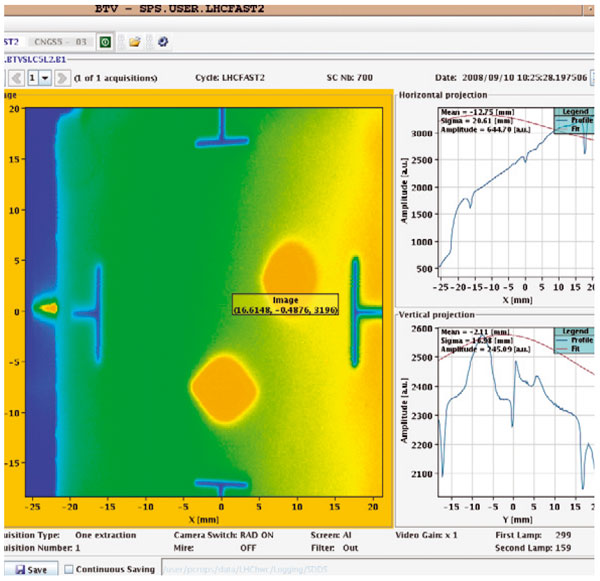

With the first runs of the LHC on the horizon, heavy flavour physics is entering a new phase.

Radiative penguin and leptonic B meson decays are another area of interest at B factories because they constitute a powerful probe of new physics. John Walsh of INFN/Pisa reported on recent experimental results in this field.

On the theory side, Luca Trentadue from Parma/INFN discussed the resummation of large logarithmic terms, which otherwise spoil the convergence of the perturbative series in the threshold region, in semileptonic charmed B decays. Cai-Dian Lü of the Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP), Beijing, analysed charmless two-body decays of the B mesons to light vector and pseudoscalar mesons in the soft-collinear effective theory.

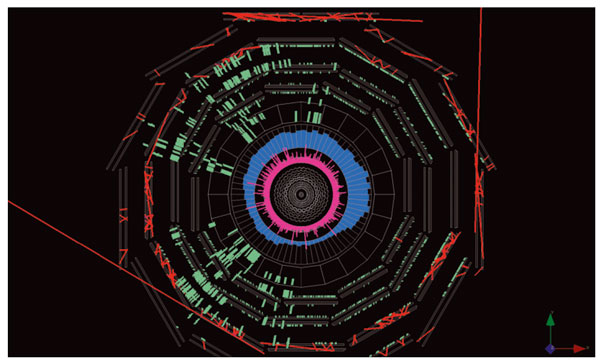

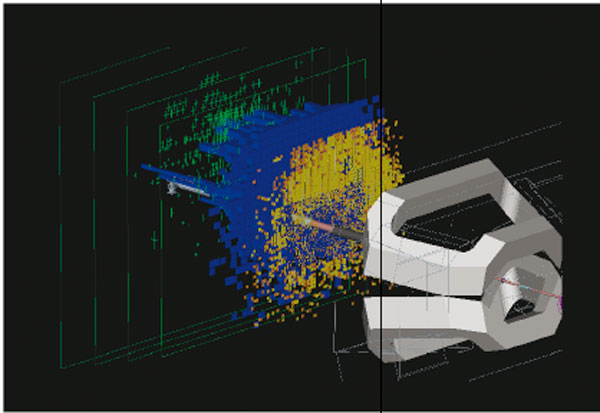

With the first runs of the LHC on the horizon, heavy flavour physics is entering a new phase. Natalia Panikashvili of Michigan, Andrei Starodumov of PSI and Stefania Vecchi of INFN/Ferrara described the role of flavour physics at the LHC for the ATLAS, CMS and LHCb experiments, respectively. Tobias Hurth of CERN/SLAC stressed that a large increase in statistics at LHCb for Bd → K *0μ+μ– will make measurements possible with much greater precision, allowing for an indirect search for new physics.

A main goal at the LHC is to measure CP-violating parameters, such as the Bs0 mixing phase, which in the Standard Model is predicted to be small, and could be another way of evincing new physics. Luca Silvestrini of INFN/Roma presented a new analysis that claims evidence of new physics through a Bs0 mixing phase, that is much larger than expected in the Standard Model. However, this had not been confirmed by independent analyses at the time of the workshop. Future data from the Tevatron or an extended Υ(5S) run of Belle may be of help in assessing the new results. Joaquim Matias of the Institute for High Energy Physics, Barcelona, discussed poss-ible strategies to measure the weak mixing phase of the Bs0 system using B mesons decaying into vectors.

Image credit: G Ricciardi.

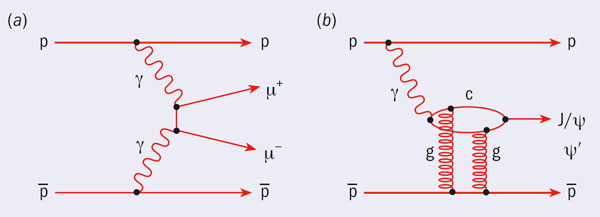

Charm physics, charm spectroscopy, CP violation in charm decays and searches for new physics were all discussed at length during the workshop. Ikaros Bigi of Notre Dame stated that comprehensive and detailed CP studies of charm decays provide a unique window into flavour dynamics. He emphasized the importance of LHCb in achieving the statistics required to find evidence of new physics in the charm sector. There is a powerful programme at LHCb for charm physics, which includes studying D0 mixing, observed for the first time at B factories in spring of last year, and CP violation in some specific decays. Pietro Colangelo of INFN/Bari discussed aspects of new charm spectroscopy and David Miller of Purdue presented the latest results from CLEO-c on W annihilation decays of the D+ and Ds+ mesons. The HERA electron–proton storage ring at DESY had come to the end of its scheduled operation roughly a year before the workshop, but data are still being analysed. Luis Labarga of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid presented recent results from the H1 and ZEUS collaborations on charm production and fragmentation, in addition to results on beauty production.

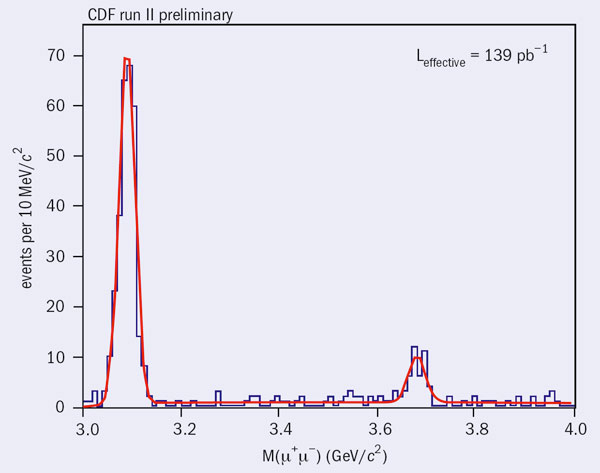

The experiment BESII, at the Beijing Electron Positron Collider has accumulated 5.8 × 107 J/ψ events, 1.4 × 107 ψ(2S) events and 35.5 pb–1 ψ(3770) data. Xiaoyan Shen of IHEP reported on recent results, which include the observation of the Υ(2175) in the J/ψ → ηφf0(980) decay. In the past few years a wealth of new experimental results on heavy quarkonia and exotic states has become available. Riccardo Faccini of Rome “La Sapienza”/INFN summarized recent developments in the search for excited states of the scalar nonet among the light mesons, and reviewed the experimental evidence for new states. Ruslan Chistov of the Institute of Theoretical and Experimental Physics, Moscow, discussed the experimental status of X, Y and Z states at B factories. More new states, decays and production mechanisms have been discovered in the past few years than in the previous 30 years. Besides the regular quarkonium states (mostly quark–antiquark states), new exotic states have been found the composition of which (molecule, tetraquark, hybrids&ellip;) is currently the centre of a lively debate. It was the subject of a dedicated round table at the workshop, chaired by Nora Brambilla of Milan, with Antonello Polosa of INFN/Rome, Joan Soto of Barcelona and Antonio Vairo of Milan.

Flavour for all

There were many lively discussions on the role of flavour to evince new physics. Andrzej Buras of the Technical University of Munich reviewed several main results on flavour physics beyond the Standard Model, analysing in particular flavour and CP-violating processes in models with supersymmetry, “littlest Higgs” and extra dimensions. Ulrich Nierste of Karlsruhe summarized the role of the decays B0 → μ+μ–, B+ → τ+ντ and B → D τ ντ in the hunt for new Higgs effects in the minimal supersymmetric Standard Model. Flavour and precision physics in the Randall–Sundrum model were the topics of discussion for Matthias Neubert of the Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, while Jernej Kamenik of INFN/Frascati talked about phenomenology in the context of minimal flavour violation.

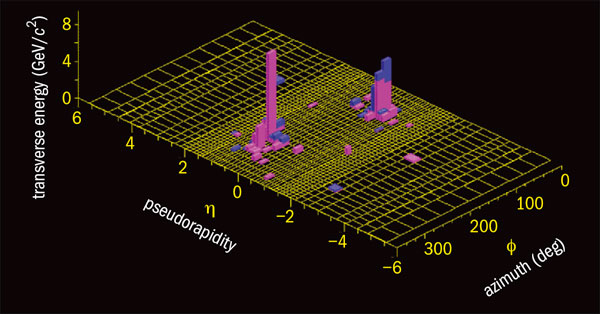

While waiting for the LHC, Fermilab’s Tevatron has not only demon-strated the possibility of B-physics at hadron machines but also produced measurements that are highly competitive and complementary to those of the B factories. In particular, this was via the unique access that hadron machines have to the Bs sector. Vaia Papadimitriou of Fermilab and the CDF experiment, and Brad Abbott of Oklahoma and D0, presented the latest measurements on the production, spectroscopy, lifetimes and branching fractions for B mesons, B baryons, and quarkonia. Theoretical issues for the measurement of the top mass using jets, and implications for measurements of the top mass at the Tevatron, were discussed by Iain Stewart of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Monte Carlo programs have already proved indispensable for making exclusive theoretical predictions at the Tevatron. Christian Bauer from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory presented an improved Monte Carlo framework (GenEvA) mainly based on a new notion of phase space.

Tom Browder of Hawaii and Marcello Giorgi of INFN/Pisa made a strong science case for continued heavy flavour physics measurements at future Super-B machines, underlining their complementarity to the LHC programme. One focus for the Super-B factories would be studying, and possibly discovering, new sources of flavour-changing neutral currents and CP-violation. There are plans for a Super-B factory at KEK in Japan based on the existing KEK accelerator and Belle detector, as well as a proposal for a laboratory in Italy, the SuperB project. In both cases the goal is a luminosity of around 1 × 1036 cm–2s–1, approximately 60 times as high as achieved at present B factories.

The conference was extremely lively, and most goals of the workshop, such as promoting co-operation and a fruitful exchange of ideas among theoreticians and experimentalists, were fulfilled. Up to now, the data agrees globally with the CKM picture, but there are also hints of discrepancies, which if confirmed could signify new physics. With the advent of the new machines, it will be feas-ible to investigate possible flavour structure and new sources of CP violation beyond the Standard Model through studies of flavour processes. Heavy flavour, and therefore physics, continues to play a fundamental role in particle physics and has an exciting future.